— Edward S. Curtis, Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Negative no. 160459 —

No American battle (except perhaps Gettysburg) has been the subject of so many books and movies as the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn in Montana Territory—and for clear reason. The Lakota Sioux and their Northern Cheyenne allies, guided by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, wiped out Lt. Col. George A. Custer and five companies of the U.S. 7th Cavalry. The news shocked the nation as it celebrated its 100th birthday. All told, 268 officers, enlisted men, scouts and civilians were killed or died of their wounds in the greatest victory of American Indians over the U.S. Army in the period after the Civil War.

“Custer’s Last Stand” became a legend in its own time; and no such conflict on our soil, arguably not even Gettysburg, has been the subject of so much debate and second-guessing—as to who and what was responsible for the disaster on that bloody Sunday in June 1876. Great controversy arose from that mighty afternoon because the Army had suffered such a humiliating defeat and because Custer had been a well-known, controversial figure with a reputation for reckless ambition and insubordination. If the legend of the Western frontier has shaped much of the nation’s culture and values, one might argue that the legend of Custer and his perpetual Last Stand has, in turn, so shaped our image of the so-called “winning of the West.”

Curtis Captivated by Little Big Horn

— Edward S. Curtis, Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Negative no. 160467 —

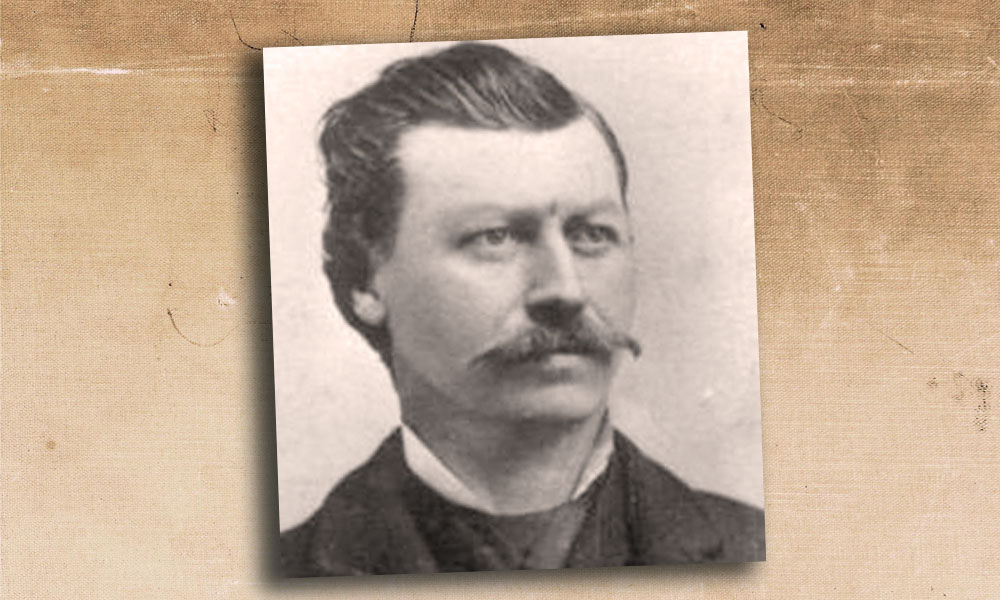

Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) was among those captivated by the story of the Little Big Horn. As perhaps the nation’s foremost photographer of American Indians, he was devoted to reflecting the essence of traditional American Indian culture before it disappeared. “Chasing down these images would consume Curtis for decades,” Wayne Curtis notes, “and resulted in tens of thousands of prints capturing a life that had largely vanished by the next generation.” This monumental effort culminated in the twenty volumes of The North American Indian. [See True West, July 2018.]

While researching his volume on the Sioux, Curtis became aware of the challenges of weaving a coherent picture of the Little Big Horn from the Native American perspective, especially the action on Custer’s battlefield, where the five cavalry companies had perished. “Accounts of the affair by Sioux participants I found confusing,” he concluded. “Indian encounters are not a matter of concerted action but individuals, largely every man for himself. I covered the ground of the Custer final encounter with a number of able Sioux. They could vividly tell of their own actions in the affairs, but could give no comprehensive account of the action as a whole.” Dissatisfied with his Lakota interviews, Curtis largely depended on three of the Crow scouts who had guided Custer’s column “in pursuit of the Indians” believed to be on the Little Big Horn River.

The Crow Scouts

— Edward S. Curtis, Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Negative no. 160469 —

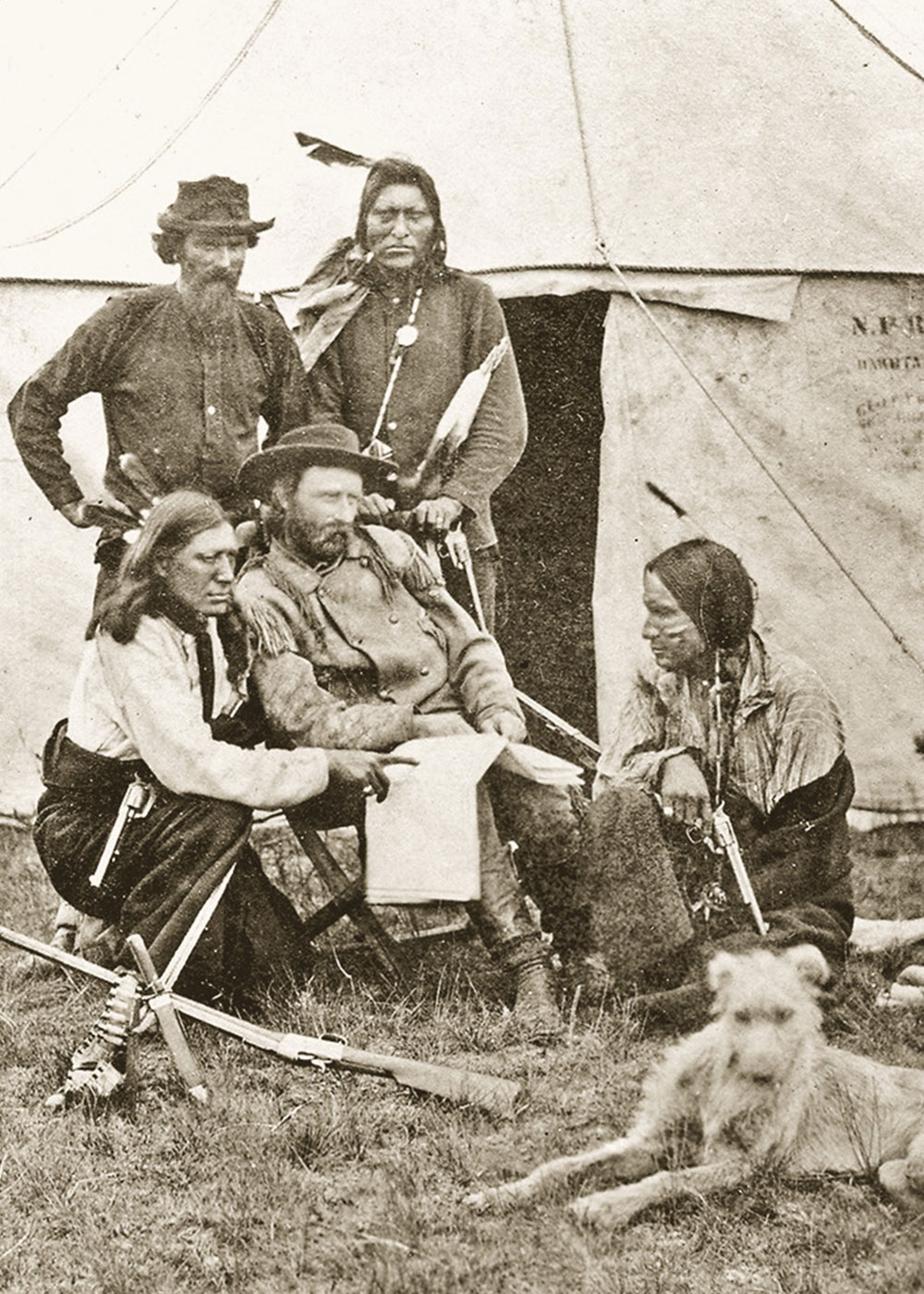

Confidence in their story seemed justified. Prior to Custer’s fatal march, six Crow scouts and the guide and interpreter Mitch Boyer were assigned to the 7th Cavalry because they knew the country so well. (Custer’s last battle, ironically, was fought on the Crow Reservation.)

Boyer, according to Col. John Gibbon, was reputed to be “next to the celebrated Jim Bridger, the best guide in the country.” Gibbon’s chief of scouts, Lt. James H. Bradley, lamented the loss of Boyer and “my six best men” because it not only left Gibbon’s command without a guide but their assignment also afforded Custer “every facility to make a successful pursuit.”

For his part Custer praised these “magnificent looking men” detailed to lead him to the Sioux. On the morning of June 25, Boyer and the scouts spotted their target in the Little Big Horn valley, 15 miles away as evidenced by the campfire smoke and the enormous horse herd that looked like “worms in the grass.” The Crows urged Custer to strike the village a day before he had intended because they warned that the Sioux had discovered his command and would escape the Army’s attempt to subdue them. The scouts clearly had a stake in the defeat of their tribal enemies.

After Custer ordered Maj. Marcus Reno’s battalion to advance because enormous dust clouds in the Little Big Horn valley apparently confirmed the flight of the Indian encampment, Boyer and four of the Crow scouts remained with the five companies under Custer’s immediate command. (Two of the Crows inadvertently joined Reno.) Following the major toward the river for only a short distance, the two Custer battalions turned to the right (north) for the bluffs that towered above the east bank of the river. The reason for this decision, and Custer’s precise route to his battlefield, has been the subject of endless controversy and speculation.

The Reno Conundrum

— Edward S Curtis, Courtesy Library of Congress —

Curtis was among the legion who have attempted to solve this mystery when he rode along this terrain in 1907 with three of the scouts: White Man Runs Him, Hairy Moccasin and Goes Ahead. They agreed to conduct the photographer on horseback along the route that Custer had followed from the observation point where the village had been located to Custer’s battlefield, duplicating the 1876 pace and pauses, noting the time between every important point to the next. “Every incident and accident,” Curtis noted, “which the scouts could recall were mentioned” as they followed in Custer’s footsteps.

Capably interpreting was Alexander B. Upshaw, a graduate of Carlisle Indian School. Conspicuously absent from the group was the fourth scout, Curley (or Curly), who had separated from his brethren at some point after Custer turned north and who might have witnessed the initial action on Custer’s battlefield. Clearly there was bad blood between Curley and the others. But that is another story.

After the scouts had traced Custer’s route along the bluffs, they led Curtis to the two high, parallel ridges known as Weir Point, where the entire village would have been visible. There White Man Runs Him made a shocking revelation—that Custer had watched Reno’s entire fight in the valley below, including the major’s chaotic retreat. The scouts also claimed that Custer had dismissed their plea to assist Reno. “It is early yet and plenty of time. Let them fight. Our time will come.”

The five cavalry companies then proceeded to their doom down a ravine toward the river. Before Custer engaged the Indians, Boyer released the three scouts (according to their versions, anyway) because they had performed their duty by leading Custer to the Sioux.

Their subsequent movements are confusing and unclear, although they told Curtis as well as others that they rode a short distance north to fire three volleys into the village before turning back. They apparently saw little or none of the action on Custer’s battlefield. Their next known appearance was on June 26 at the mouth of the Little Big Horn, where they informed Bradley’s Crow scouts that all of Custer’s men had been killed and the three men then fled. Again, this is another story for another time.

— Edward S. Curtis, Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Negative no. 160458 —

Most students of the Little Big Horn would probably agree with the Crow scouts’ version of the route taken by Custer’s command to the ford opposite the northern end of the Indian village. Be that as it may, Curtis was troubled by their claim that Custer waited on Weir Point “from 45 to 60 minutes” watching Reno’s fight. “Had he gone to the aid of Reno,” Curtis privately believed, “the Sioux would have been routed in half an hour, without doubt.” When interviewed by the New York Herald later that year, he revealed the disturbing (and to him the only) conclusion that his field trip to the battlefield had revealed. “General Custer unnecessarily sacrificed the lives of his soldiers to further his personal ends.” His opinion collided with that of Capt. Edward S. Godfrey and others—that Reno’s “panic rout from the valley” was the principal cause of the battle’s outcome because it enabled warriors to concentrate in force against Custer’s immediate command. Based on what the scouts had told him, Curtis believed that the real victim of the Little Big Horn was Reno, not Custer, and that an investigation of the battle was warranted.

Roosevelt Intervenes

— Edward S. Curtis, Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Negative no. 160453 —

Among those with whom Curtis shared this story was his friend Theodore Roosevelt. Not believing the allegation, however, the President provided no encouragement. He cautioned Curtis about the difficult challenge of writing about an event 30 years later. “Such a theory [about Custer’s delay] is wildly impossible,” he informed the photographer on April 8, 1908, and “makes Custer out [as] both a traitor and a fool.” Curtis heeded Roosevelt’s advice and that of knowledgeable Army officers to avoid the subject “for the time being” at least. “The President’s thought is that I am taking too large a responsibility on myself,” he informed retired Brig. Gen. Charles A. Woodruff, who had participated in the Little Big Horn campaign as a young lieutenant in Col. Gibbon’s command. Notwithstanding his “great interest” in the Custer fight, Curtis believed that his “work is not, primarily, a historical one, but rather a work treating of the Indian with a chapter on history to give the more important points.”

Custer’s widow represented another restraint to publishing criticism of her husband in her lifetime. (There was apparently an unspoken agreement among the 7th Cavalry’s officers who survived the battle to so refrain; however, Elizabeth Custer outlived all but one of them!) Curtis recognized the differences of opinion among Army officers “as to advisability of publishing the material [about the Crows’ story], particularly owing to the fact that Mrs. Custer is still alive.” He decided to wait until after her death.

An early draft of the Little Big Horn chapter for Volume 3 of The North American Indian had criticized Custer for “failing to follow orders,” his determination “to take the whole situation into his hands” and his division of his command. It noted that Custer had “watched much of Reno’s fight; watched until Reno’s men in retreat forded the river” to climb the bluffs. Such criticism disappeared upon the volume’s publication in 1908.

Curtis’s Conclusions

— Courtesy National Park Service, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, LIBI_00312_11106 —

Edward S. Curtis was not the only one with whom the Crow scouts talked about the Little Big Horn. Several others interviewed them, notably Plains Indian Wars researcher Walter M. Camp. Hairy Moccasin, for one, told Camp that “Custer’s command, as well as Boyer and the four Crows saw Reno’s fight in the valley.” He also claimed that the scouts watched the fight on Custer’s battlefield “quite a while and [until] satisfied ourselves that the soldiers there were whipped and killed.” Goes Ahead confirmed their observing Reno’s valley fight but stated that they “did not see Custer’s fight.” (He also told O.G. Libby that they witnessed Reno’s battalion dismounting in the valley to fight on foot.) White Man Runs Him added that “Custer sat on [the] bluff and saw all of Reno’s valley fight,” a statement that Camp dismissed as “entirely preposterous.” When Gen. Hugh Scott and Col. Tim McCoy interviewed the scout on the battlefield in 1919, he insisted that “Custer moved slowly and took his time and stopped occasionally. …Reno was fighting long before Custer moved.” White Man Runs Him also told Scott and McCoy that “Custer was reckless. Instead of Custer going ahead and starting at the same time as Reno, Custer held back and did not start until he saw Reno fighting. This was poor generalship.” However, Custer’s alleged pace and pause after ordering Reno to advance does not agree with the recollections of two enlisted men dispatched with messages to the regiment’s pack train and Capt. Frederick W. Benteen, whose battalion was scouting to the southeast on the left flank.

Sergeant Daniel Knipe of Company C informed Camp in 1908:

“Custer with his five companies followed Reno’s trail, on after him, some distance…[and] seeing about fifty or a hundred Indians on a bluff on the right of [the] Little Big Horn, he turned square[ly] to the right, increasing our speed. …[W]hen the command got up on the bluffs…we could see across the valley, see Reno with his three companies.(Italics added.)

Elsewhere Knipe remembered that when Custer ascended the bluffs, “we were then charging at full speed.”

— Edward S. Curtis, Courtesy Library of Congress, ca. 1908 —

Trumpeter John Martin, assigned to Custer as an orderly, was even more explicit as to the gait. At the 1879 Reno Court of Inquiry, he testified that the five companies “went on a jump all the way” after Reno advanced. “Always at a gallop,” he added. Years later he told Col. W.A. Graham that when Custer turned north:

“The General seemed to be in a big hurry. … We rode on [after viewing the village from “a big hill that overlooked the valley”], until we came to a big ravine that led in the direction of the river. …[W]e had been going at a trot or gallop all the way.” (Italics added.)

After Custer dispatched Martin with the message to Benteen to “be quick,” the trumpeter noticed that the command was descending the ravine at a gallop and soon under fire. As he returned on the trail he saw Reno’s fight in the valley just as the major’s dismounted skirmish line was “falling back,” presumably to the horses in the timber along the river. If this is true, Custer did not and could not witness Reno’s entire battle, as the scouts alleged.

Martin’s testimony also suggests that Custer did not observe the village, Reno’s fight or anything else at Weir Point because he was not there, based on the following exchange:

Q. Did you go to the top of that high point?

A. No, sir. Nobody but the Indian Scouts.

Q. Did not you and General Custer go to the top of it?

A. No, sir.

Such recollections by Custer’s troopers suggest that the scouts’ allegation is neither logical nor consistent with Custer’s character as a decisive man of action. To be sure, he had earned a reputation for rash, reckless insubordination in battle and elsewhere. Yet, he also demonstrated the ability to assess battlefield tactical situations accurately and react instantly, often with success. On the other hand, he had exhibited caution and restraint when confronted by what appeared to be unfavorable odds or a trap, as demonstrated, for example, at the 1864 Battle of Trevilian Station, the Washita fight in 1868 and his 1873 skirmishes with the Sioux on the Yellowstone River.

Curtis concluded that Custer “was not engaged until after Reno’s troops in their demoralized retreat had reached the top of the bluff and had been joined by Benteen.” This assumption might be true based on substantial testimony at the Reno Court of Inquiry and elsewhere that heavy volley firing to the north was heard shortly after Reno’s retreat.

However, we defer to the reader to judge the rest of the story.

C. Lee Noyes resides in Morrisonville, New York, with his wife, Michele, whom he credits with reviving and sustaining his longtime passion for the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn. He coauthored Last Man Standing: William Spencer McCaskey.