What poker hand was Wild Bill Hickok holding when he was killed in Deadwood in 1876?

Sam Malone, Decatur, Alabama

Hickok biographer, the late Joseph Rosa, addressed this many times—including in his book The Man and His Myth. He said, “In essence: Ellis ‘Doc’ T. Pierce, a self-styled blowhard (the opinion I have gleaned from an examination of some of his letters) claimed in his correspondence with writer Frank J. Wilstach in the 1920s that the cards Hickok held were the Ace of Spades, the Ace of Clubs, two black eights, Clubs and Spades, and the Jack of Diamonds, which became celebrated out West as ‘The Deadman’s Hand.’ But,” Rosa added, “the bottom line is nobody seems to know what particular poker game they were playing at the Number 10 Saloon in Deadwood that day.”

There was complete chaos after Jack McCall pulled the trigger. He pulled it several more times and all rounds misfired except the one that got Hickok. Cards went flying and people were scattering. I doubt anybody tried to look at the cards.

– Courtesy South Dakota Dept. of Tourism. –

How were telegraph messages delivered from one town to another?

Mario Raciti, Acicatena, Sicily, Italy

Like a post office letter, in addition to your message, the sender specified who the message was from, who it was intended for, and where they were located. The telegraph station would send it to the next nearest station, which would forward the message on until it got to the destination telegraph station. A California-to-New York message wouldn’t have been directly possible until 1861, when Western Union put a transcontinental line across the U.S.

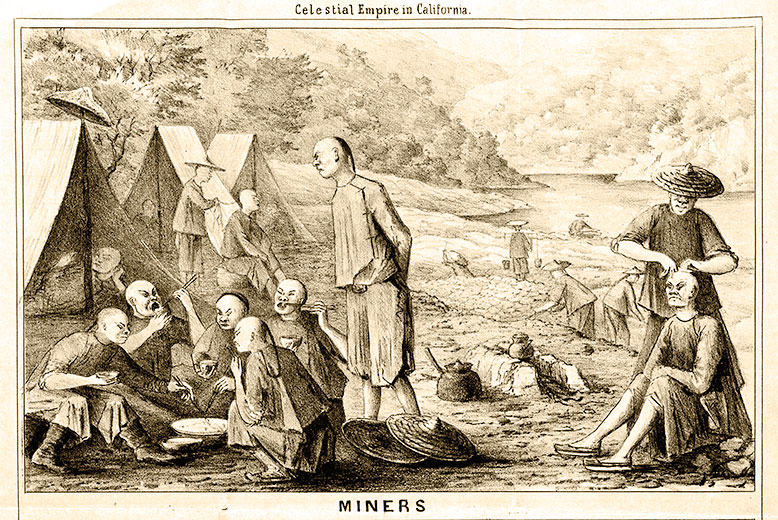

Old West newspapers often referred to the Chinese as Celestials. Any idea why they were called that?

Jim Spell, Marina, California

The Chinese used to refer to their nation as the “Celestial Empire.” The term Celestials was mainly used by whites to describe the Chinese, whom they saw as strange and foreign. To some whites, the term became a pejorative or an insult.

– Courtesy Library of Congress. –

What were the most common types of stagecoaches in the Southwest?

Ashley DeMello, London, United Kingdom

The classic image of the stagecoach is the Concord model, but for crossing the rough Western trails, passengers were often switched to lighter, Celerity or mud wagons.

John Butterfield chose Abbot-Downing for his stages because their suspension technology was best suited to the low relative humidity of the Southwest. Their wheels were the only ones that wouldn’t fall apart.

The Abbot-Downing Celerity was much lighter-built and often had a canvas roof and wooden sides. They were more common in the Southwest. The Celerity had leather side curtains rather than glass windows. The seats broke down so one could sleep. A Celerity could be successfully operated with a four-up hitch, but they were built for speed. Most often six-up hitches were used for that reason.

The third type was the lightweight and less expensive mud wagon, an extremely lightly built coach with canvas sides and roof. Mud wagons had very wide wheels and iron tires and were used primarily in bad weather, when the mail absolutely had to go through.

The Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach could travel 110 miles in a 24-hour day, with an average speed of a little over 4.5 miles per hour. The cross-country stage road wasn’t too mountainous until it reached New Mexico and Arizona.

The Butterfield Stage Line had 100 Concord coaches at its peak and employed nearly 800 men. They owned over 1,000 horses and mules and had 150 full-time drivers. Coach fare from St. Louis was $100 and the trip took an average of 23 days. Butterfield’s contract was cancelled in 1861, at the outbreak of the Civil War. For further reading, I suggest Gerald T. Ahnert’s The Butterfield Trail and Overland Mail Company in Arizona 1858-1861.

– Courtesy Library of Congress. –

General George Crook preferred to ride a mule. Could an enlisted man choose such a mount?

Paul Gordon, St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada

I did some checking with author John Langellier, and found that in the frontier Army, an enlisted man could request a mule, if the quartermaster had any on hand. Mules were surefooted in the mountains and withstood the Southwestern desert heat better than horses.

How did travelers on wagon trains hang a criminal in areas where there were no trees?

Ben Allen, Atlanta, Georgia

No trees, no problem. Wagon trains had a code of conduct for extremely bad behavior such as murder and rape. A couple of family diaries told about a murderer’s trial and conviction:

“Two respected men were chosen to serve as a judge and a sheriff, who in turn chose a 12-man jury. After the jury had heard the evidence they returned 20 minutes later with a verdict of guilty. Afterwards, a crude scaffold was made by pushing two wagons together. Their tongues raised high and tied together. The hanging rope was anchored to the two tongues then a noose was looped around the convicted man’s neck and he was pushed off the wagon seat as the wagon train members looked on.”

Marshall Trimble is Arizona’s official historian and vice president of the Wild West History Association. His latest book is Arizona Oddities: Land of Anomalies and Tamales; History Press, 2018. If you have a question write: