After American troops spent four years fighting the Civil War, the struggle to restore the Union ended with powerful victories by the Northern Army. President Abraham Lincoln’s massive million men, clad in blue and wielding terribly swift swords, dwindled to a small contingent of Regulars, most of whom were stationed beyond the Mississippi River.

After American troops spent four years fighting the Civil War, the struggle to restore the Union ended with powerful victories by the Northern Army. President Abraham Lincoln’s massive million men, clad in blue and wielding terribly swift swords, dwindled to a small contingent of Regulars, most of whom were stationed beyond the Mississippi River.

These men served at far-flung, often isolated outposts as constabularies.

“We are about 1,000 miles from nowhere excepting it be the verges of Hell, and I think we ‘ain’t no more nor’ ten rods from that delightful spot,” wrote Second Infantry Lt. Col. Josias King, whose attitude about Fort Larned, Kansas, could have been echoed at almost every frontier outpost.

Hollywood often made a big show out of the post-Civil War cavalry at these frontier forts, riding with guidons snapping in the breeze and bugles blaring as they galloped to the rescue. The real-life cavalrymen themselves felt superior to the foot troops, as evidenced by Samuel Chamberlain, a dragoon who fought in the Mexican-American War of 1846-48: “No man of any spirit and ambition would join the ‘Doughboys’ and go afoot….”

Yet the infantry also played a major role in protecting and pacifying the West. These walking soldiers performed unglamorous, tedious tasks, such as denying watering holes to the enemy, escorting paymasters (a grueling assignment in the northern climes during the winter), guarding supply trains and railroad construction crews, building roads and patrolling the troubled border with Mexico. They also protected the “talking wires,” as some American Indians called the telegraph.

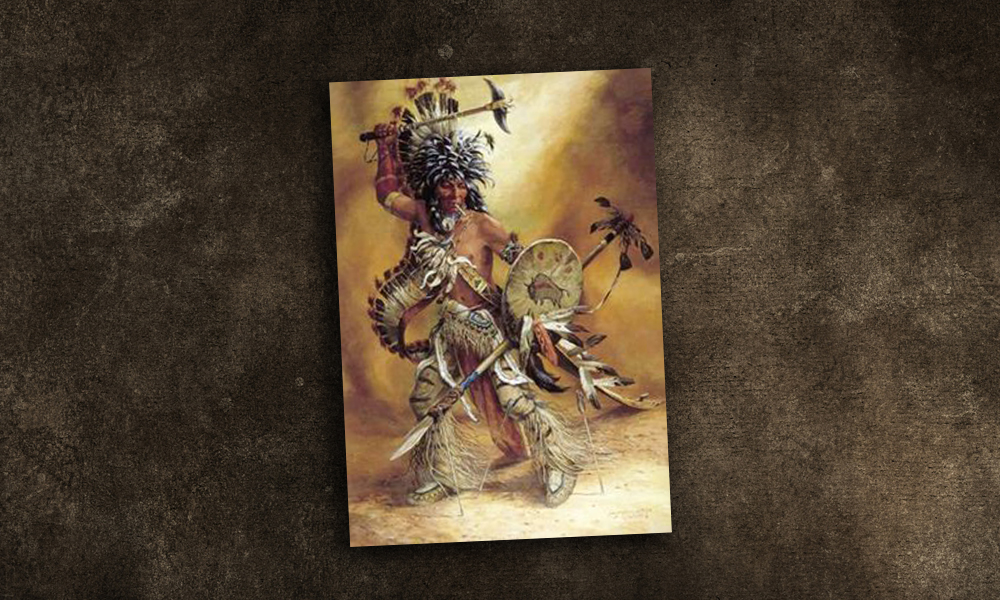

The Indians they encountered dubbed their hard-marching adversaries “walk-a-heaps.” When a contingent of the Seventh Infantry approached his Lakota village, Red Horse indicated his people were “afraid of them, and so we moved away.” He concluded this action was wise because “Indians can’t fight walking soldiers.”

Trials and Tribulations

Achieving such praise from a brave fighting man did not offset the trials and tribulations of these walk-a-heaps. Duty was difficult and typically tedious. Promotion was slow; pay paltry. For example, a private received only $13 a month (a $3 reduction from the wartime sum) during his first enlistment, which lasted from three to five years.

The “result of poor pay is poor sergeants,” Brig. Gen. E.O.C. Ord stated, “and, as a rule, the line [infantry] does not get non-commissioned officers who command the respect or obedience of the men.”

Infantry soldiers also resented being worked as day laborers to construct military posts, chop wood, cut hay and other non-soldierly assignments. Little wonder that desertion ran rampant among the rank and file.

Circumstances were little better for officers. Upward mobility that brought a higher wage moved at a snail’s pace. Below the grade of major, the regiment determined if an officer received a promotion, and stagnation was the norm. Usually death, resignation or retirement offered the only path up the ladder.

Given that retirement was not set at a mandatory age of 65 until 1881, some officers clung to their positions for decades. William R. Shafter held the colonelcy of his First Infantry for 18 years. C.F. Smith of the 19th Infantry remained at the helm of his unit for 22 years. George Andrews of the 25th Infantry spent 21 years in charge of his black foot soldiers, and so it went for many others. Senior officers who lingered blocked younger, and sometimes more capable, subordinates from advancement.

The Sad Situation

By 1869, only 25 infantry regiments remained on the rolls, and the number of privates and non-commissioned officers regularly ran less than four dozen per company. Even that figure was high for some companies. During 1876, one infantry officer claimed the largest company in his regiment fielded only seven men; in another company, only the captain and first sergeant appeared at the mandatory weekly parade.

These statistics alarmed commanders, including Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan, the second-highest ranking member of the U.S. Army’s “brass” for many years after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender to the Union troops. Commenting on the sad situation, in 1878, “Little Phil” reported:

“No other nation in the world would have attempted the reduction of these wild tribes [in the West] and occupation of their country with less than 60,000 or 70,000 men, while the whole force employed and scattered over the enormous region…never numbered 14,000 men, and nearly one-third of this force has been confined to the line of the Rio Grande to protect the Mexican frontier.”

Adapt, or Die

When not in garrison tending to monotonous tasks—ranging from cleaning equipment to mending wool uniforms to raising food that supplemented the rather Spartan rations provided by Uncle Sam—the doughboys were sent on campaign.

Having received no basic training before being sent off to these far-off forts, recruits learned field craft from veteran comrades. Prior to the mid-1870s, they also received little-to-no instruction in the use of their rifles, which often changed as the Army transitioned from muzzleloaders to breechloaders during the 1860s through the turn of the 20th century.

What was printed in the Army manuals did not always prepare the infantryman for combat against a fierce foe, whether on the freezing Great Plains or in the torrid deserts of the Southwest. Once a soldier encountered an enemy, adaptation could determine failure or success.

At Wyoming Territory’s Fort Phil Kearny, less than three dozen foot soldiers from Capt. James Powell’s 27th Infantry bested far superior odds. From behind a makeshift bastion made of wagon boxes, they faced and vanquished valiant Lakotas mounted on sturdy steads.

The determined defenders, armed with recently issued Springfield Model 1866 .50-70 converted “trapdoors,” repelled charge after charge, at a cost of six dead and two wounded, as opposed to an estimated 60 Lakotas killed.

“But never, before or since, have my nerves ever been put to the test they sustained on that terrible 2d of August, 1867, when we fought Red Cloud’s warriors at the wagon-box corral,” recalled one of the surviving victors, Pvt. Samuel Gibson, who ultimately served 48 years in the infantry.

During the 1877 Nez Perce War, a contingent of the Fifth Infantry obtained captured war ponies that allowed them to become mounted riflemen. The regimental commander, Nelson A. Miles, somewhat facetiously referred to this ad hoc strike force as the “11th Cavalry”—an apt sobriquet, since the Army only had 10 cavalry regiments at that time.

At Bear Paw Mountains, this cavalry helped dislodge the resolute Nez Perce. Charging into action, the soldiers dismounted and “threw themselves upon the ground, holding the lariats of their ponies in their left hands, and opened a deadly fire with their long-range rifles….”

The troops then dug rifle pits in the hard ground, where they remained for five days under fire. Adding to the plight of the plucky foot soldiers, the weather disintegrated to sleet and snow.

During the battle, First Sgt. Henry Hogan slung a Fifth Infantry officer over his shoulder while under heavy fire. He went on to earn his second Medal of Honor—a rare accomplishment. In 68 instances, infantry officers and enlisted men were recognized for performing above and beyond the call of duty, resulting in the Medal of Honor. The first of this distinguished band of brothers was Third Infantry Sgt. James Fagan. In March 1868, while in charge of a wagon train carrying gunpowder from Kansas’s Fort Harker to Fort Dodge, Fagan single-handedly drove off bandits intent on freeing a deserter.

Even when wounded, infantrymen proved their daring. In 1869, First Lt. George Albee of the 41st Infantry led a wild charge with only two men against a war party of 11. During 1872, an 11th Infantry private drove off an Indian attack against a mail coach in Texas. Sergeant Benjamin Brown of the 24th Infantry sustained a wound in the abdomen and both arms, yet he continued to blaze away against desperados who ambushed an Army paymaster with tens of thousands of dollars in military pay.

In the end, infantry operations during the Indian Wars were difficult, expensive and frequently fruitless. For every banner headline in the press, scores of other engagements went unreported and were all but forgotten. Yet the valiant service of these walk-a-heaps and dust-covered doughboys helped carve a community out of the wilderness.

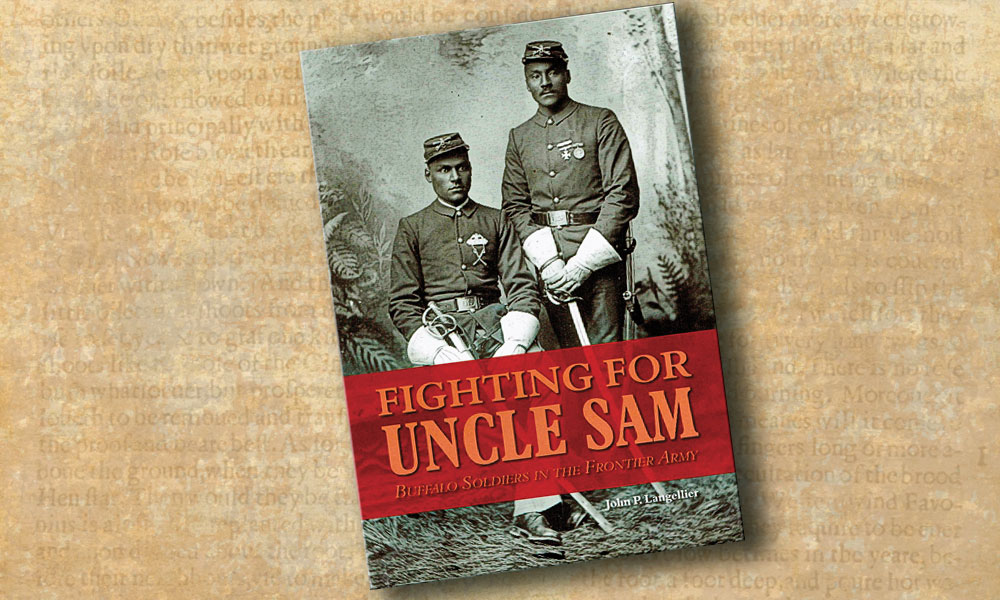

John Langellier received his PhD in military history from Kansas State University. After a 45-year career in public history, he retired in Tucson, Arizona, in 2015. He is the author of dozens of books, including Fighting for Uncle Sam: Blacks in the Frontier Army, due out in early 2016.

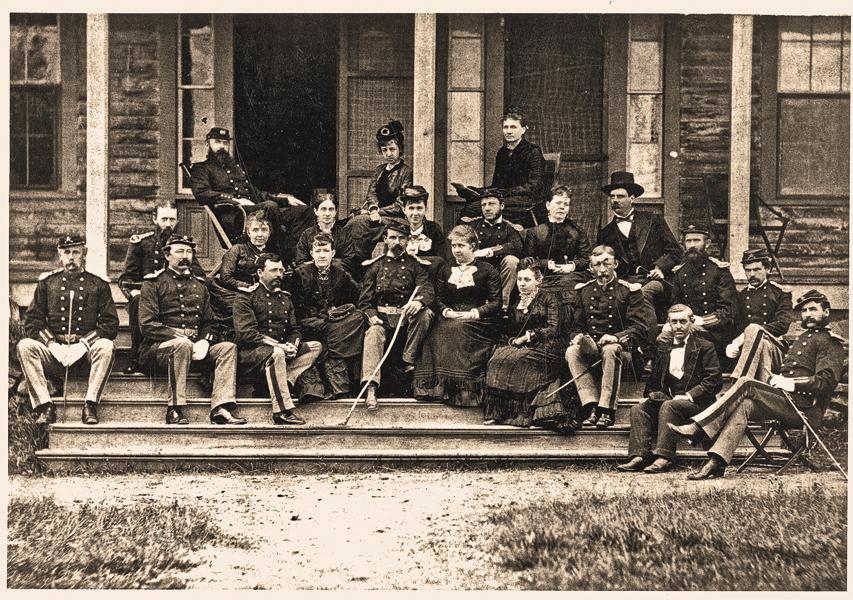

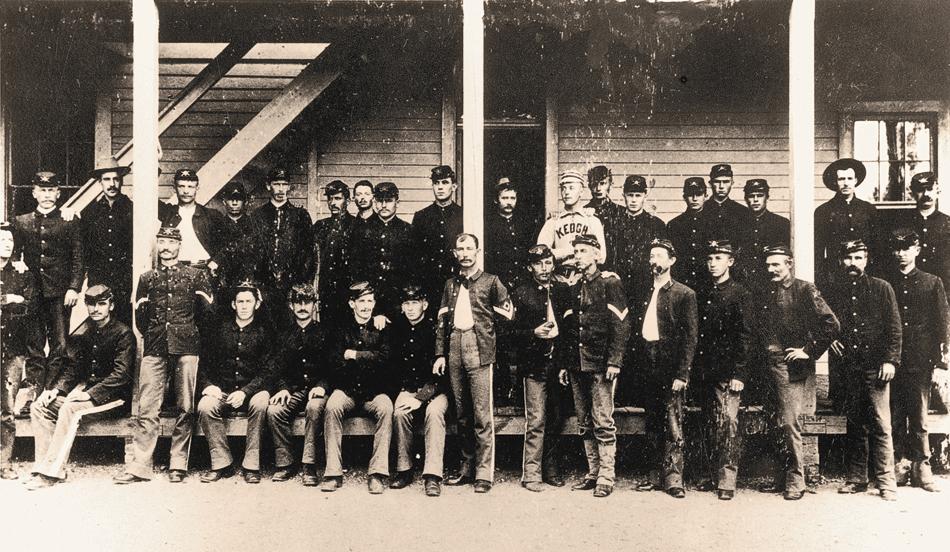

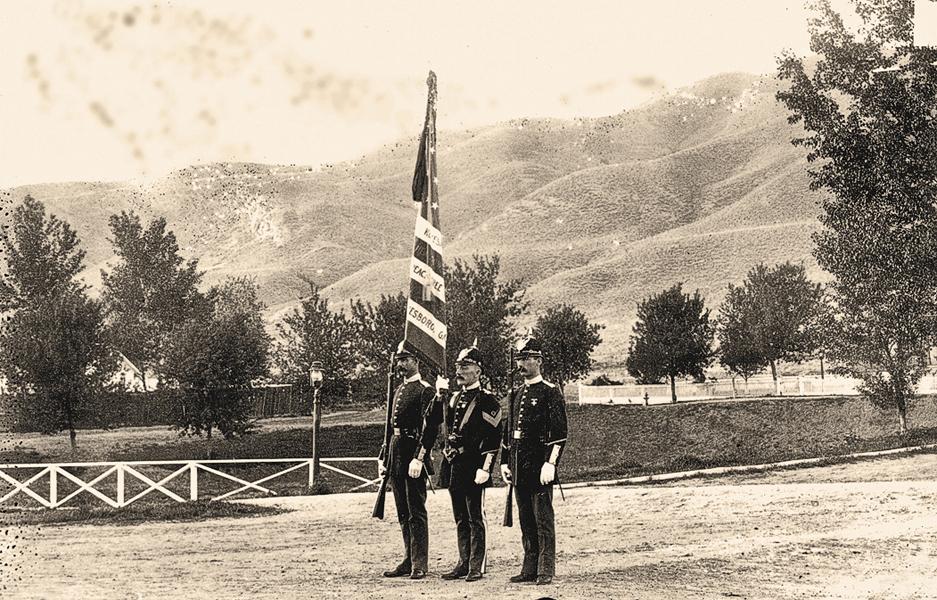

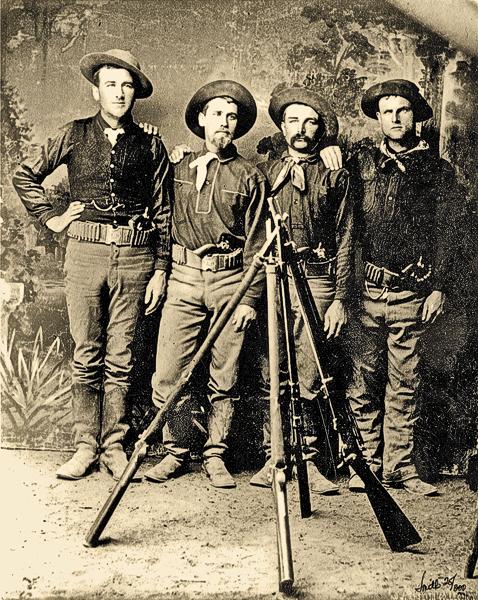

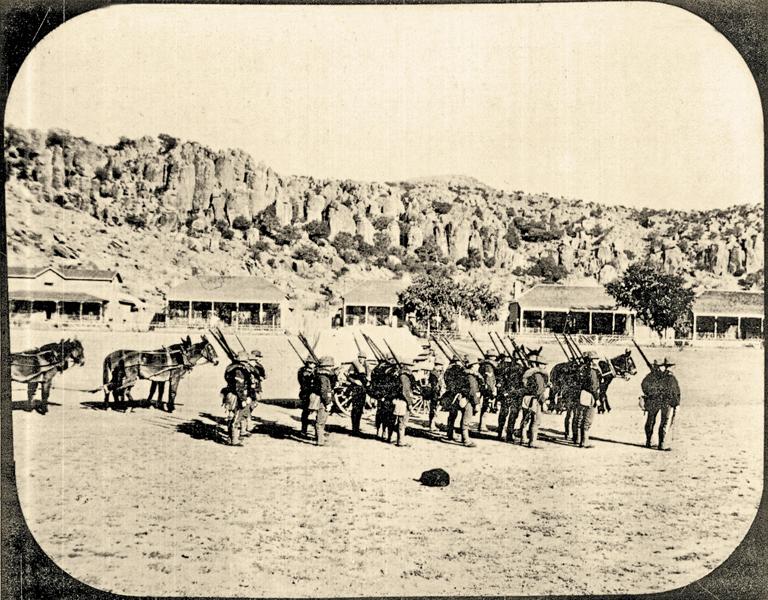

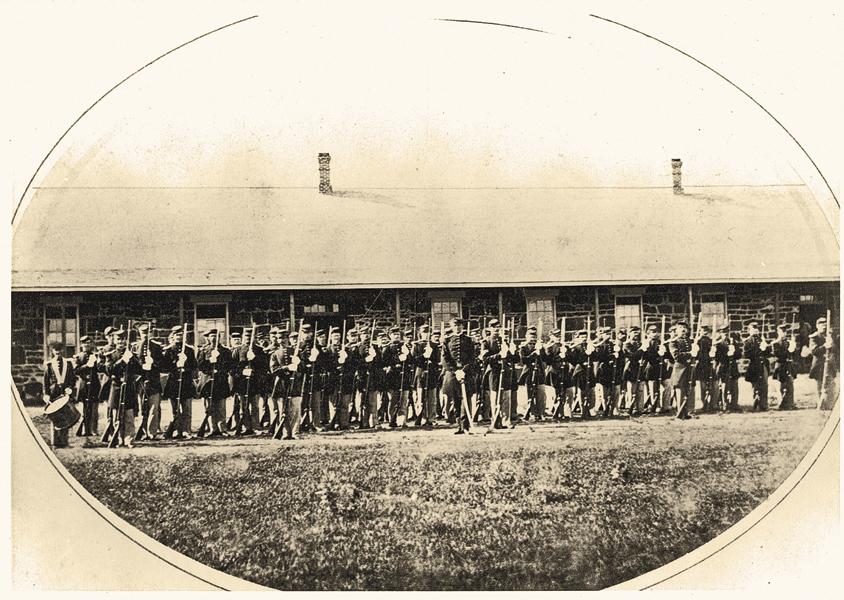

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

– Courtesy Wyoming State Archives and Historical Department –

– Courtesy Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Archives, Salt Lake City –

– Courtesy Glenn Swanson Collection –

– Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University –

– Courtesy Kansas State Historical Society –