“I’ve known of Chinese cooks, out on the big ranches in Eastern Oregon, that, when full of hop or bad whiskey, would chase everybody with a big butcher knife that came near their kitchens.”

This is what pioneer A.J. Veazie recalled about Oregon life in the 1800s.

Not all Chinese cooks wielded big butcher knives—in fact, most were pretty quiet and kept to themselves. Throughout the 19th century the Chinese lived in their own communities, called China Town or Hop Town, in most cities.

The phrase “Chinese restaurants” means something different today than it did in the late 19th century. Today it means a restaurant where Chinese cuisine is served. Back then it usually described restaurants run by Chinese owners who served mostly Victorian fare.

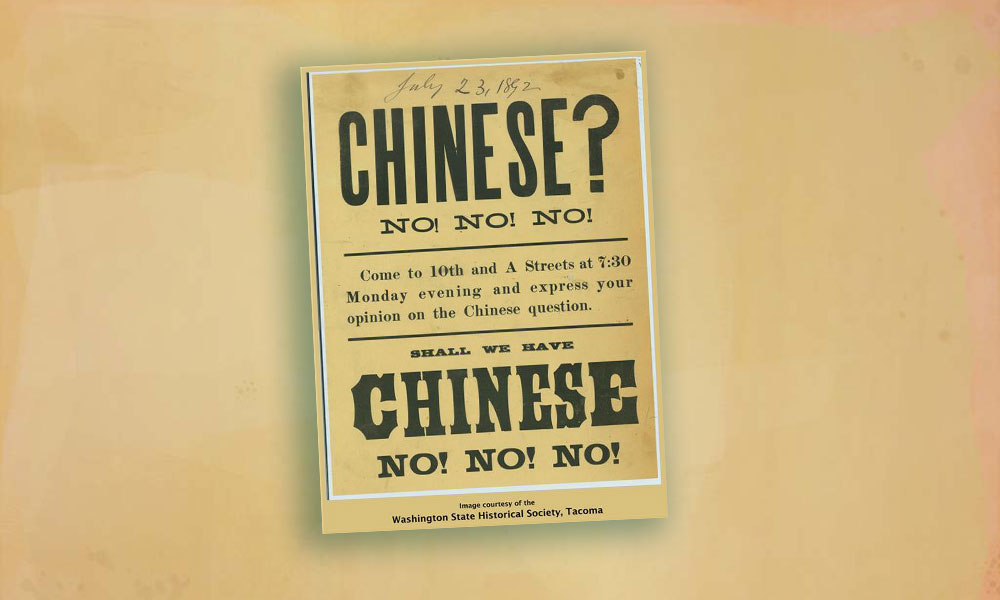

By 1883, the anti-Chinese movement was gaining speed and anything Chinese became taboo. Chinese workers were fired. Customers patronizing Chinese businesses were scorned. Businesses who failed to fire their Chinese help also felt the heat.

The Omaha Daily Bee reported in 1891 that a movement in Butte, Montana, to carry on a war against Chinese restaurants was being pursued. “A meeting will be held soon of the proprietors of white labor restaurants. It is understood that the Miners’ Union has shown much interest in the movement and will help it along.” The next year they passed a law that fined anyone who visited a Chinese business in town.

Even Los Angeles, California, dealt with the issue as late as 1896: “Gradually the Asiatics had been making inroads upon the white restaurateurs of this city until the proprietors of the latter had become alarmed. Many cooks and waiters were walking the streets, unable to obtain employment.”

By the late 1890s, though, Chinese restaurants, serving Chinese food, began to gain popularity. In 1899, the Commercial Hotel in Taylor, Texas, opened a first-class Chinese restaurant, advertising it as, “Everything is A-1 and will be kept so. Give it a trial.”

For the main meals, the chefs cooked with smoked chicken, duck and pigeons. Dried shrimp, prawns, oysters, clams and sardines were also prepared in meals. Specialty dishes included Bird’s Nest soup, Shark Fin soup, Chop Suey and Yet Quo Mein. (In 1892, the San Francisco Call reported that the city’s Chinese restaurants were importing bird’s nests from China. This was done to make their native Bird’s Nest soup.)

Even newspapers, like the Iowa Recorder in 1902, acknowledged Chinese food and its popularity. “For those who like or who think they would like the famous Chinese dish, chop suey, use the following recipe, which any intelligent housewife can follow….”

Chop Suey

1 lb. pork cut into thin strips

4 T. olive oil

½ oz. fresh ginger, diced

2 stalks of celery, sliced very thin

1 cup fresh mushrooms, sliced thin

1 cup bean sprouts

½ cup boiling water

1 T. cider vinegar

1 tsp. Worcestershire

½ tsp. each salt, black pepper and

red pepper

2 tsp. cornstarch dissolved in 2 tsp. cold water

Dash of cloves and cinnamon

Add two tablespoons of the olive oil to a frying pan or wok. Heat over medium heat and sauté the pork just until the pink disappears. Remove pork and set aside.

Add the remaining olive oil and sauté the ginger, celery, mushrooms and sprouts until tender; about 10 minutes.

Next, add the boiling water, vinegar, Worcestershire sauce and the salt and peppers. Cook for two minutes. Stir in the pork, cornstarch and spices. Continue to cook until thickened. Serve with rice and soy sauce.

***

Note: The original recipe also called for two chicken livers and two chicken gizzards, which could be sautéed with the pork.

—Iowa Recorder, 1902