The triumph of the TV miniseries Lonesome Dove is such that to once again name the awards and repeat the ratings and draw quotes from the universal accolades doesn’t quite do it justice.

At the risk of possibly underselling it, which would likely seem absurd to readers of True West, people who love great Westerns, fantastic once-in-a-lifetime performances by some of our finest actors and brilliant storytelling in the service of an eight-hour epic of the American West, Lonesome Dove is in a class by itself, and will likely remain so.

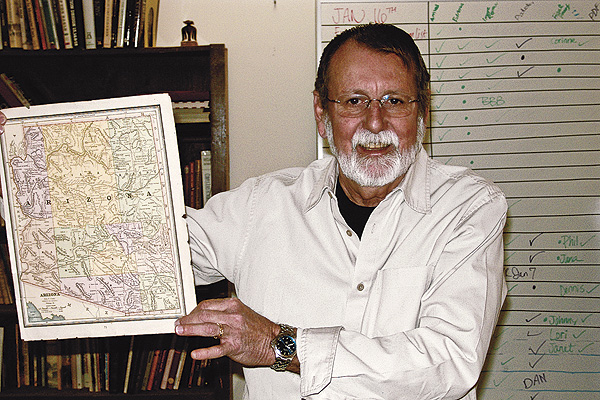

The uncommonly good-natured filmmaker Simon Wincer will tell you how lucky he was to have been given the assignment of directing Lonesome Dove, and how not a day in his life passes by that he ever forgets what it meant and continues to mean to him. Lonesome Dove was as singular an event for him as it was for the audiences who locked down into place in front of their televisions on those cold February nights.

True West: Despite Lonesome Dove’s budget constraints, casting snafus and weather problems, the series sailed to glory as if blessed.

Simon Wincer: The first few days I don’t think we even left the office where we started in Austin, Texas, ’cause it just rained and rained and rained and rained. We eventually got going, but two days [behind]; it ended up an 88-day schedule, which is 22 days per movie, a very short schedule for something as epic as Lonesome Dove….

Somehow we got it. We had such a great cast. Good material attracts good people, as simple as that, really. Everybody wanted to be in it and be a part of it because the book was so great and was so beautifully adapted by Bill [Wittliff].

How did you land the project?

I grew up in TV, and I’d done quite a few big features by that time as well. What they were looking for, I guess, was somebody who could shoot a TV schedule but with a feature background. I sort of fit the bill I suppose….

I had just finished The Lighthorsemen [1987], a film that I also produced with a partner. It was a massive undertaking. One scene involved 800 mounted riders in a charge.

I sort of fit all the boxes, if you like. And I’d done a couple of quite successful things for CBS: The Last Frontier [1986], another called Bluegrass [1988]….

I guess I was the lucky one who got the gig, ’cause everyone wanted to direct Lonesome Dove, obviously.

So there was competition?

The book had won the Pulitzer Prize, and everyone who read the book just loved it. And there was this great adaptation floating around, so a lot of other directors wanted to direct it.

I didn’t realize it so much at the time because, you know, I was a bit younger, but I would have done anything to get it. (Although I didn’t have to fight as hard as I would these days to get a similar job….)

I remember saying to my wife, “This is one of those jobs that comes along once in a lifetime. I cannot say no to this.”

After directing The Lighthorsemen, how did you feel about another three months of critters and cowpies?

[Laughs] Well, I happen to revel in it, because I’ve been around horses all my life. I have a farm, and I ride every day of my life when I’m not working.

I’m actually in Queensland doing a live arena show called the Australian Outback Spectacular—I guess you have something similar called the Dixie Stampede. It’s a fantastic show that’s been very successful. I’m doing a new version of that which integrates live arena action with high-definition photography on a screen. It involves lots of horses and cattle and sheep and dogs and helicopters and everything else that’s fun.

Where in Australia do you live?

I live on a farm just outside Melbourne. You can see a bit of it—that’s where they interviewed me, sitting outside, for the recent Lonesome Dove DVD package.

How similar is Australia’s Wild West to America’s?

[Australia’s] gold rush came around 1854, so it was a similar sort of thing with people, flooding to the country and outback towns, from all over the world, in the rush to find gold. It was a real melting pot. Not quite as wild as the American West, I don’t think, but nonetheless guns were just stuck in belts and there were rough times and a lot of conflict with the police. We were still emerging from the days when we were a convict settlement.

Did your interest in Australia’s history inspire interest in ours?

My love for the American West really came from the Saturday afternoon serials—Hopalong Cassidy. I grew up in the fifties and sixties…. I’d been around horses all my life, and I loved the bush [rural region] too. It was a kind of natural progression.

Did your country upbringing influence you as a filmmaker?

It’s different from some American directors who might have grown up in an urban environment. You have a whole different set of eyes, because you learn to appreciate the life and the weather, or the way weather affects landscapes and life on the land…. I think that’s why, in my films, landscape plays such an important part. It’s just another character to me, because it governs everything we do. That’s what I tried to capture in Lonesome Dove—in all my movies—is the relationship of the characters to their environment.

That’s come about because of an appreciation for the weather. Every morning, the first thing I do is look out to see if it’s going to rain, you know? [Laughs.] ’Cause we’re always wanting rain at our farm.

Movies, not TV, is where people saw Westerns set in the great outdoors.

Yeah, yeah, ’cause the television Westerns were mostly full of in-town scenes shot on backlots. You never really got to see the big skies until you went to the movies and saw John Ford pictures and Monument Valley.

Did you shoot any of Lonesome Dove on a Los Angeles backlot?

No, no, no. Our first two weeks we shot in Austin, Texas. In fact, the very first day of shooting was the whiskey boat with Elmira [Glenne Headly]. That was a morning shooting. In the afternoon we filmed when Roscoe [Barry Corbin] picks up the little girl [Janey, played by Nina Siemaszko], and she hitches a ride on the back to help him find July Johnson [Chris Cooper]. Our first two weeks were in Austin. Then we moved down to Del Rio for about six weeks, and Brackettville, and all that down there. Then we moved from Texas up to New Mexico, up in the mountains to do all the Montana stuff. Near Taos. Then the last six weeks were in Santa Fe and all around Santa Fe.

Was Santa Fe and Taos the farthest north you got?

Yeah. Honestly, the mountains around Santa Fe and Taos are so great, and we couldn’t afford to go to Montana. Around Taos we got Clara’s house and all that sort of stuff and a lot of the town stuff. So we were able to get all the contrast and the feeling of the journey just between those two major areas.

Didn’t you shoot Comanche Moon in Taos-Santa Fe as well?

Yes, except for going back for a bit to Del Rio and all around San Antonio. We shot some in Las Vegas [New Mexico].

I think of Las Vegas as the original grand central station for many of the most famous Western characters.

Oh, the magnificent old railway buildings! That’s where they shot No Country for Old Men. Literally, as soon as you leave Las Vegas, you get into the big open plains, endless, endless landscape, like the Texas plains. Larry [McMurtry] was thrilled when he saw that location ’cause he said, “That’s what I want, THAT’s what I want, those big sweeping plains.”

Before I watched Comanche Moon, I wondered how you were going to manage Val Kilmer’s character after he had his eyelids removed.

Oh yeah. Well, a lot of that stuff would have been too brutal, we thought, for television. It’s interesting ’cause Comanche Moon was obviously written during a very dark period of Larry’s life. I think he’d just had heart surgery. It’s a much, much darker piece than Lonesome Dove.

It really is a requiem for the Comanche nation, the end of the Comanches. I think it’s a wonderful piece. And I thought that Karl Urban and Steve Zahn were wonderful as Call and Gus.

Was it fun to revisit those characters with new actors?

It was, and particularly with Steve, where it was a case of not wanting to mimic what Bobby Duvall had done, but he did want to honor it. I thought he did it really well. It was a lot of fun actually. And those were big shoes to fill.

Zahn does share qualities with Duvall that make Gus such a charming rascal

Absolutely. I think he’s a wonderful actor. Just great. An absolute joy to work with. And he’s a terrific horseman—he lives on a horse farm in Kentucky. I’d work with him again tomorrow. He’s desperate to do another Western.

I hear you’re making Michael Blake’s sequel to Dances With Wolves, The Holy Road.

Holy Road, in a way, is another Comanche Moon, but it’s told from the Comanche’s point of view. It’s very, very powerful. It’s a wonderful project, but it’s a tough time for financing movies. It’s epic and dark, and a really powerful adventure story.

Charm is a scarce commodity in most Westerns, yet it shows up in Lonesome Dove, Quigley Down Under and many of your other pictures.

All my movies have a very strong emotional through line. Some people, I go for the jugular when it comes to the emotion. My wife complains, “Your films always make me cry!” [Laughs.]

I’m not into, you know, dark, dark, dark. I think we’re assaulted by so many unwatchable movies these days because the people are just so unattractive, unappealing. You’ve gotta care about somebody if you’re going to spend two hours with them on screen. That’s what I feel anyway. I’m sick of being assaulted by unsavory characters doing awful things to people. If you’re going to feel for somebody, yes, you can hate them or whatever, but I still like to try to show both sides.

The dark material in your Lonesome Dove is tempered by Gus’s good nature.

And that’s very much the strength of the book. Everybody falls in love with Gus because he loves life, loves to party, he drinks and goes around screwing and having a great time, you know? All his doors and windows are wide open.

Call is the total opposite. Duvall was approached to play Call, and he said, “I don’t want to play that character. I’ve played that character. I want to play Gus.” Understandably.

He’s played Gus twice since then, in essence.

That’s true. Absolutely. He has indeed. You’re thinking of the Kevin Costner Western, Open Range.

And Broken Trail.

He really pulled it off. He was fantastic.

During my interviews with Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones, I couldn’t help seeing a lot of Gus and Call in the both of them.

Well, it was a real stretch for Tommy. Firstly because when he was cast, the network wanted a television star, and we had a real bloody battle. As we were casting Anjelica [Huston], Diane Lane, Robert Duvall, they kept saying, “This is CBS, not PBS.” [Laughs.]

Tommy Lee, his career had taken a bit of a dive bomb when he was cast. It was a real stretch for both of them, age-wise. They both spent a lot of time each day in the makeup chair, but boy did they pull it off!

Tommy Lee is incredibly erudite, very bright, roomed with Al Gore, played football at Harvard. Because of his accent, people think Tommy Lee is a hick. But he’s probably got the most awesome vocabulary of anybody on earth. He’s an incredibly intelligent man. And he brings all that to the table as an actor….

We hit it off right from the start because we share a love of horses. I showed him The Lighthorsemen just before we started, and he knew that I knew how to shoot horses and people on horses, and stuff like that. We’ve kept in touch over the years whenever we can.

Do you agree that Lonesome Dove closed the door on tired Westerns, movies and TV alike?

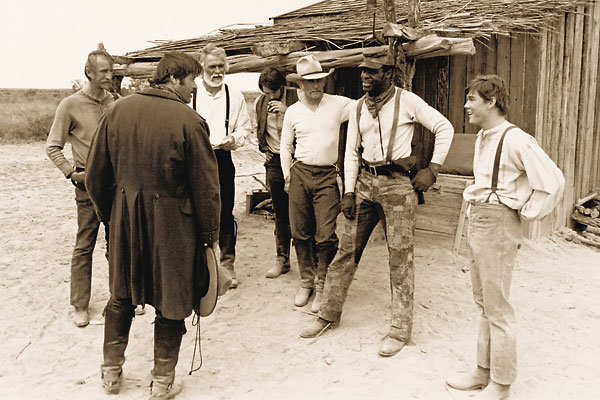

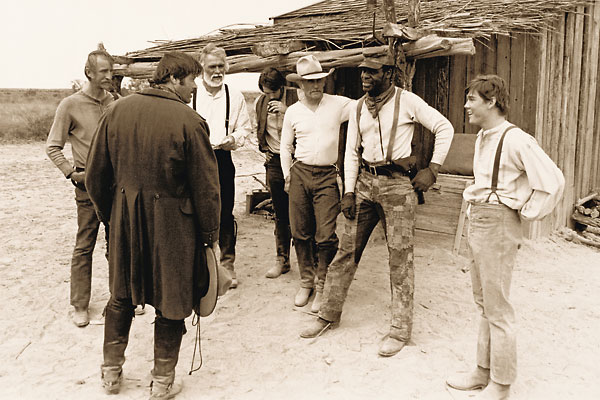

With Lonesome Dove, one of the things we—Bill Wittliff and Cary White, the production designer, and myself—tried to do, we went back to the history books. We went for the reality. We went for the dust and the dirt and the flies, and the wind and the rain and the blowing hair.

It was a whole sort of new look just in terms of the feel of it, from the production point of view. The Western had become very bastardized, through television and people wearing silly hats and little waistcoats and jeans. It had all slowly sort of eroded.

All of a sudden, here were these real characters. They were covered in mud. They had cattle s— on their boots. I wouldn’t let people pick the s— up off the streets. I said “No, no, no. There’s no one to do that. They wouldn’t have been doing that….”

So it had that slightly gritty look about it, and that was important to me. Again, it’s all about smell and atmosphere, you know? It was important to capture.

Sex also separated Lonesome Dove from its TV predecessors.

Yeah, it was all there in the book. We were able to push the boundaries as far as we were allowed, but it was all done pretty tastefully. “How about a poke?” People still react to that. That’s very Australian. “Did you have a good poke last night?” we refer to it here.

It’s all done with a twinkle, and that was the beauty of Gus’s character, he always had a twinkle in his eye. He just loved life. People latched on to that. By the time night four came along, which is still one of the highest-rated dramas ever—the last night rated 54! It’s staggering!—restaurants went empty because everyone stayed home to watch Gus die.

I should tell you one story…. Bill [Wittliff], Dyson Lovell, Suzanne De Passe and I went to CBS, on Beverly Boulevard there, and sat in the boardroom, right next to reception. In clomped all the various executives for a 10 a.m. screening. We were going to show them the first two hours, and then we were going to have lunch, and then come back and show them the next two hours. Then two days later we were going to show them the last four hours….

It starts, not a word is said. The lights come up, end of night one, and not a word is uttered. Not a word. We all go off to lunch, thinking “Holy s—! What’s this about?” Not having had even one reaction from anybody except, “Thank you very much.”

We come back at 2:00. Everybody clomps back in again, and we all sit down. I go to switch on the next two hours and one of the executives says, “Oh, I just want to say something.”

Then he began to say how proud they were of the first two hours they’d seen. What a fantastic job we’d all done. What brilliant television it was. And if no one even watched it, they wouldn’t care, because it was so bloody good. They were just thrilled with it.

The four of us breathed a sigh of relief…. Two days later they asked, “How’s the running time?” We said, “We wanted to talk to you about that. Do you want a nine-hour miniseries?” [Laughs.]

At that time the miniseries was dead, the Western was dead. They’d had a disaster with, I think it was, War and Remembrance, which had been pulled before they’d finished screening the series. So this was a huge risk.

When Lonesome Dove aired, they still hadn’t sold all the advertising. Yet within a few months, it aired a second time and then a third time on network television, which hadn’t ever happened.

So you cut out an hour of footage from the miniseries that aired on TV?

There’s a wonderful scene where Gus is in search of Lorena. He’s going across the open plains, and there’s an old man collecting buffalo bones and piling them into pyramids. An old guy he’d once had a shoot-out with. They’re yelling at each other as he rides past.

Great stuff with the cowboys when they first taste Po Campo’s cooking…. A lot of stuff with Call and the hell bitch, when hell bitch is continually throwing him off at the most inappropriate times.

Not stuff you miss, but it would have been lovely to be able to reissue it all in a new edition. It would have sold like hotcakes. Finding the stuff would be hard, because I think the company that made the film has gone under, but it has been talked about.

Who is the most underrated performer in Lonesome Dove?

Robert Urich. There’s a moment, early on, when they’re sitting around the breakfast table, and he tells them how he accidentally shot the sheriff through the wall. He actually breaks out laughing in the middle of that story. It was the most brilliant moment because that was one of his early scenes with Bobby [Duvall] and Tommy Lee and Danny Glover. I watched them, thinking, “Boy oh boy, this guy can act,” because Robert was out of television and they were all movie actors. All of a sudden, subconsciously, there was a challenge almost thrown down because it was such a brilliant moment. They thought “Whoa, this guy is really with his character.”

The hanging scene, when they hang Jake [Urich], I remember it very clearly because we shot it on a Good Friday. That moment between him and Gus, just before Gus whacks the horse on the ass, and the incredible reaction from Bobby Duvall after. By the time that happens, you’ve spent so much time with the characters in the course of the series, you really share their grief.

I’ve always thought that Gus and Call make a classic comedy duo.

Absolutely, but I think of it as whimsy more so than comedy. Their chemistry together is wonderful because they’re always bickering. Bickering characters that endear you. And conflict is the basis of all good drama. That’s what it’s about.