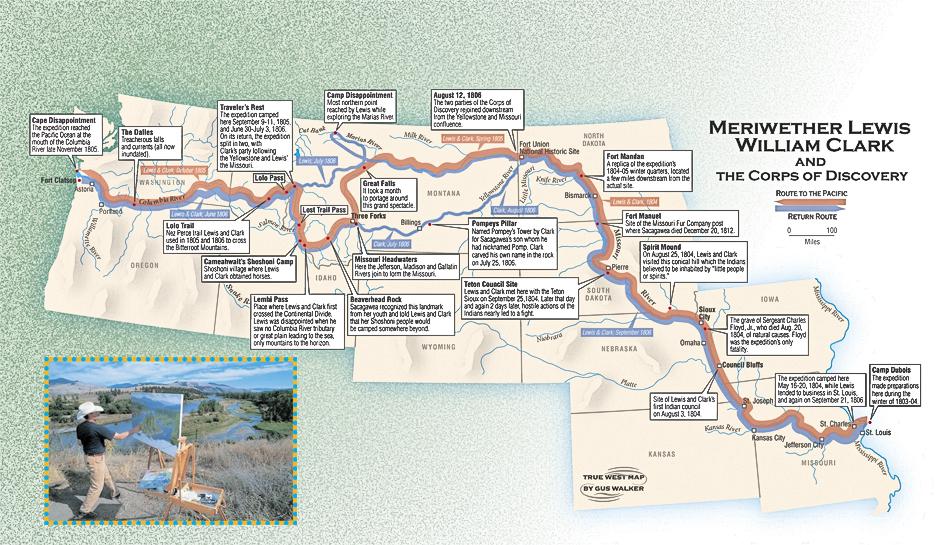

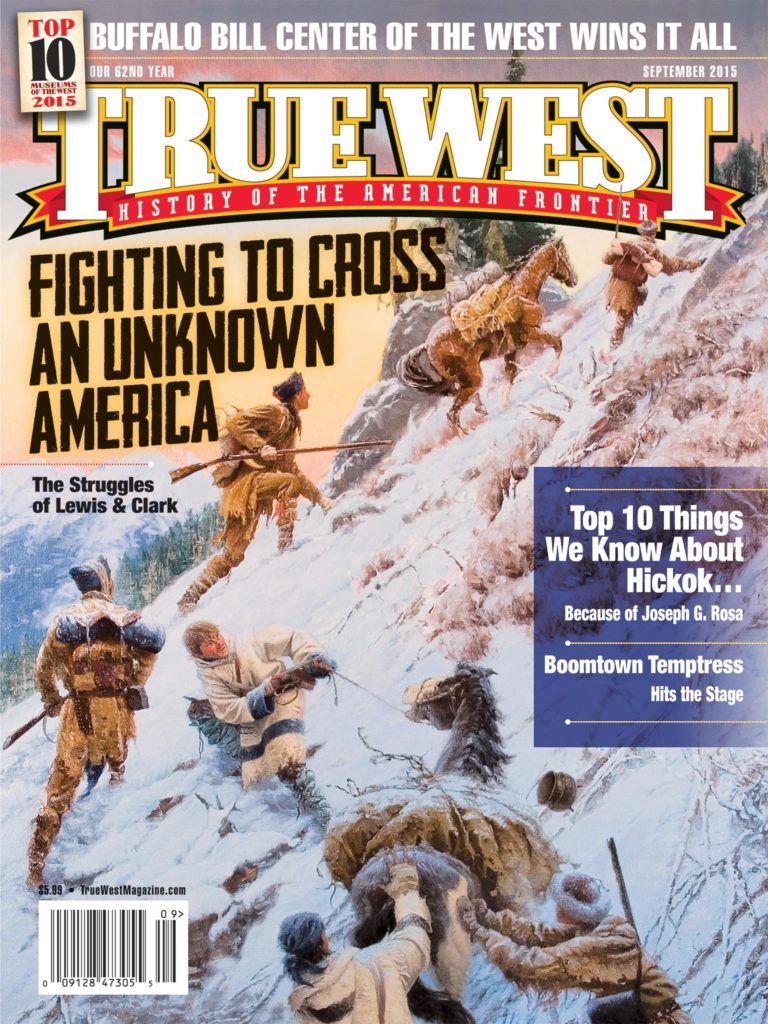

How many times was Death “swinging his scythe” at the Corps of Discovery? At least 56 hair-raising incidents could have killed the crew during the 28-month, 8,000-mile journey, with William Clark most at risk. The captain fell peril to at least five accidents, while his partner, Meriwether Lewis, almost died twice while climbing bluffs (and was shot at three times).

How many times was Death “swinging his scythe” at the Corps of Discovery? At least 56 hair-raising incidents could have killed the crew during the 28-month, 8,000-mile journey, with William Clark most at risk. The captain fell peril to at least five accidents, while his partner, Meriwether Lewis, almost died twice while climbing bluffs (and was shot at three times).

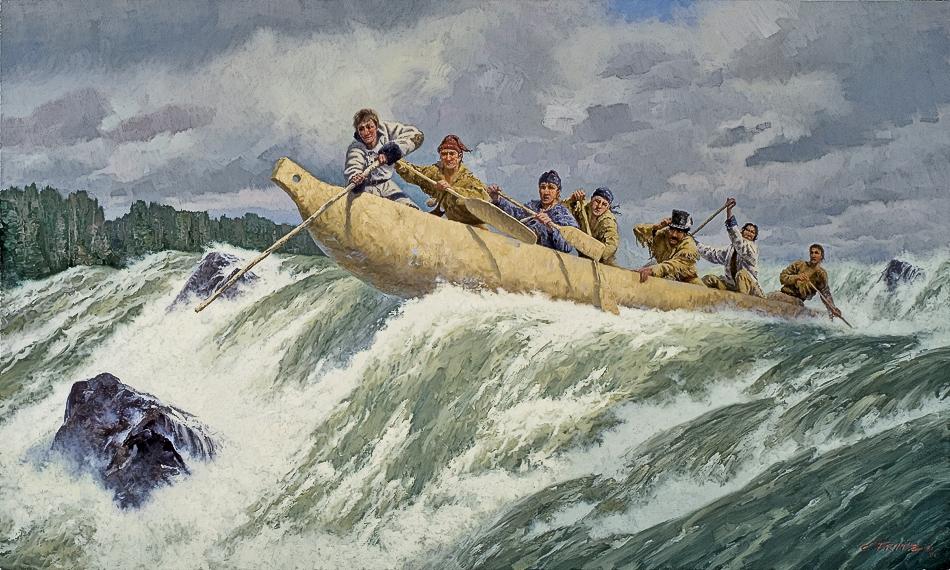

Old Man River proved a formidable foe. When the captains set off in 1804, their keelboat ran afoul many times, placing the crew in imminent danger. The most harrowing description came on September 30: “…the Sturn of the boat got fast on a log…was verry near filling…the Chief on board was So fritened…he ran off and hid himself….”

Though Lewis and Clark made survival skills a high priority for the men they recruited for the cross-country expedition, some men could not swim—strange for a journey largely traveled on rivers. Toussaint Charbonneau almost drowned on several occasions, with Clark notably saving his life on July 26, 1805.

The elements tested the explorers. The crew remarkably escaped a “truly tremendious” prairie fire at Fort Mandan in October 1804 that burned a native man and woman to death. Flames got even closer, in May 1805, when a tree caught fire above the captains’ lodge, where they were staying with Charbonneau, his wife, Sacagawea, and baby; just after they frantically moved the lodge, the tree fell: “had we been a few minutes later we should have been crushed to attoms.”

Snow proved brutal as well, particularly during one storm, when the men, who had been moving baggage over the plains, were “sorely mawled with the hail which was so large and driven with such force by the wind that it nocked many of them down…most of them were bleeding freely….”

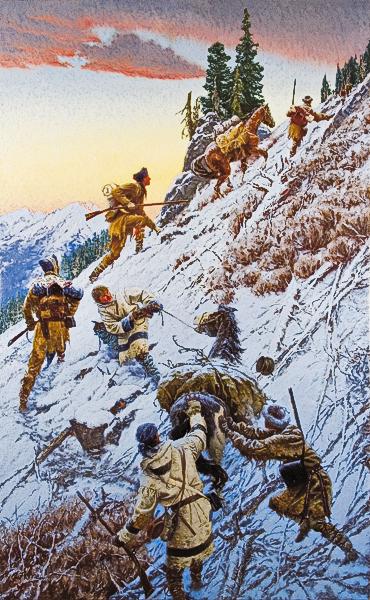

Lewis recorded the “most wonderful escape [he] ever witnessed” on September 19, 1805. While the party climbed a steep precipice, Robert Frazer’s horse fell and rolled, with his load, nearly 100 yards into a creek, down a hill “broken by large irregular and broken rocks.”

Everyone expected to see a dead horse, he noted, but the animal got up, barely injured, and it proceeded on within 20 minutes.

Beasts of brute strength added to the chaos. On May 11, 1805, the travelers encountered the worst of the monstrous grizzly bears, a beast they had shot in the lungs that continued to pursue William Bratton for half a mile. After the men finally shot two balls into the bear’s skull, Lewis wrote, “these bear being so hard to die reather intimidates us all….”

Even Seaman, a Newfoundland dog, got bit by a beaver in the hind leg, which cut off an artery. Lewis, who had trouble stopping the blood, wrote, “I fear it will prove fatal to him.”

But 10 days later, on May 29, 1805, Seaman saved the crew when he changed the course of a huge buffalo bull charging at some men sleeping by a campfire.

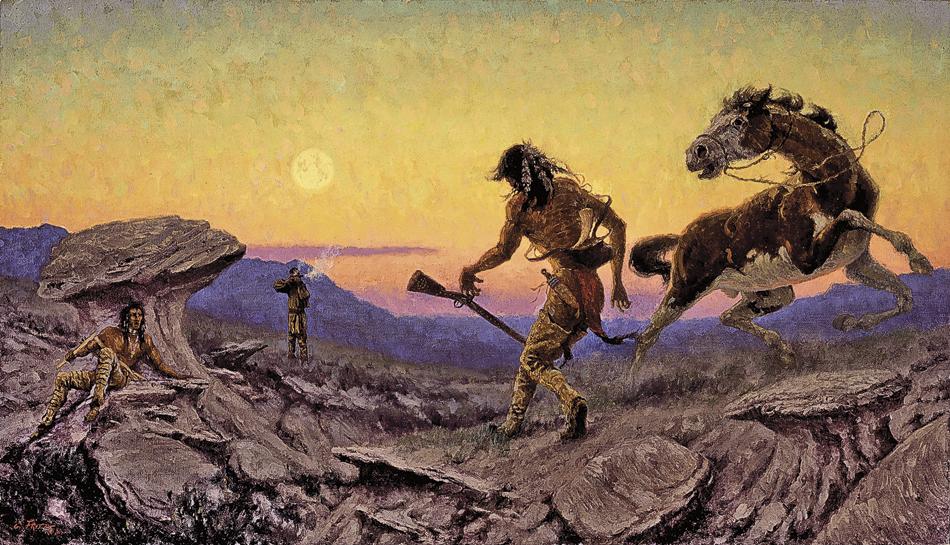

The crew experienced only five hostile encounters with native peoples. The most famous fight took place on July 27, 1806, along the Two Medicine River. A party of eight Piegan Blackfeet stole the rifles of Lewis and his men while they were asleep. In a skirmish to recover the weapons, Reubin Field fatally stabbed an Indian, and a gunshot fired by Lewis may have killed another. When the Piegans dispersed, possibly to get more warriors, the crew beat a desperate retreat, nonstop, more than 100 miles to the Missouri River.

Lewis not only escaped death by gunfire in that battle (he “felt the wind of [a Piegan’s] bullet very distinctly”), but two more times, from accidental gunfire by members hunting with him; one shot wounded him! Hunting, of course, was paramount to the group’s survival: all the boats, weapons and scientific instruments they had to bring along left them to shoot most of their food. Lewis gave marksman George Drouillard the credit for getting the crew across modern-day Montana, Idaho and Oregon without starving.

In that unknown country, only one man did not survive the trip: Sgt. Charles Floyd. He died of an infection, likely from a ruptured appendix, an illness not understood by doctors for at least two more decades.

When the expedition returned to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1806, the nation hailed the men for their stupendous achievement in survival.

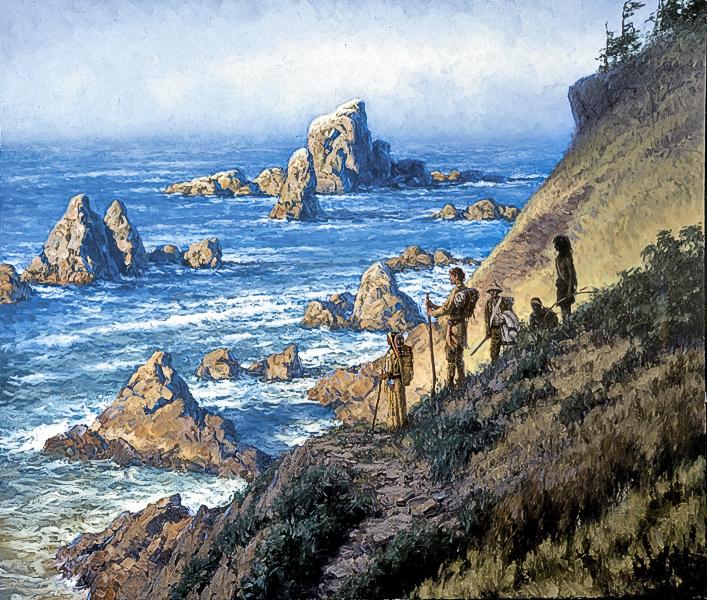

President Thomas Jefferson had gotten what he wanted: the scientific and geographic knowledge about a territory the U.S. bought from France in 1803—the Louisiana Purchase included land from 15 present-day states and two Canadian provinces. But he failed by not sending a professional artist along for the trip.

By the time America marked the 200th anniversary of the expedition, Montana artist Charles Fritz had brought the journey to life. Beyond painting major moments documented in the expedition journals, Fritz traveled and camped out along the entire route—from St. Louis to the Pacific Coast—at least twice. Even more, he visited the sites at the same time of the journal entries, painting on location, to ensure he was accurately portraying the flora, fauna and setting, and properly communicating a humid Missouri summer or the blasting roaring winds of the Columbia River Gorge.

Fritz relied on the journals and on other historical records to overcome one major challenge: the original route is forever changed. Over the past 200 years, rivers have altered their course and, furthermore, dams, agriculture and other settlements have left their marks on the land.

In 2004 the Montana Museum of Art and Culture premiered the collection, then numbering 72 paintings, which traveled all over the nation during the Bicentennial, 2004-2006. Today you can experience the journey through the completed collection of 100 of Fritz’s paintings at Arizona’s newest museum, Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, through October 31, 2016.

Like Clark, you may feel a “secret pleasure” in these men’s struggle to cross an uncharted land. When Clark reached the head of the “boundless Missouri,” he reflected “on the difficulties which this Snowey barrier would most probably throw in my way to the Pacific Ocean, and the Sufferings and hardships of my Self and party in them, it in Some measure Counter ballanced the joy I had felt in the first moments in which I gazed on them.

“But,” he continued, “as I have always held it little Short of Criminality to anticipate evils I will allow it to be a good Comfortable road until I am Compelled to believe otherwise.”

Such valiant optimism no doubt helped pave the road to success for these brave men fighting to cross an unknown America, who all emerged in glory when their journey came full circle in 1806.

For an account of the Corps of Discovery’s narrow escapes of survival, read Robert R. Hunt’s essay in Volume Two of Explorations into the World of Lewis and Clark, edited by Robert A. Saindon. Please note: Misspellings in quotations match journal entries.

Photo Gallery

July 27, 1806: “…I called to them…that I would shoot them if they did not give me my horse and raised my gun, one of them jumped behind a rock…and stoped at the distance of 30 steps from me and I shot him through the belly….”

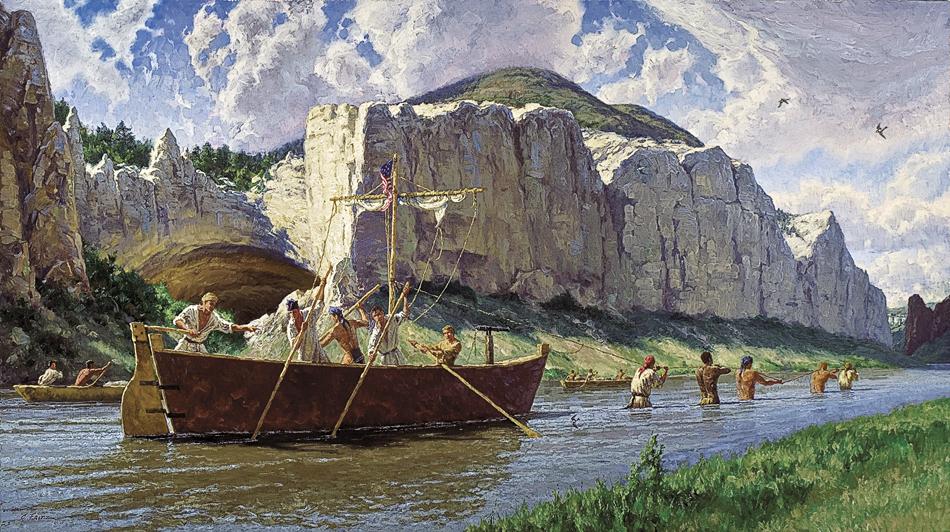

May 31, 1805: “…the banks and bluffs along which they are obliged to pass are so slippery and the mud so tenacious that they are unable to wear their mockersons, and in that situation draging the heavy burthen of a canoe and walking ocasionally for several hundred yards over the sharp fragments of rocks which tumble from the clifts and garnish the borders of the river; in short their labour is incredibly painfull and great, yet those faithfull fellows bear it without a murmur.”

– Courtesy Charles Fritz –

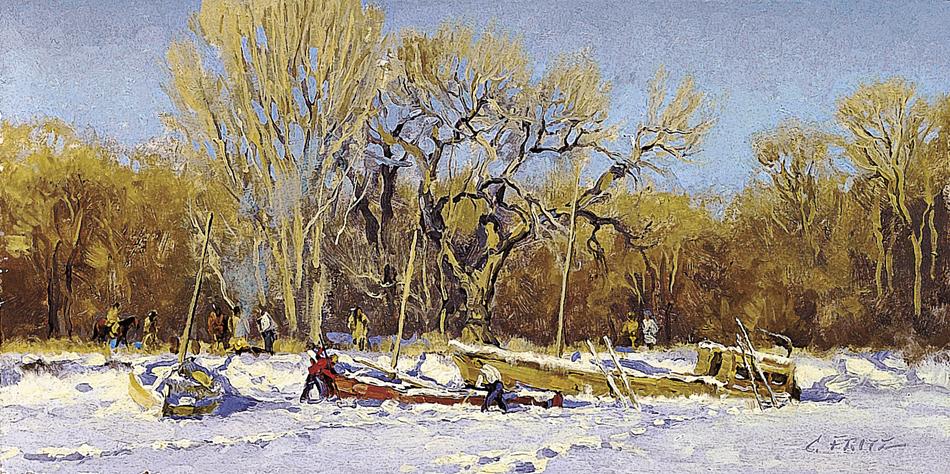

The journey canoeing down the Columbia River was hardening enough, as was the day-long experience of manhandling the equipment and canoes over the Celilo Falls portage, particularly when swarmed by fleas.

October 23, 1805: “Took the Canoes over the Portage on the Lard. Side with much dificuelty…one Canoe got loose & cought by the Indians which we were obliged to pay. our old Chiefs over herd the Indians from below Say they would try to kill us…every man of the party was obliged to Strip naked dureing the time of takeing over the canoes, that they might have an oppertunity of brushing the flees of their legs and bodies—”

Crossing the Rocky Mountains was a particularly hazardous stretch for the explorers. On September 16, 1805, Patrick Gass recorded this account: “Last night about 12 o’clock it began to snow. We renewed our march early, though the morning was very disagreeable, and proceeded over the most terrible mountains I ever beheld…. The snow fell so thick, and the day was so dark, that a person could not see to a distance of 200 yards. In the night and during the day the snow fell about 10 inches deep.”

– Illustrations by Charles Fritz and Courtesy Tim Peterson Family Collection –

February 23, 1805: “All hands employed in Cutting the Perogus Loose from the ice, which was nearly even with their top…after Cutting as much as we Could with axes, we had all the Iron we Could get & Some axes put on long poles and picked throught the ice….”

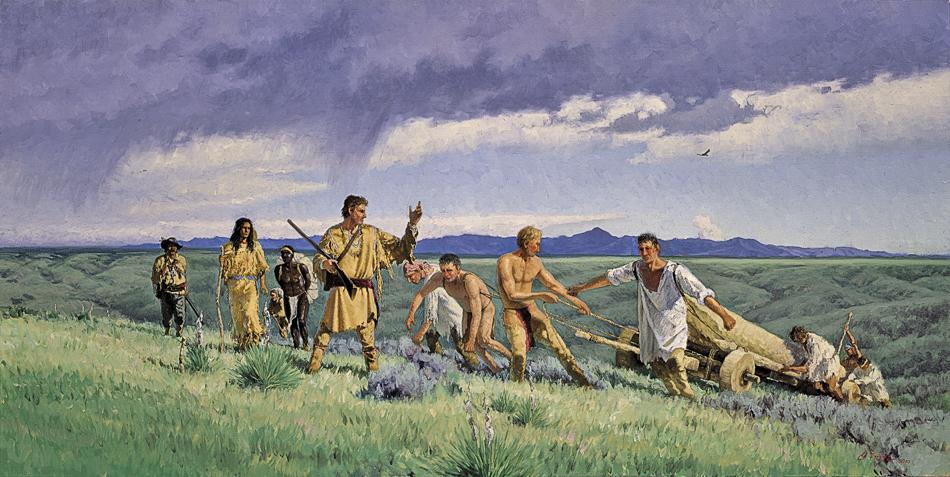

June 23, 1805: “…the men has to haul with all their Strength wate & art, maney times every man all catching the grass & knobes & Stones with their hands to give them more force in drawing on the Canoes & Loads…. Some become fant for a fiew moments, but no man Complains all go Cheerfully on—”

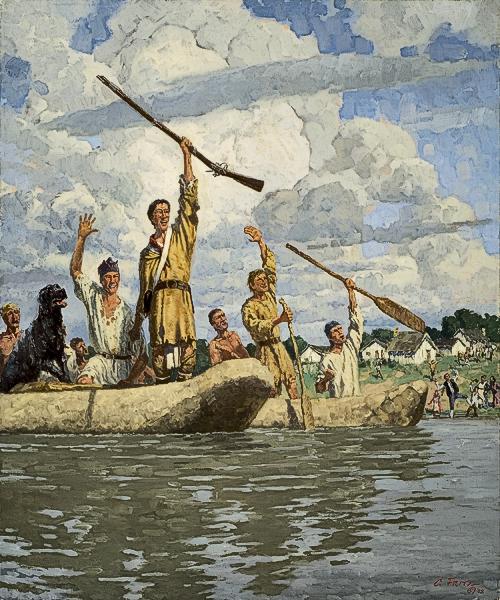

September 23, 1806: “…Set out descended to the Mississippi and down that river to St. Louis…we Suffered the party to fire off their pieces as a Salute to the Town. we were met by all the village and received a harty welcom from it’s inhabitants….”