— Photos Courtesy Rosebrook Family Collection —

Prescott, Arizona, has been a center of Cowboy Culture since 1888, when civic-minded merchants first posted cash prizes for a cowboy tournament, giving birth to Prescott Frontier Days – The World’s Oldest Rodeo. The celebration predates the familiar use of the word “rodeo,” Spanish for “to roundup.” It was not applied to cowboy contests until 1916 and not in Prescott until 1924.

Prescott’s links to Hollywood can be traced to 1909, when a rodeo cowboy and movie bit-player named Tom Mix first entered the rodeo, returning in 1913, by then an international movie star, to win first prize in steer-riding and bulldogging. He settled in Prescott, as Selig-Polyscope Company Producer Col. Selig bought him the Diamond S Ranch as both home and studio, where over the next year and a half he made a Western a week—about 75 movies in all.

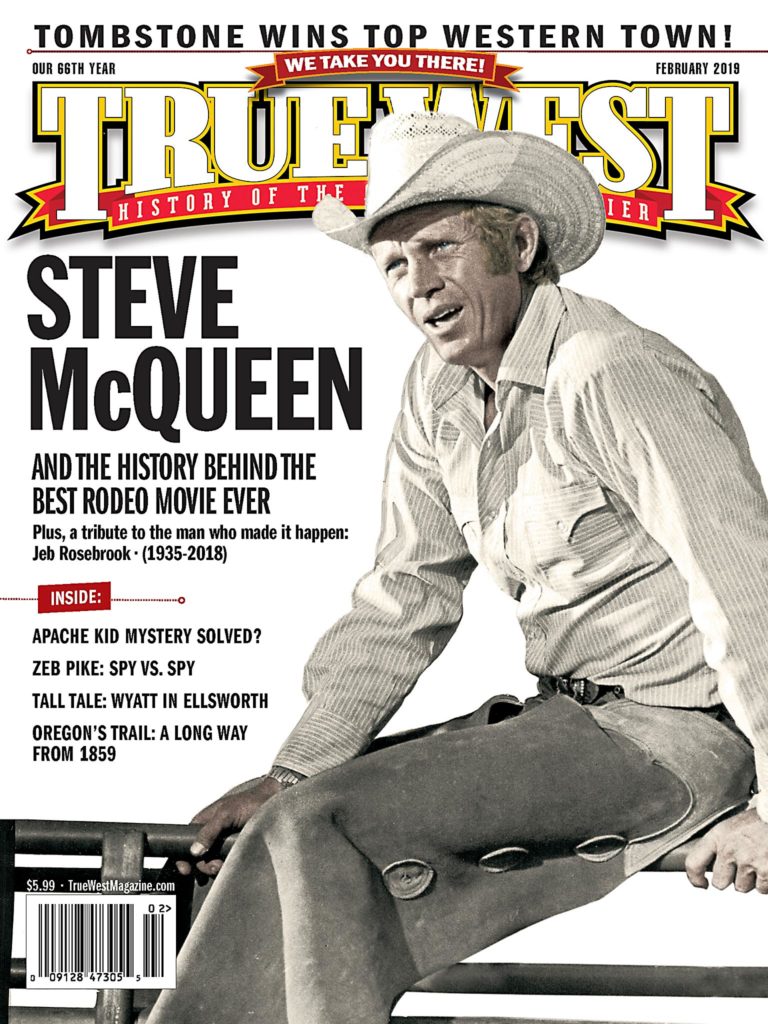

Prescott lapsed into cinematic slumber until 1940, when the town began hosting a number of B-Western productions, variously starring Tex Ritter, Col. Tim McCoy, Buck Jones and Tom Keene. She dozed again until 1969, when her beauty proved an effective backdrop for angst and rebellion, beginning with Billy Jack and later Bless the Beasts and Children, both released in 1971. While other notable movies have since been shot in Prescott, including 1978’s Comes a Horseman, and a couple starring Sam Elliot, there is only one film whose outdoor screening has become a tradition of Prescott Frontier Days, and that is perhaps the greatest of rodeo films, 1972’s Junior Bonner, which not only was set there and shot there, but tells a story that was born there.

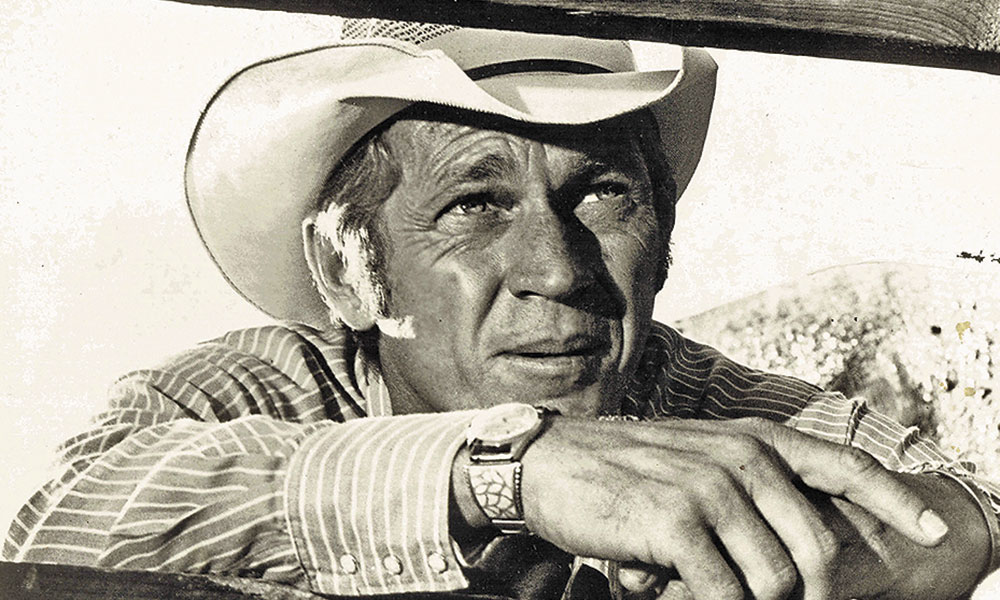

It’s the story of bullrider Junior Bonner (Steve McQueen), who has come home for the rodeo, swings by the house of his father, Ace Bonner (Robert Preston), to find him gone. The property is being bulldozed for a housing development being built by his brother, Curly Bonner (Joe Don Baker). Director Sam Peckinpah was only six pages into Jeb Rosebrook’s script when he decided to make the film. Sam’s own mother was selling off his father’s ranch for development, and the story hit close to home.

When Rosebrook first met his film’s soon-to-be-star Steve McQueen, he listened mesmerized as the coolest man and highest-paid actor in Hollywood told him and producer Joe Wizan his many ideas about the script. Finally, indicating Rosebrook, McQueen asked Wizan, “Doesn’t he take notes?”

Wizan shook his head with confidence. “Jeb always remembers.”

Fortunately, Wizan spoke the truth, because Junior Bonner: The Making of a Classic with Steve McQueen and Sam Peckinpah in the Summer of 1971, is a book that no one but Rosebrook could have written. While there have been many fine “The Making of…” movie books, most are products of reverse engineering, with the author trying to trace the making of a classic years after the fact, generally relying on ancient press releases, the often self-serving memories of participants and guesswork. With Bonner, Rosebrook, writing with his son Stuart Rosebrook, was there not only from the story’s conception, but he lived the childhood that created memories that triggered Bonner, a movie considered among the best work of Peckinpah and McQueen.