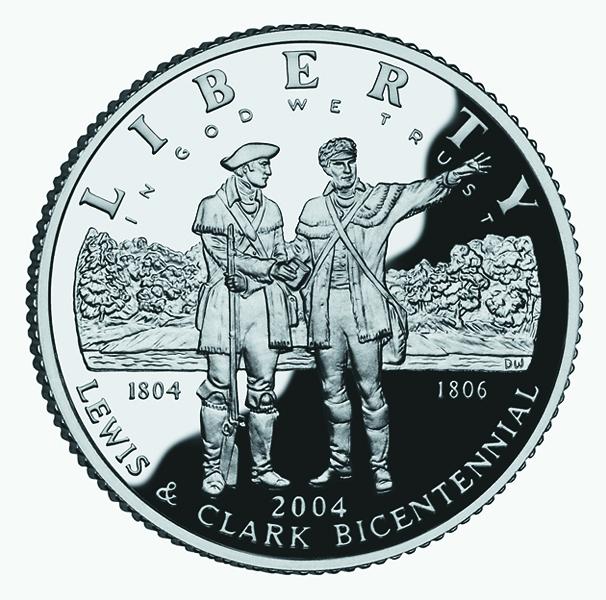

The plan had been set in 1805 when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark noted where the Yellowstone River joined the Missouri and later gazed upon the river farther west and to the north, which they named the Marias.

The plan had been set in 1805 when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark noted where the Yellowstone River joined the Missouri and later gazed upon the river farther west and to the north, which they named the Marias.

The explorers had successfully crossed the Continental Divide, made friendly contact with the Nez Perces and later with the Chinook Indians, had seen the Pacific Ocean and spent the winter at Oregon’s Fort Clatsop before turning east once again. They stopped to rest with the Nez Perces before crossing Lolo Pass (at the present-day Montana/Idaho border) and dropping into the northern Bitterroot Valley to the place they called Travelers’ Rest from their two-day stay the previous fall.

Now it was the summer of 1806 and they would divide the Corps of Discovery, not for a few days, as they had occasionally done on the westbound journey to allow slight detours and explorations, but instead for weeks. Lewis would take a portion of the expedition members, travel northeast, find the Marias and follow it, searching for a natural boundary to delineate the American territory. Clark and 13 companions would travel south, retrieve cached supplies and then go to Three Forks. There, some of the men would take a portion of the supplies on to Lewis and reunite with him while Clark and the others would find and follow the Yellowstone River. The parties would regroup at the confluence of the Yellowstone with the Missouri.

The captains parted in early July. Lewis recorded in his journal, “I took leave of my worthy friend and com panion, Captain Clark, and the party that accompanied him. I could not avoid feeling much concern on this oc-casion, although I hoped this separation was only momentary.”

Clark wrote on July 3, 1806: “We collected our horses, and after breakfast I took my leave of Captain Lewis and the Indians, and at 8 A.M. set out with [the] men, interpreter Charbonneau and his wife and child … with fifty horses.”

Although delayed because the party’s horses were scattered, by July 8, Clark and his companions had traversed the Bitterroot Valley, crossed the Big Hole and reached their campsite of the previous August 17, where they had buried their canoes and cached supplies.

“I found every article safe, except a little damp. I gave to each man who used tobacco about two feet off a part of a roll, took one third of the balance myself,” Clark wrote. He organized some supplies, including part of the tobacco, to be taken downstream by a few men and delivered to Capt. Lewis.

Clark’s men repaired the canoes, loaded their supplies and set off. Some traveled on the river, while others took horses overland.

By July 13, Clark was at Three Forks and Sgt. Nathaniel Pryor, who had traveled overland with some men and the horses, joined him there with the carcasses of six deer and a white bear (grizzly). After a short rest and meal, the party split again. Sergeant John Ordway and some men would proceed by land, taking supplies to reconnoiter with Lewis at the mouth of the Marias River.

Clark, who would turn southeast and strike the Yellowstone, noted in his journal, “My party now consists of the following party, viz., Sergeant N. Pryor, Joe Shields, G. Shannon, William Bratton, Labiche, Windsor, H. Hall, Gibson, Interpreter Charbonneau, his wife and child, and my man York—with 49 horses and a colt.”

From Sacagawea, he had learned of “A gap in the mountain more south.” Thus Clark headed toward what would eventually be called Bozeman Pass, named for John Bozeman who pioneered a trail to Montana’s goldfields in 1864.

Following Clark through Montana

I begin following Clark’s route in Lolo, Montana, site of Travelers’ Rest, arriving there on a summer evening just as a wedding is concluding. I decline refreshments at the reception and, instead, walk the area where the Corps of Discovery likely spent many days.

From Lolo, my route on U.S. Highway 93 is south through the Bitterroot Valley toward the Big Hole, but I remain on Highway 93 and detour from Clark’s route to Salmon, Idaho, where the new Sacajawea Center opened in 2005. Located at the south edge of town on what was a ranch, the 71-acre outdoor park has interpretive exhibits and a walking path that takes you down to the Salmon River. The path’s signs largely relate to the Agaiduka or Lemhi Shoshonis—Sacagawea’s people. In one area, a camp has been re-created and living history interpreters share information about life in the early 1800s and present educational programs for children and adults.

From Salmon, I backtrack on Highway 93, returning to Montana and then turning south on Highway 43 to the Big Hole where I take Highway 278 to Dillon. From there, I follow Highway 41 and the Jefferson River to I-90 and Three Forks. The Sacajawea Hotel is a good place for a meal or an overnight stay before visiting Three Forks, near the Missouri Headwaters State Park, and then driving east through Gallatin Valley toward Bozeman.

This is country Clark saw in mid-July of 1806. Sacagawea was his main source of information about the area. Clark wrote on July 14 that she “informed me that there was a large road passing through the upper part of this low plain from Madison River through the gap, which I was steering my course to.” Clark saw “elk, deer, and antelopes, and a great deal of old signs of buffalo. Their roads are in every direction. The Indian woman informs me that a few years ago buffalo were very plenty in those plains and valleys.”

As Clark’s party proceeded through the Gallatin Valley, called “Valley of the Flowers” by the Blackfeet, Crow, Salish and Shoshoni Indians, Clark recorded the scenery and the wildlife. On July 15, 1806, he wrote, “I saw two black bear on the side of the mountains this morning. Several gangs of elk, from 100 to 200 in a gang, on the river. Great numbers of antelopes.” On July 16, he “Saw a large gang of about 200 elk and nearly as many antelope; also two white or gray bears in the plains.”

Bozeman today is one of Montana’s largest cities, home to Montana State University and the Museum of the Rockies, with its displays related to early pioneers and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. You’ll find good shopping, and the Baxter Hotel serves a fine meal downtown.

By the time Clark had crossed what became Bozeman Pass, his horses had hooves so sore, some could barely walk. He cut pieces of leather and wrapped them around their hooves to ease their pain. He continued traveling until he and his men finally reached the Yellowstone River at present-day Livingston. Clark then instructed some of his men to proceed with the horses, while the remainder of his group built canoes for river travel.

After searching several miles of river for suitable trees, Clark was “determined to have two canoes made out of the largest of those trees and lash them together, which will cause them to be sturdy and fully sufficient to take my small party and self with what little baggage we have down this river.”

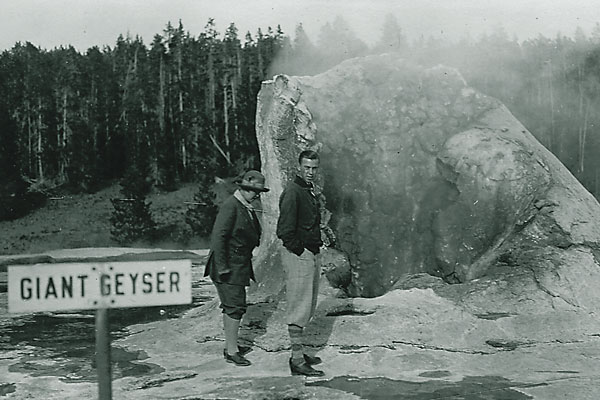

Although Clark missed seeing the area that would become Yellowstone National Park, a traveler today ought to take a side trip through the Paradise Valley and enter the park’s northern entrance, 40 miles south of Livingston. Another good reason for this trail diversion is to partake in the extensive breakfast buffet or indulge in a swim/soak at Chico Hot Springs. Had Clark known about the soothing waters of Chico, he almost certainly would have gone there himself.

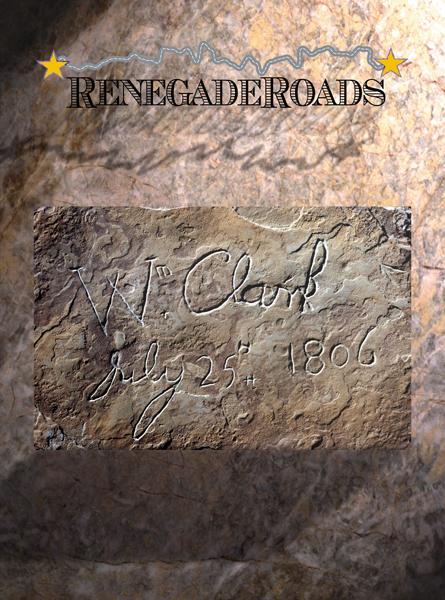

But his trip predated the development of Yellowstone National Park by nearly seven decades and Chico by even more, so he instead launched his canoes into the Yellowstone River and traveled rapidly downstream. On July 25, Clark reached a “remarkable rock situated in an extensive bottom on the star board side of the river and 250 paces from it.”

After climbing the rock where he saw two piles of stones made by Indians, he had a “most extensive view in every direction.” He wrote, “This rock, which I shall call Pompey’s Tower, is 200 feet high and 400 paces in circumference, and only accessible on one side, which is from the N.E., the other parts of it being a perpendicular cliff of lightish-colored gritty rock. The natives have engraved on the face of this rock the figures of animals, &c., near which I marked my name and the day of the month and year.”

Clark’s decision to carve his name on the rock he named for Jean Baptiste Charbonneau—the “little dancing boy” who had traveled with his mother Sacagawea and father Toussaint Charbonneau, and worked his way into the hearts of the men of the Corps—became more significant as time passed. Located off I-94 east of Billings, the rock is the only tangible evidence of the Corps of Discovery’s expedition.

Leaving Pompey’s Tower (now called Pompey’s Pillar National Monument) and traveling northeast on the Yellowstone, Clark’s party made good time in the final leg of their trip independent of Lewis. They had to halt for great herds (he called them “gangs”) of buffalo to cross the river, and they had to fight off grizzly bears that rushed their boats, but they reached the confluence of the Yellowstone with the Missouri, where they found the “mosquitoes excessively troublesome.”

The story of these two rivers, as well as exhibits on Lewis and Clark, can be found at the new (opened in August 2003) Missouri-Yellowstone Confluence Interpretive Center in Williston, North Dakota. To get there from Pompey’s Tower, stay on Highway 94, take exit 213 toward Sidney, turn left at Montana Highway 16 and left onto U.S. 85 North. Part of the Fort Buford State Historic Site, the center is featuring Vern Erickson’s art depicting the Corps’ expedition in North Dakota through April 23. He’s also a featured artist at the North Dakota Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center in Washburn.

When Clark decided to push on down river, he left a note for Capt. Lewis. He wrote in his journal on August 4 that he shared his plans in this note to Lewis “and tied it to a pole which I had stuck up in the point. At 5 p.m., set out and proceeded on down to the second point.”

At noon, eight days later, “Captain Lewis hove in sight.” He had encountered Indians on the Marias, leading to a dispute over guns that left one of the Indians dead. Just the previous day, Lewis had been shot in the butt by Pierre Cruzette, while the two were out hunting elk; the fiddle player apparently mistook Lewis for an animal.

Reunited, the Corps of Discovery set off on their final leg of the journey home.

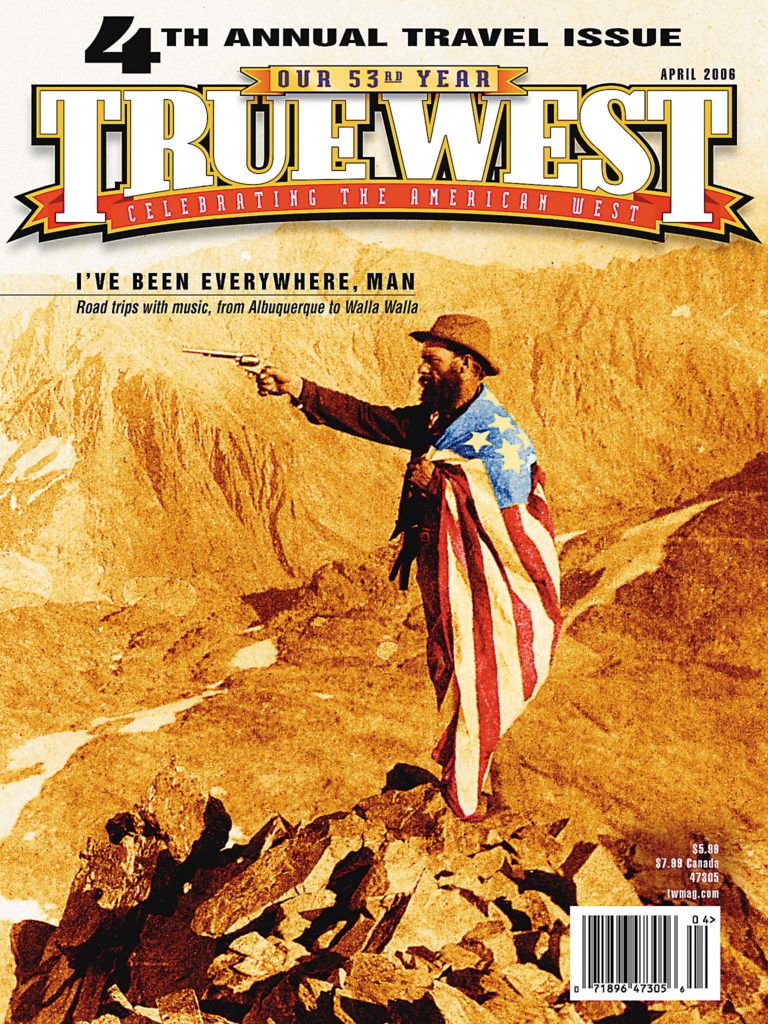

Photo Gallery

– By Candy Moulton –

– Courtesy U.S. Mint –

– All photos by Donnie Sexton / Travel montana except otherwise noted –

– William Clark courtesy Missouri Historical Society –