In 1849, Joshua Abraham Norton, born in England around 1818, arrived in San Francisco, California, from South Africa with a $30,000 inheritance and dreams of business successes. Those dreams came true.

He developed not one but many successful ventures—a retail store selling gold-mining supplies, a cigar factory, a rice mill and real estate. By 1855, his fortune was estimated at more than a quarter of a million dollars.

But then came one disaster after another, and he stood to lose it all. He spent three years and most of his money trying to save his fortune. A hard-nosed banker named William T. Sherman, who would command greater fame during the Civil War, foreclosed the mortgages on Norton’s real estate holdings. A depression hit. His commodities inventories rotted. He failed in the stock market. He lost his friends among San Francisco’s elite. In 1858, he declared bankruptcy—and then suddenly, he disappeared.

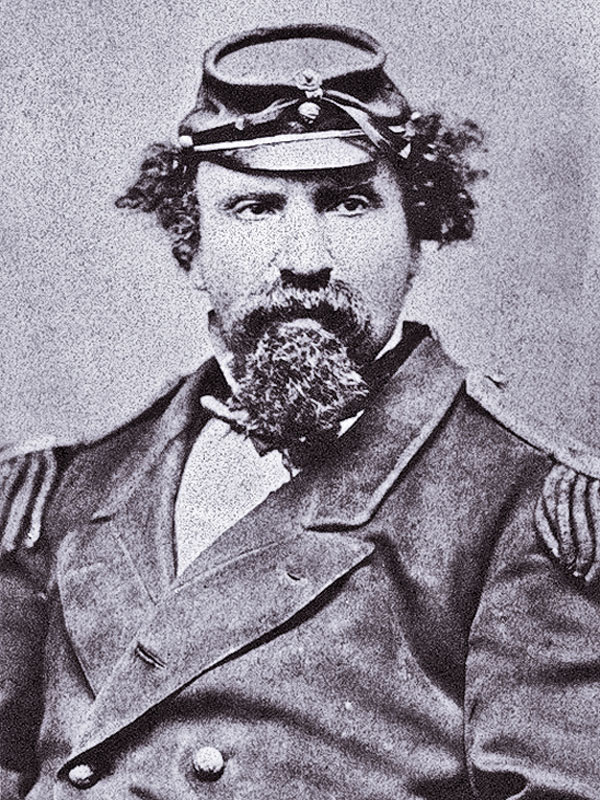

Nine months later, a disheveled stranger appeared in San Francisco. He wore a rumpled U.S. Army uniform, but carried himself with a royal demeanor. In 1859, he presented the San Francisco Bulletin editor the following notice, which he “respectfully requested” be placed in the next edition:

At the peremptory request of a large majority of the citizens of these United States, I, Joshua Norton, formerly of Algoa Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and now for the past nine years and ten months of San Francisco, California, declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these U.S.

Norton I, Emperor of the United States

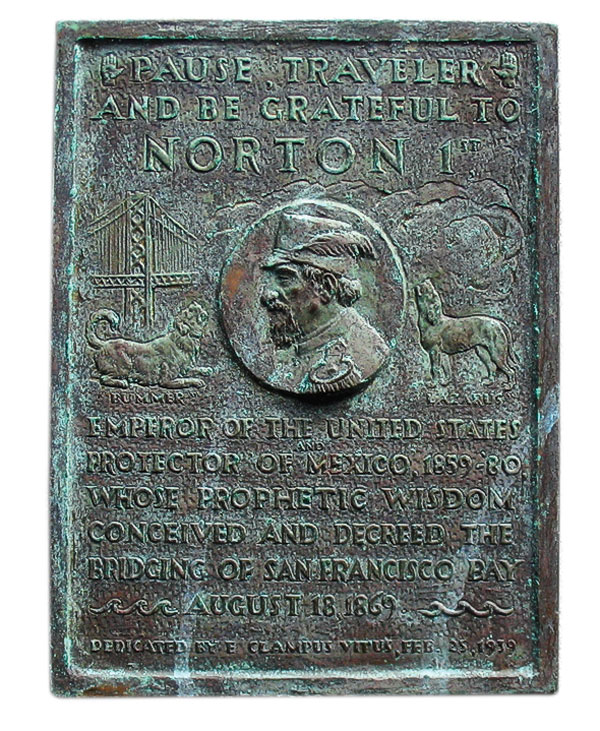

The editor ran the notice, thinking that it might increase newspaper sales. For the next 21 years, Norton I ruled as emperor, and the people of San Francisco received him as such, addressing him as “Your Majesty.” Businessmen gave him free meals and a special seat at public events. The California legislature always reserved a seat for him. He issued various proclamations, including ones abolishing Congress, firing U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and Confederate States President Jefferson Davis, and ordering construction of a bridge between Oakland and San Francisco. Newspapers printed his pronouncements. He even issued his own imperial currency. He conferred on loyal businesses the endorsement, “By appointment of Norton I, Suppliers for His Royal Majesty.”

On the evening of January 8, 1880, Norton I collapsed dead at the intersection of California Street and Dupont. Ten thousand mourners attended his funeral. The newspaper ran a banner headline: “Le Roi Est Mort” (The King is Dead).

But Emperor Norton I lives on. Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson wrote him into their novels, a plaque in San Francisco honors his prognostication of the bridge linking that city to Oakland. He was beloved in his day and is a tourist curiosity in ours. The King is dead. Long live the King.

Dennis Peterson is the author of Confederate Cabinet Departments and Secretaries. He lives in Taylors, South Carolina, and previously wrote American history textbooks for BJU Press and served as a senior technical editor at Lockheed Martin.