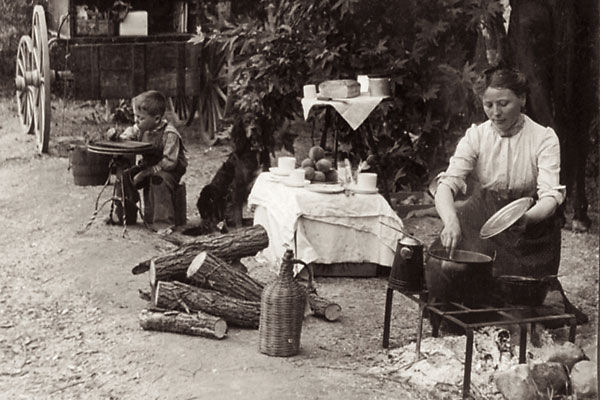

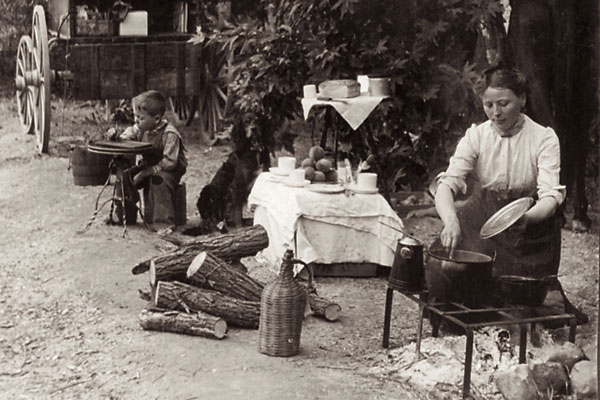

“Chris lifted the food box down from the front of our wagon, while Carrie built a fire in the Russian iron camp stove.

“Mother peeled potatoes and parsnips. Soon they were steaming in iron pots on the stove, along with some wild crab apples brought from home, and were simmering in the brass kettle. Mother made biscuits, which she baked in the oven of their wonderful new stove, and fried bacon, and prepared gravy,” wrote Catherine, as she traveled with her family through Idaho in 1864 on their way to Oregon.

Heading west was not a journey for the delicate, prissy or lazy. Everyone had responsibilities, and most pulled their weight. The journey could be fraught with dangers and hardships, but some pioneers enjoyed a trouble-free trek along the frontier. While on the trail, many ate on thick china plates, drank from matching cups and used knives, forks and spoons. Those who planned their trips well, and traveled with other wagons, generally made it to their destinations. Their memories of the food they ate were probably much like Catherine’s:

“How good it all smelled. How glad we were before the journey’s end for those china dishes and for the stove. The tin dishes used by many were very hard to keep right. With the stove, mother could stand up to cook instead of having to bend over a campfire with her face in the smoke. When I watched some of the other women, choking in the fumes of the fires, their backs bent until they must have felt ready to break, I often thought, ‘I’m glad my mother doesn’t have to cook that way.’ Our stove, too, burned very little wood, and on the treeless prairies, that was a great advantage.”

Not everyone chose to bring along a heavy cook stove. Some chose their weight to be in the form of additional supplies or food stuffs.

Sometimes cooking on a stove or over an open fire was not an option. When the threat of Indians reared its ugly head, or weather conditions were bad, the emigrants wisely refrained from starting campfires. When cooking fires were forbidden, the cooks made due with what they had. Leftovers—yes they even ate them 100 years ago—from previous meals, like cold boiled ham and an extra pan of biscuits from breakfast, sufficed.

Depending upon where the emigrants departed from, and where they camped, determined how the menu was planned. Some staple items included flour, sugar, salt, rice, beans, bacon, fresh and dried fruit, dried peas, coffee, lard and sorghum molasses. Biscuits, bread, hotcakes, stews and soups were just some of the morsels made from those staples.

The perishable supplies, like fruit and meat, gave out first. Yet wild game and berries were often found along the way: antelope, deer, quail, huckleberries, blackberries and raspberries. When fresh berries were harvested, the women used them in a variety of tasty ways; they made sauces, pies and cobblers.

As rations grew shorter, cooks got creative and made the most of what they had. Some meals were prepared by boiling an old ham bone to which liquid was added, and then boiled. The few scrapings from the last biscuit dough pan (likely made from the last measure of flour), both musty and sour, were mixed.

It’s hard to imagine making that journey today—just how many of us could handle it? Some might say those pioneers were crazy, but I like to think they were adventurous, courageous and ingenious!

As you make the biscuits, imagine being out in the middle of a prairie. Picture yourself baking biscuits with blowing wind stinging your face, hot fire embers popping and lifting a heavy cast Dutch oven….

Biscuits for Today’s Cook

4 c. flour

1 tsp. salt

3 tsp. baking powder

1 c. water

4 T. butter or shortening

1/2 c. milk

Mix the dry ingredients together in a large bowl. Cut the shortening into the flour with a pastry blender or two knives. Add the water and stir just to mix. Do not over beat the batter, because the biscuits will become tough. If the dough looks too dry, add more water. Roll the dough to a 1/4-inch thickness on heavily floured surface. Cut the biscuits with a biscuit cutter and place on a greased baking sheet. Bake at 425° for 10 minutes, or until done.

“A very good kind of family biscuit can be made in the same way as the bread, by using a less quantity and only adding a little shortening, either of butter or lard—a table-spoonful of lard, or two of butter, will be sufficient for as much dough as will make a large loaf of bread, and that will suffice for a family breakfast or supper.”

—Josiah T. Marshall in The Farmers and Emigrants Complete Guide, 1855