— Courtesy John Langellier —

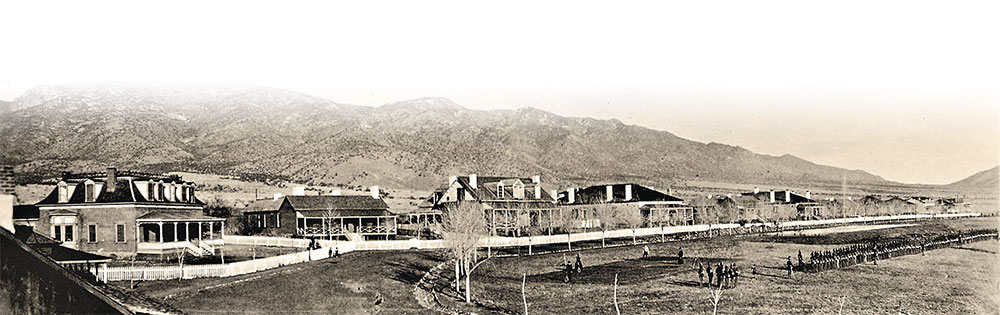

Dateline: Fort Grant, Arizona Territory, Saturday, May 23, 1896.

Edgar Rice Burroughs, age 20, arrived here today to begin a harrowing ten-month tour of duty with the 7th U.S. Cavalry. A graduate of Michigan Military Academy, Burroughs had recently failed the entrance exam to West Point. Yet youthful optimism led him to believe a commission might still be attained from the ranks. Enlisted at Detroit with consent of his father (former Civil War Maj. George Tyler Burroughs), underage Ed had now achieved his rather perverse but expressed desire to be sent to “the worst post in the United States.” At Fort Grant his high hopes for rapid advancement would soon be crushed upon hard Arizona rocks.

— Courtesy Sulphur Springs Valley Historical Society —

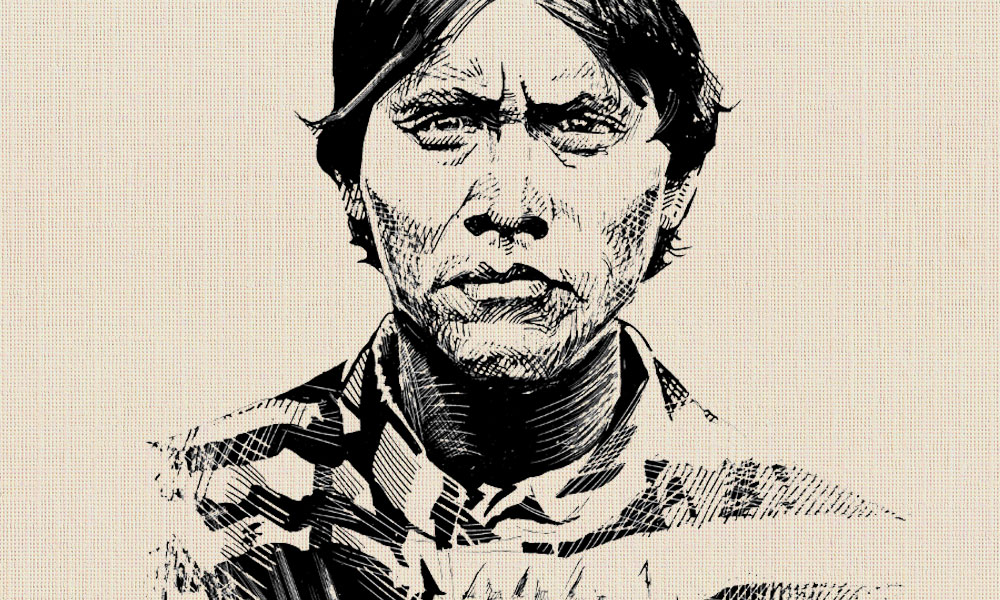

Unknown to Burroughs, those same jagged rocks concealed a living legend—the Apache Kid. Kid roamed ghost-like through the remote mountain vastness, a $5,000 bounty on his head on both sides of the border. Edgar Rice Burroughs, whose own legend was still unlit, would soon join the hunt for this famed phantom outlaw—thus tying his name forever to the Apache Kid saga.

— True West Archives —

Burroughs’ Arizona adventure began the previous day in the roughneck cowtown of Willcox. Arriving by rail with one dollar in his pocket, he had missed the daily mail and passenger stage to the fort. “Terribly hungry and equally sleepy,” Ed found a room at (probably) the Willcox Hotel. Bedeviled by bed bugs Burroughs abandoned his cot, spending most of his first night in Arizona perched uncomfortably on the hotel’s front porch.

Posted to Fort Grant

— All Sketches and Images Copyright Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., Unless Otherwise Noted/ All Sketches made by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Fort Grant, A.T., 1896-97 —

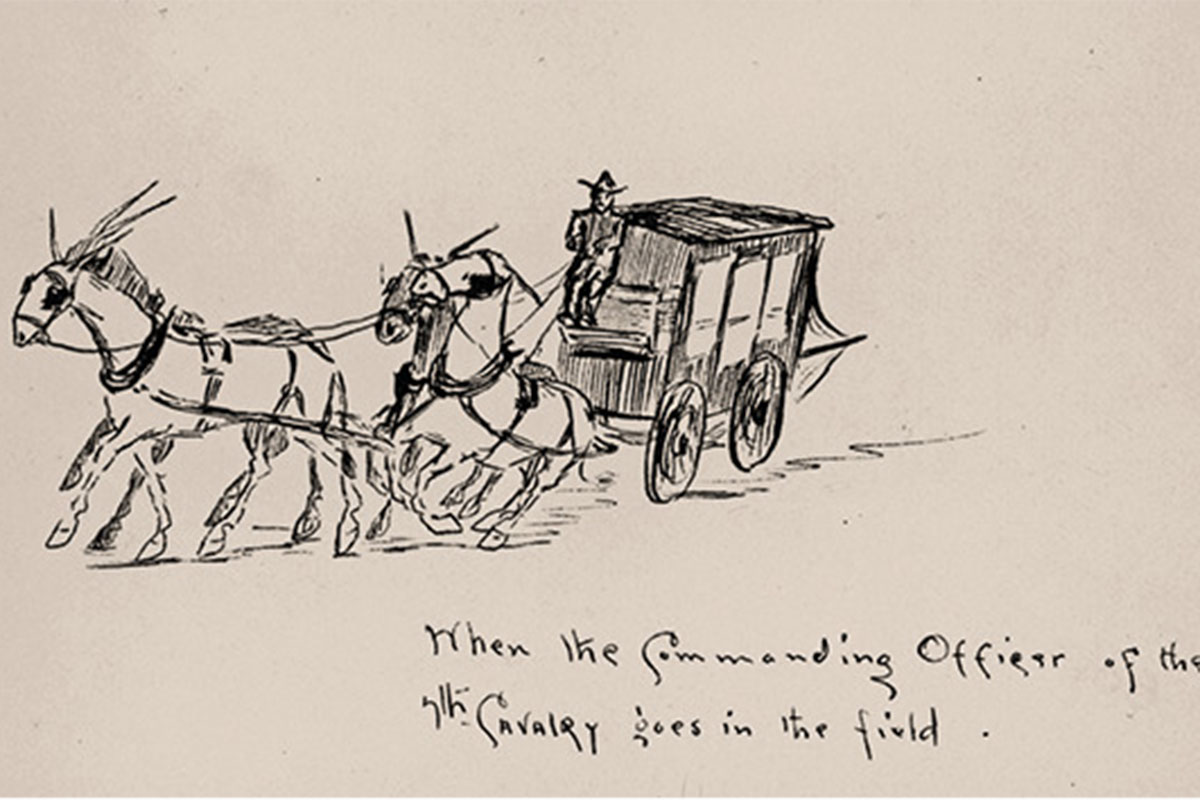

The following morning Burroughs boarded the stagecoach for Fort Grant (possibly driven by Warren Earp). Decades later, Ed recalled of this trip: “There were other passengers, but only one whom I remember, a painted lady from the hog ranch three miles from the post… She was not very old, but she was motherly and kind hearted. We dropped her at the hog ranch and I never saw her again.” One can only wonder if this “painted lady” voiced some encouraging words to new recruit Burroughs, headed to his first duty station. Her kindly impression lingered with him for life.

— Courtesy John Langellier —

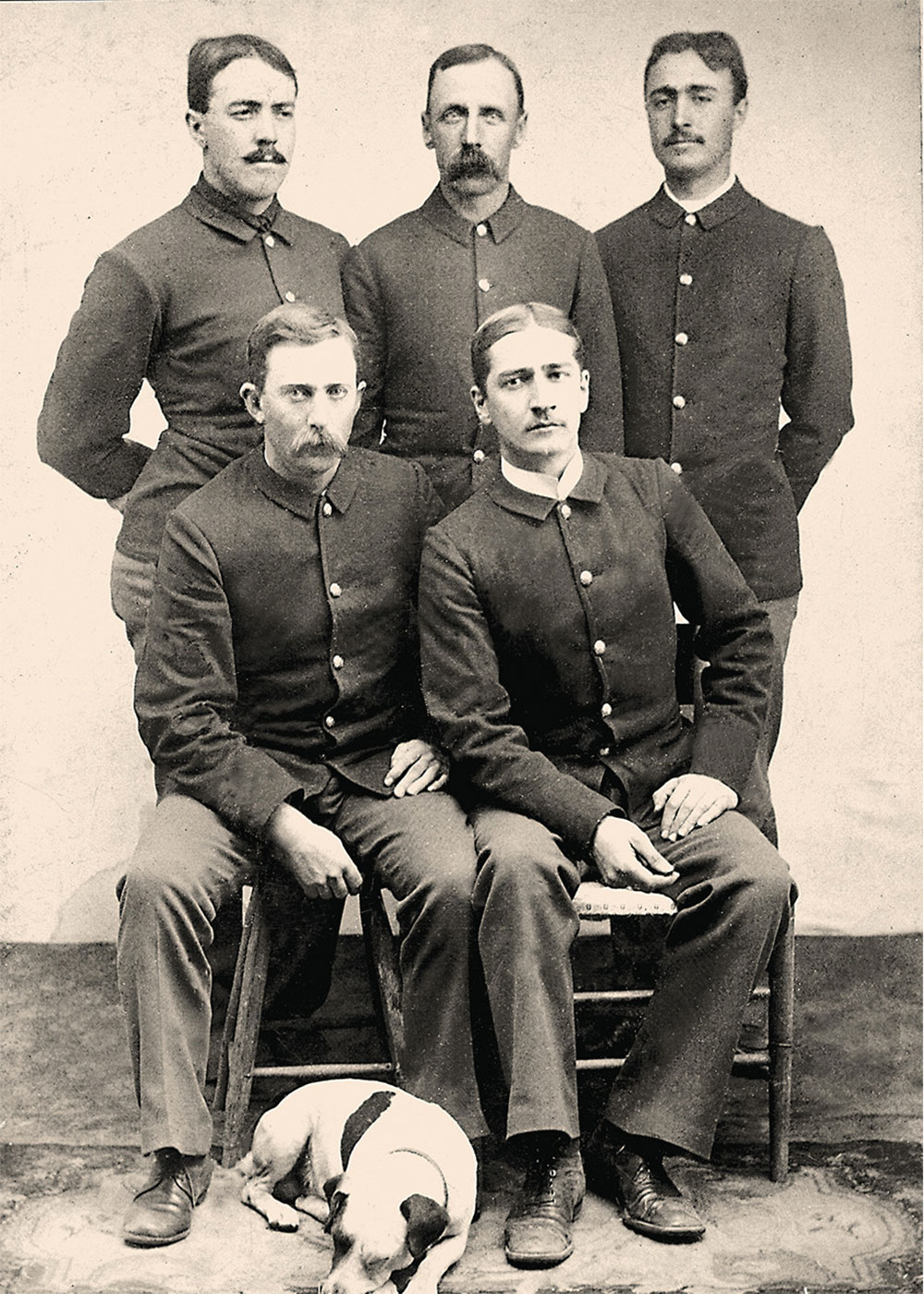

Sworn in and assigned to Troop B, U.S. 7th Cavalry under command of 1st Lt. Selah R. H. “Tommy” Tompkins, Pvt. Burroughs now began his training and indoctrination. An accomplished horseman, he easily adapted to mounted cavalry drills. Saber exercises he quickly mastered as well.

— Sketch of Stagecoach Copyright Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., Made by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Fort Grant, A.T., 1896-97 —

— Courtesy True West Archives —

Burroughs soon became disenchanted with the lot of junior enlisted men at Grant, whose chief duties amounted to what he ruefully referred to as ditch digging and “boulevard building.” This led to keen contempt for the post’s commanding officer Col. Edwin Vose Sumner, Jr. (son of Civil War Gen. Edwin Vose “Bull” Sumner). Of his commanding officer, Burroughs recalled: “Sumner was a very fat man who conducted regimental maneuvers from an army ambulance. It required nothing short of a derrick to hoist him onto a horse. He was then and is now my idea of the ultimate zero in cavalry officers.” Burroughs noticed considerable tension between many of the officers and enlisted men. He laid all blame for perceived low troop morale squarely on the post commandant’s shoulders.

In contrast, Burroughs had great respect for the Buffalo Soldiers he interacted with. “A couple of companies of the 24th Infantry, a colored regiment, were quartered at Grant at the time I was there. They were wonderful soldiers and as hard as nails… On several occasions I worked under colored sergeants, and without exception they were excellent men who took no advantage of their authority over us and on the whole were better to work under than our white sergeants.”

Army Life in Arizona

Situated near the southwestern slopes of the lofty Pinaleño range, Fort Grant boasted comfortable living quarters, a well-stocked commissary, even an artificial lake adjacent to Officers’ Row.

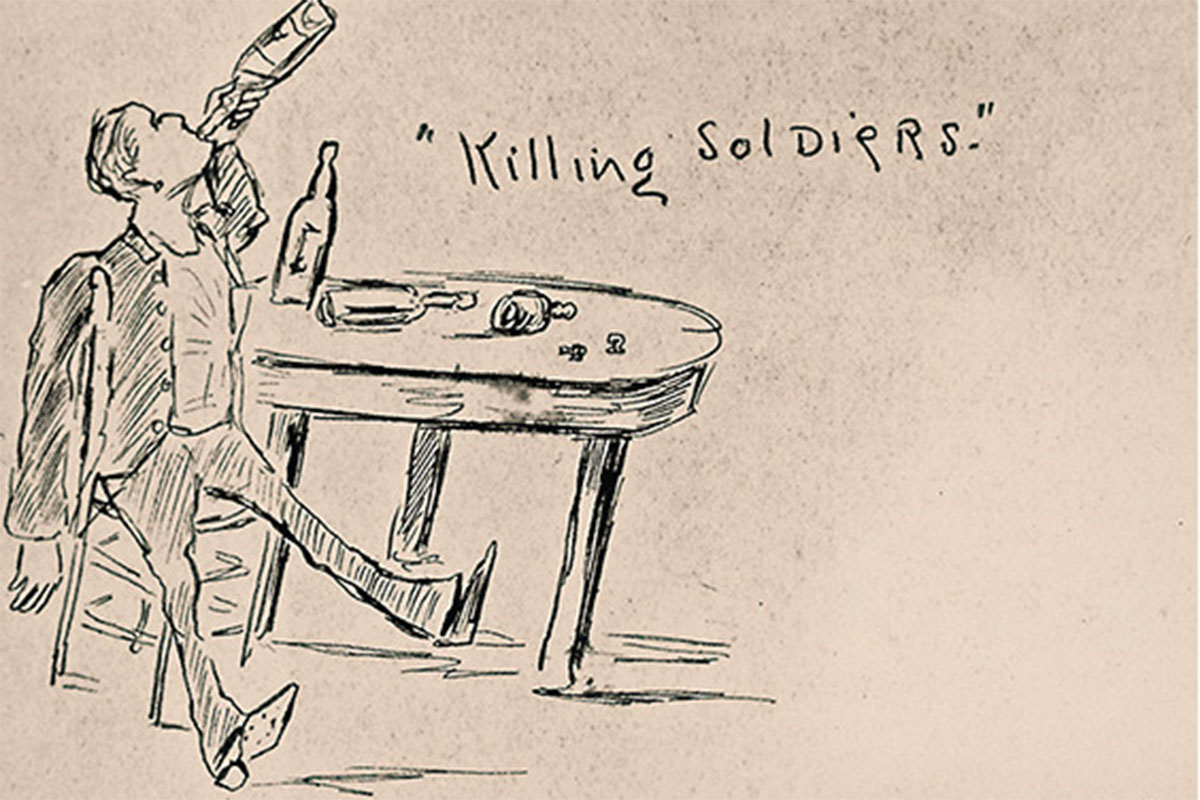

For relaxation soldiers could patronize the post canteen. Beyond that a motley collection of saloons, dance halls and gambling dens beckoned from nearby Bonita. Come payday a lonely trooper might visit the local bordello or “hog-ranch,” there to have his saddle-weary ashes hauled with the professional assistance of a soiled dove.

Fortunately, the future author of Tarzan and John Carter of Mars preferred to indulge his creative muse in his spare time. Burroughs enjoyed sketching scenes of post life, jotting down notes and impressions, and writing letters home. These creative efforts, combined with vivid memories, later inspired Burroughs to pen two insightful novels of the Apache Wars: The War Chief (1927) and Apache Devil (1933).

— Photo of Camp Grant Hospital Courtesy Sulphur Springs Valley Historical Society —

With the arrival of summer electrical storms, Burroughs noted, “The drinking water became impossible because of the rain and I presently achieved dysentery.” He soon landed in the post hospital where his sufferings continued unabated under the care of a pair of drunken medical officers and an abusive hospital steward. Burroughs recalled, “I was so weak that I could scarcely stand and they would not give me anything to eat …but castor oil.” He recalled being punished severely for attempting to devour an unauthorized crust of toast. He later wrote that “the most disagreeable part of my service at Fort Grant were my various contacts with the medical department.”

— Sketch of soldier by Edgar Rice Burroughts, Copyright Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. —

Relief came in a call to duty. Burroughs remembered: “There was always a lot of excitement at Fort Grant. The Apaches were corralled at another post not far distant [San Carlos Reservation] and there were constant rumors of another uprising similar to those led by old Geronimo. The Apache Kid and his band of renegades were giving trouble in the south… We were always expecting boots and saddles and praying for it.”

The Apache Kid

As Burroughs later recalled, a man and his daughter had been murdered on the Solomonville trail, and the Apache Kid’s band were the presumed perpetrators. In late August, B Troop was ordered out on scout to hunt for the Apache Kid. Still suffering with dysentery, Burroughs pleaded his way out of the hospital in order to ride with his troop. The ensuing journey followed a wagon trail “short cut” over the high crags of Mt. Graham. This became a hellish ordeal for Burroughs, who was literally falling out of his saddle most of the way. “All during this march I was carrying fourteen pounds of ammunition and weapons around my waist—a weight which did not greatly alleviate the intense abdominal pain I was suffering.” In the field several weeks, B troop was at times split into two-man patrols sent out in different directions. Years later, Burroughs observed: “As I look at it now, we were just bait.”

— True West Archives —

In his memoirs, Burroughs recounted an interesting anecdote about B Troop’s Apache scouts: “We went into camp on the Gila River, not far from Duncan, Arizona. We camped in a grove of large cottonwoods beneath a low cliff. Our Apache scouts camped at a little distance from us and nearer the cliff. At night, sometimes, we heard owls hooting at the top of the cliff and the call would be answered from the camp of our scouts. The old timers said that the renegades were communicating with our scouts and it was thus that they kept in touch with the movements of the troop.” Apaches feared owls above all creatures, believing them to be embodied spirits of dead relatives, so it is unlikely any Apache would communicate in this fashion. Burroughs’ anecdote is far more revealing in what it says about the older soldiers’ suspicions and distrust of the loyalties of Apache scouts.

Of Apache women Burroughs observed: “A never ending source of interest to me

were the Apache scouts and their families. We saw little or nothing of their women, though several that I did see among the younger ones were really beautiful. Their figures and carriages were magnificent and the utter contempt in which they held the white soldier was illuminating, to say the least.”

Birth of a Western Novelist

— Courtesy John Langellier —

B Troop never encountered Apache Kid or his band. But Burroughs found an important part of himself on the backbone of Dzil Nchaa Si An (“Big Seated Mountain,” the Apache name for Mt. Graham). Sick as he was, he probably should have remained at the fort. But had he done so he would have regretted that choice the rest of his life.

Diagnosed with a heart condition (which made receiving a commission impossible) Burroughs was discharged from the Army on March 23, 1897. Lt. “Tommy” Tompkins, whom Burroughs greatly admired, gave him an “excellent” character rating.

Burroughs’ legacy of frontier soldiering lives on in his two masterful Apache War novels written nearly a hundred years ago. Within their pages Geronimo, Juh, Cochise and Victorio live again, along with Shoz-Dijiji the Black Bear and his beloved Ish-kay-nay, Cibeque medicine man Nakay-do-klunni and others. Painstakingly researched, written from the heart, and daringly presented from the Apache point of view, The War Chief and Apache Devil contain all the love, hatred and pathos of human existence caught in the crucible of war.

A life member of The Burroughs Bibliophiles, Frank W. Puncer has collected, studied and written about the life and works of Edgar Rice Burroughs for 45 years. As a resident of Arizona, Puncer has a special interest in Burroughs’ Western novels.