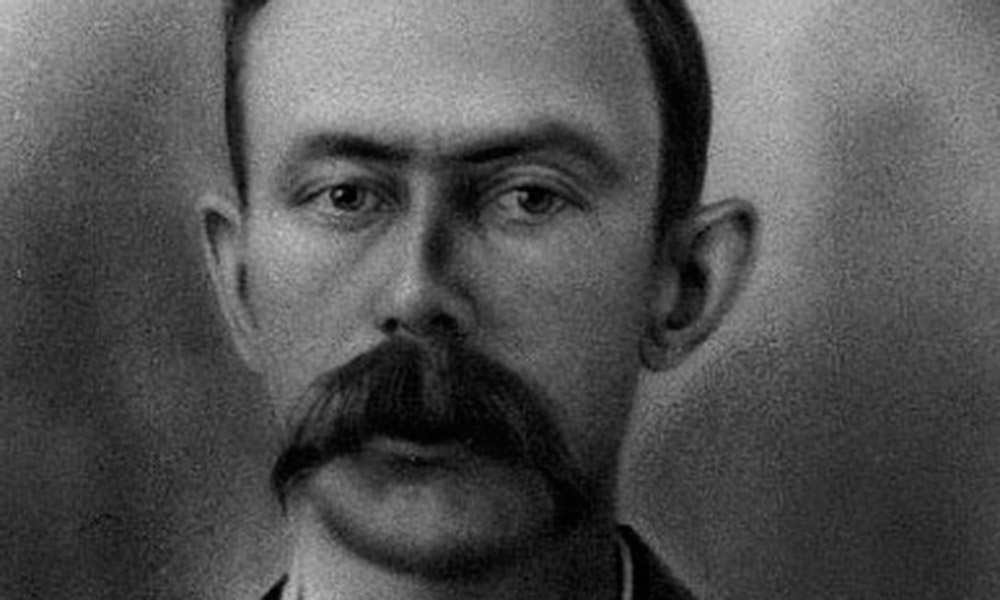

Irish immigrant Thomas Fitzpatrick signed on with William Ashley to head out West in search of beaver in 1823.

He traveled up the Missouri River, and from there he joined his fellow mountain-bound men in a confrontation with Arikaras. Surviving the fight, he continued on into central Wyoming and wintered in the Wind River Valley with Bible-toting mountain man Jedediah Smith.

The following spring, the men crossed South Pass—a break in the Rocky Mountains over which hundreds of thousands of emigrants would eventually cross—to trap in Green River country.

We will follow Fitzpatrick’s trail starting in eastern Wyoming, at Fort Laramie, which began as a fur trading post known as Fort William. This National Historic Site interprets four major eras in Western history: mountain men, American Indians, overland trail travelers and the frontier military. Fitzpatrick had a hand in all of them.

Guiding the Emigrants

Fitzpatrick, already well established in the mountain trade, came to Fort William bringing a supply of trade goods destined for the rendezvous in 1832. In 1841, he guided Belgian Jesuit Pierre DeSmet and emigrants west across Kansas and Nebraska, stopping at Fort Laramie to resupply before continuing over the route that would become the Oregon and California Trails. In the group headed to Oregon was Ezra Meeker, a man who, more than half a century later, would map and mark the Oregon Trail. Also in the party were California-bound John Bidwell and John Bartleson. All of the emigrants sought free land where they could forge better lives. They resupplied at Fort Laramie before traveling farther west.

Fitzpatrick was back at Fort Laramie many times in his life, including in 1851, when he took part in the first major treaty conference with Plains tribes. Roughly 10,000 members of the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Assiniboin, Gros-Ventre, Mandan, Crow and Arikara tribes agreed to allow roads—such as the routes to Oregon and California—to cross their lands. (The Shoshones, under Chief Washakie, came to the council but left after an attack against them by some Lakotas.)

From Fort Laramie, we will follow the route Fitzpatrick took with the 1841 emigrants by traveling west on U.S. 20-26 and I-25 to Casper. This is a good place for an overnight stay. I recommend staying at the Ramada Plaza Rivershore and eating a delicious meal at Poor Boys Steakhouse just down the street. Be sure to allow time to visit Fort Caspar and the National Historic Trail Interpretive Center, which focuses on the last crossing of the trails as the California (Oregon, California and Mormon) routes left the North Platte River here and struck out toward the Sweetwater Valley. Leaving Casper, toward Sweetwater, follow Highway 220 southwest to Independence Rock and then to Muddy Gap before turning northwest on U.S. 287.

As you enter the southern Wind River Valley near Lander (where Fitzpatrick spent his first winter in the West back in 1823-24), turn southwest on Highway 28 and cross South Pass. At Farson, stop at the recently-renovated Farson Merc for some ice cream before continuing west along the Oregon-California trail route by staying on Highway 28 to the junction with Highway 372, turn north there, then southwest on U.S. 189. Head west on U.S.30 to Montpelier, Idaho, where you can visit the National Oregon/California Trail Center. Tell my good friend Becky Smith, who manages this center, that I sent you.

When Fitzpatrick led the first party of emigrants through this area in 1841, he continued on to Fort Hall (you’ll find a replica of it at Pocatello, Idaho), but the Bidwell-Bartleson party struck out toward California. Fitzpatrick himself would later travel to California as a part of John C. Fremont’s second exploratory trip to the West in 1843-44.

From Montpelier, travel west on U.S. 30 then south on I-15 to Salt Lake City, Utah, and turn west on I-80 to Sacramento, California. This is country Fitzpatrick traveled through with Fremont.

The Mountain Trade

From Farson, drive northwest to Pinedale on U.S. 191, where a visit to the Museum of the Mountain Man is an absolute must. This is the area where six of the rendezvous took place between 1825 and 1840. At the museum, you can get directions to the site of the DeSmet monument, the location where the Jesuit celebrated the first mass in the Rockies.

From Pinedale, travel north to Jackson Hole, a place named for one of Fitzpatrick’s fellow trappers, David Jackson. This is a great place to spend a day or more, with plenty of lodging and dining options—for a hearty breakfast, try Jedediah’s House of Sourdough or the Bunnery.

Strike out west on Highway 22 over Teton Pass to Driggs, Idaho. Then head north on Highways 33 and 32 to Ashton and north on U.S. 20 to West Yellowstone, Montana. This route takes you through a region known in the 1800s as Pierre’s Hole.

In 1830, Fitzpatrick and fur trappers Jim Bridger, Milton Sublette, Henry Fraeb and Jean B. Gervais purchased the Rocky Mountain Fur Company from Jedediah Smith, David Jackson and William Sublette; Fitzpatrick became the head of the organization. (Later on, with Bridger, Sublette, Andrew Drips and Lucien Fontenelle, he formed Fontenelle, Fitzpatrick and Company.)

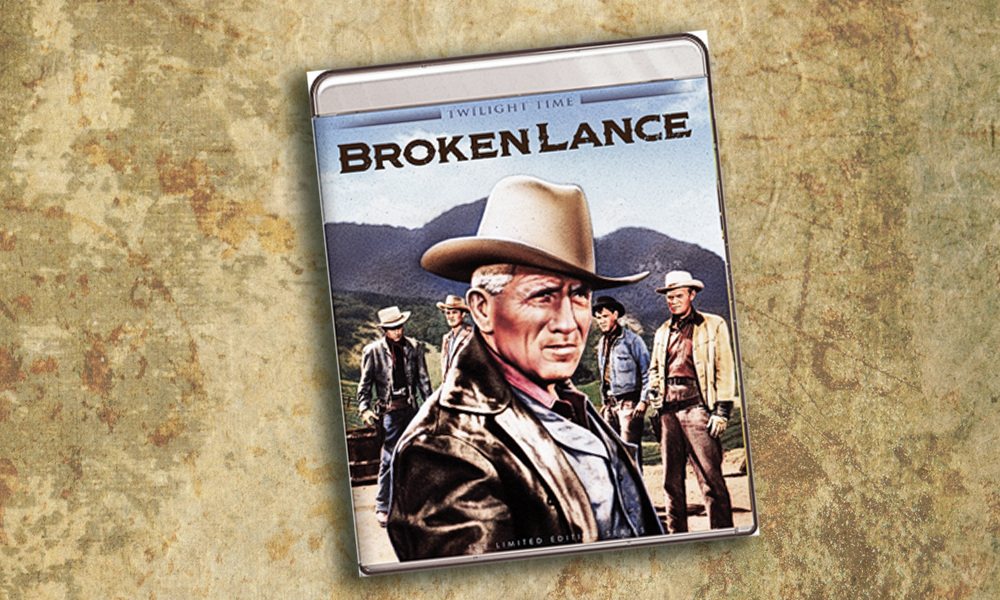

Fitzpatrick spent time trapping, hauling the plews to St. Louis, purchasing supplies and transporting them back to the Rockies for distribution at the annual rendezvous. In 1832, he was returning from St. Louis to the rendezvous in Pierre’s Hole when a harrowing encounter with some Gros Ventres left him struggling for his life. He managed to escape their wrath, but afterward, his hair turned grey and he became known as “White Hair.” Of course, Fitzpatrick had another—better known—mountain name, “Broken Hand,” given to him by the Indians after his hand was damaged by an exploding rifle.

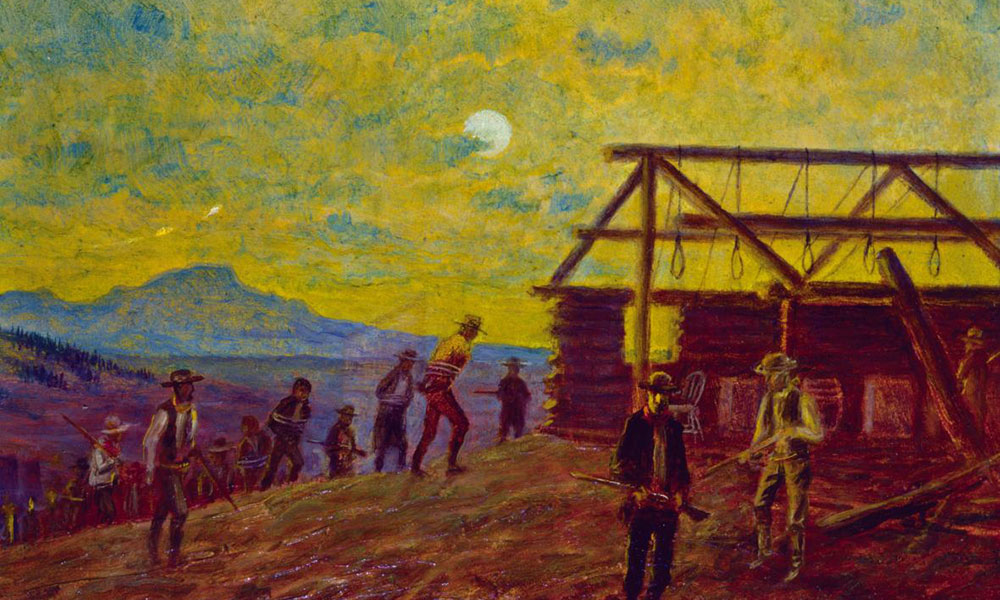

When he finally reached Pierre’s Hole, Fitzpatrick took a leadership role during a fight on July 18, 1832, that the mountain men had with area tribesmen.

Our route continues north from West Yellowstone on U.S. 287 to Three Forks, Montana, a region where Fitzpatrick more than once trapped after 1829, even though it was a risky area to be in due to the omnipresent possibility of attack by the then-hostile Blackfeet.

From Three Forks, travel east on I-90 to Livingston, a great place for an overnight stay or a good meal. Then turn south on U.S. 89 to Gardiner and enter Yellowstone National Park. This region and nearby Grand Teton National Park provide the most accessible opportunity to see wild country as Fitzpatrick would have seen it. Although there will be plenty of other visitors at the developed areas of Yellowstone—Mammoth, Canyon, Old Faithful and Lake Yellowstone—you can experience the backcountry by taking advantage of a Lodging and Learning experience in the park offered by Xanterra Parks and Resorts, where you will have guides who can show you wildlife from wolves to bears and explain geologic features in the park.

A stay in one of the east wing rooms at Old Faithful Inn will give you a 24-hour view of Old Faithful geyser; or you can kick back and relax in a quiet room at the Lake Hotel. You’ll find an excellent meal of salmon or buffalo at the Old Faithful Snow Lodge, and equally succulent fare at Old Faithful Inn Dining Room or Lake Hotel Dining Room (plan ahead, though, as you need reservations).

Continue south through the park and then take U.S. 26/287 to Dubois, Wyoming, and cross Wind River Basin to Lander. From here, we will retrace our route to Muddy Gap and then turn southwest to Rawlins before heading east on I-80 for 20 miles and turning south on Highways 130/230 to Saratoga and Encampment.

Fitzpatrick came into this country (my home territory) with John C. Fremont’s second expedition. They crossed the Continental Divide on June 13, 1844, when Fremont wrote, “With joy and exultation we saw ourselves once more on the top of the Rocky Mountains, and beheld a little stream taking its course towards the rising sun.”

Dropping down the east face of the Sierra Madre, the Fremont party saw the “valley of the Platte, with the pass of the Medicine Butte beyond, and some of the Sweet Water mountains; but a smoky haziness in the area entirely obscured the Wind River chain.” Here, Fremont’s party turned south toward “objects worthy to be explored,” namely the three parks of Colorado—North, Middle and South.

On June 14, the men tramped south along the east face of the Sierra Madre mountain range. “The country is beautifully watered,” wrote Fremont, adding, “In almost every hollow ran a clear, cool mountain stream; and in the course of the morning we crossed seventeen, several of them being large creeks, forty to fifty feet wide, with a swift current, and tolerably deep.” Antelope, elk and buffalo abounded. “We halted at noon on Potter’s fork—(the Encampment River)—a clear swift stream, forty yards wide, and in many places deep enough to swim our animals.”

They camped that night within a half-mile of where my house now sits. First thing in the morning, they chased and tried to lasso a grizzly bear. By midday, they had reached the North Platte River (traveling parallel to present-day Wyoming Highway 230) and found what the Arapahos called “The Door” and what Fremont referred to as a “gate” in the mountains, through which they passed to enter New Park, known to the Indians as “Cow Lodge” and which is today’s North Park, Colorado.

Drive through Walden and remain on route to Granby; then travel south on U.S. 40 to Empire before turning east on I-70 toward Golden. As my buddy Johnny D. Boggs well knows, I avoid driving in city traffic whenever possible, so I opt to skirt around the Denver metro area on C-470 and then head south on I-25 through Colorado Springs and Pueblo before turning east and traveling along the Arkansas River on U.S. 50 to La Junta and Bent’s Fort.

Along this route, I’ve dined at some good places to eat with Boggs. The first restaurant, I suggested: The Fort, near Morrison, which is pricey and fun (here you will find your whiskey laced with gunpowder, and I’m not kidding). The second, Johnny located: Bud’s Bar in Sedalia, which is small, noisy, inexpensive and has one thing on the menu: a hamburger and chips. As they say, at that price, fries aren’t part of the deal.

Fitzpatrick and Fremont actually traveled farther west, moving through North Park into Middle Park, and then crossing to the headwaters of the Arkansas River and through South Park, to places now marked by the towns of Buena Vista and Salida, before following the Arkansas out onto the plains and to Bent’s Fort.

Bent’s Old Fort

Fitzpatrick would see much of Bent’s Old Fort. He had come through on the Santa Fe Trail earlier in his mountain man career, hauling goods intended for the fur rendezvous in 1831, by first going to Santa Fe and Taos, New Mexico. Because of delays, however, no rendezvous took place that year. He returned to Bent’s Fort with Fremont in 1844 and subsequently guided Steven Watts Kearny and his Army of the West to the fort. Broken Hand remained with Kearny as he took his army to Santa Fe in 1845, but he did not return to California at the start of the Mexican-American War. Instead, he carried dispatches for Fremont to Washington, D.C., where, in 1846, he was appointed Indian agent for the Upper Platte and Arkansas Rivers. In that capacity, Fitzpatrick lived and worked at Bent’s Fort, having a small office in which to conduct business.

Today, the re-created fort has the small office furnished in a way that it may have been situated when he lived and worked there. Fitzpatrick held councils with the Cheyennes at the fort in 1847, and the following year, he met with the tribes who lived along the South Platte River, at Fort St. Vrain, one of four fur trade posts situated along the river. He unsuccessfully advocated the establishment of an agency to serve them on that tributary, but, as noted earlier, he did successfully broker the treaty conference at Fort Laramie in 1851.

Solid, dependable, fearless and trusted by Indians and whites alike, Thomas Fitzpatrick made a wide circle in his travels in the West from 1823 until his death in 1854, exploring the length of the Missouri, Platte and Arkansas Rivers on the Atlantic watershed, through the Great Basin, and into Oregon and California.