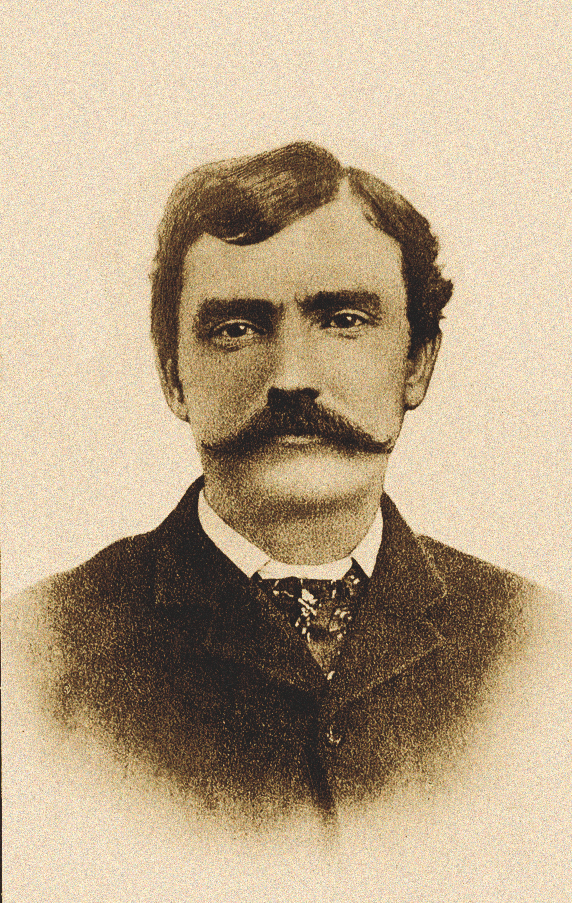

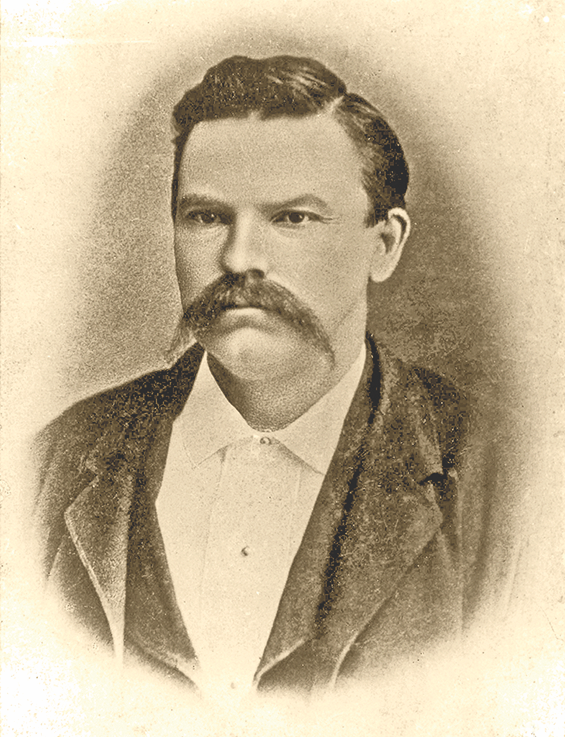

The Last Hours of the Notorious King Fisher

The hack delivered King Fisher and Ben Thompson to the Vaudeville Theatre within a few minutes, as it was not far from Turner’s Opera House. It would probably have been quicker to walk, but they had chosen to ride. They could not have realized it would be their last visit to the Vaudeville, where tragedy awaited them.

What neither King Fisher nor Thompson knew was that word of their arrival in San Antonio had been telegraphed to the proprietors of the Vaudeville, alerting the owners of their approaching visit. This telegram forewarned Joseph C. Foster and William H. Simms of their arrival. And United States Marshal Hal Gosling had ridden the same train as Fisher and Thompson and promptly after exiting the train, went to the Vaudeville, where he personally informed a theatre employee that Thompson had come down on the train and that they could expect trouble, as “there seemed to be h-ll in his neck.” Simms, now fully aware of the impending danger, chose to alert City Marshal Phillip Shardein, who stated that he would send over six police officers to prevent any difficulties.

All Photos Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted

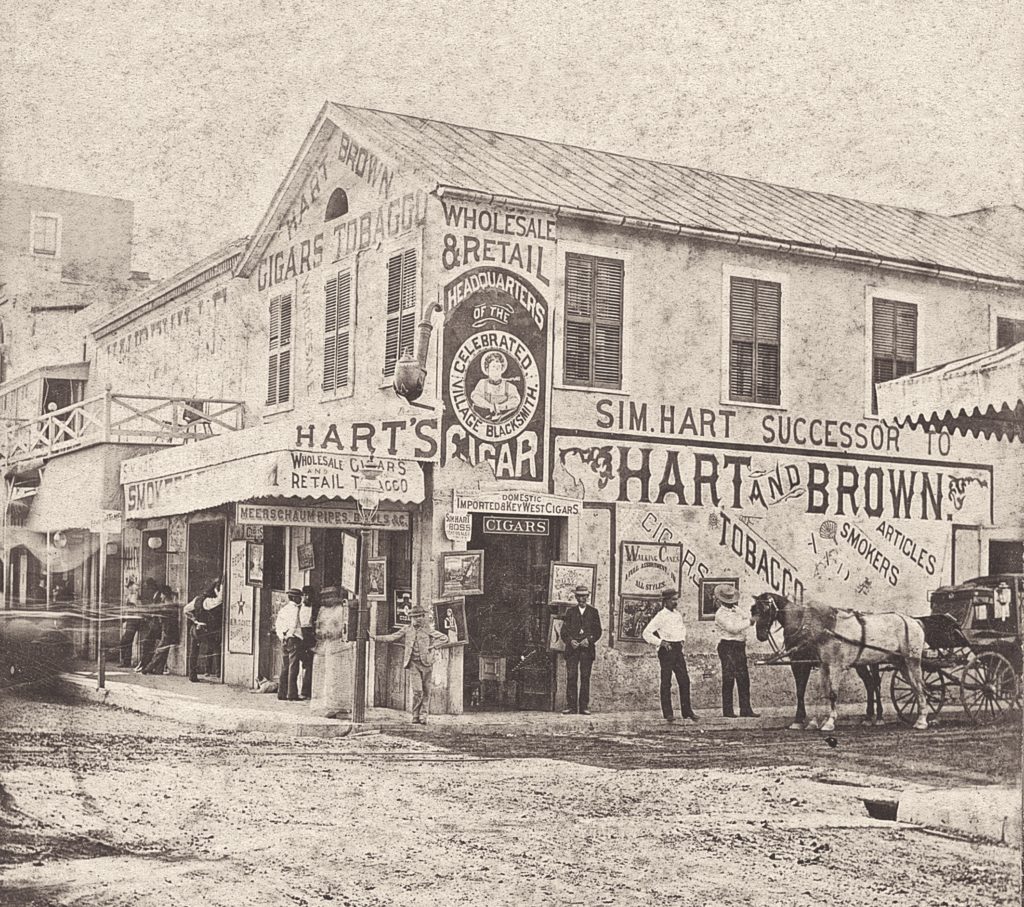

Having descended from their hack, Thompson and Fisher entered the Vaudeville. Ben, and possibly King as well, stopped at the bar for a drink. It is easy to imagine that Ben may have used this “opportunity” to let everyone know that he was back in town, he was not afraid to enter into the “den of infamy,” and he was ready for whatever fate could befall him. Before long, rather than staying at the bar, the pair went upstairs where a variety show was in progress. San Antonio historian Elton R. Cude wrote that Simms invited waitresses, or “girls in short skirts and red stockings,” to wait on them. Thompson consumed yet another drink while Fisher called for a cigar.

Later, at the coroner’s inquest, Simms and Vaude-ville house policeman Jacobo Santos Coy testified that as soon as the pair entered, Thompson made a threatening remark about Joe Foster, against whom he held an old grudge. Coy claimed he warned Ben to keep quiet. Then Joe Foster and William Simms came into the gallery, and Ben asked them to have a drink with him and Fisher. Drinks were ordered and in the ensuing conversation Ben made more threatening remarks against Foster, including calling him a thief. Foster told him to keep quiet, that he didn’t want a fuss. Thompson stated to his old enemy: “Foster, come downstairs.” Foster answered: “There is no need; I don’t want to have any difficulty with you.”

By now all had risen from their seats. Foster, Simms and Coy were standing near the door, with Thompson and Fisher to their right, about four feet apart. Coy interfered and told them to quiet down. Ben again called Foster a thief, adding, as the Austin Statesman wrote, an “opprobrious epithet” as he struck at him and tried to draw his pistol. Coy interfered, knocking the pistol down, which was a dangerous move as he could have easily been killed as a consequence. Then the shooting began.

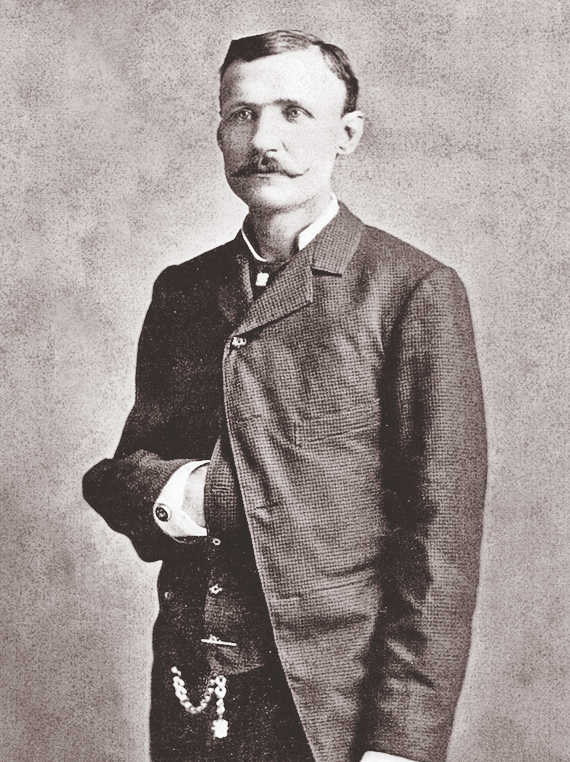

“It is impossible to say who fired the fatal bullets,” reported the Statesman. With the first shot, patrons rushed the doors, and several jumped out of the windows. A subsequent examination of King Fisher’s pistol found that, unlike the other guns, all of its chambers were still loaded, which means that he must have been shot first. “Thompson died shooting. Both he and Fisher died side by side, and the floor was flooded with their gore.” Foster was shot through the right leg, just below the knee, “and bled profusely.”

When the shooting stopped, people wanted to see the victims and tried to gain entrance to the building they had just vacated so hurriedly, but the doors were closed to all except officers and reporters. Justice Anton Adams was notified and quickly summoned a jury of inquest. J.M. Emerson was chosen as foreman of the jury and, after searching the bodies for wounds, presented the following conclusions: Ben Thompson had been shot once over the left eye, once in the left temple, with the ball coming out under the chin, and also through the abdomen and another spent ball inflicted a second wound over the left eye. King Fisher had been shot in the heart, the head just over his left eye and the right leg a few inches above the knee. According to the inquest, two of the deadliest gunfighters in Texas had been gunned down without taking a single adversary with them. Officer Coy had received “only a slight wound in the calf of his right leg.” Joe Foster had received a dangerous wound in his leg, which was self -inflicted when he attempted to pull his pistol. He was taken to his home, where he received medical attention.

City of Rumors

On the morning of March 12, the only conversation on the streets of San Antonio was the double killing at the Vaudeville. Many people believed that the killing of Ben Thompson and King Fisher was an act of premeditated murder, arguing that their deaths could only be accomplished by a carefully planned ambush. No one was arrested, although everyone knew who had been involved in the shooting. The idea was clearly expressed that some person, or persons, had laid a trap for Thompson and that a number of men had fired from ambush—that not only Simms, Coy and Foster were the shootists but there had been others as well. Rumors of all sorts were floated about the city. Joe Foster was suffering greatly from his wound, and the odds of surviving it were “as much against as in favor of his recovery.”

Courtesy True West Archives

The coroner’s findings were reported in the Statesman and later in other major newspapers: “That Ben Thompson and J. K. Fisher both came to their deaths on the 11th day of March, A.D. 1884, while at the Vaudeville theatre, in San Antonio, Texas, from the effects of pistol shot wounds from pistols held in and fired from the hands of J. C. Foster and Jacob S. Coy, and we further find that the said killing was justifiable and done in self-defense in the immediate danger of life.” This verdict, as reported in San Antonio’s Daily Express, was generally accepted in San Antonio, but in Austin, where people were shocked at the death of Thompson, many reacted differently, including the Statesman reporter himself. He clearly did not accept the findings of the coroner’s report and explained why: Thompson had ruled Austin, and the San Antonio police were determined that he would not rule their city as well; Thompson was of reckless courage and careless of human life when under the influence of alcohol, as he was that night; Thompson had killed Jack Harris, suggesting the possibility of revenge-seeking Vaudeville workers; the people in the Vaudeville did not like Thompson, and from the moment he entered the Vaudeville he was a doomed man. King Fisher, who perished with Thompson, was merely in the wrong place at the wrong time.

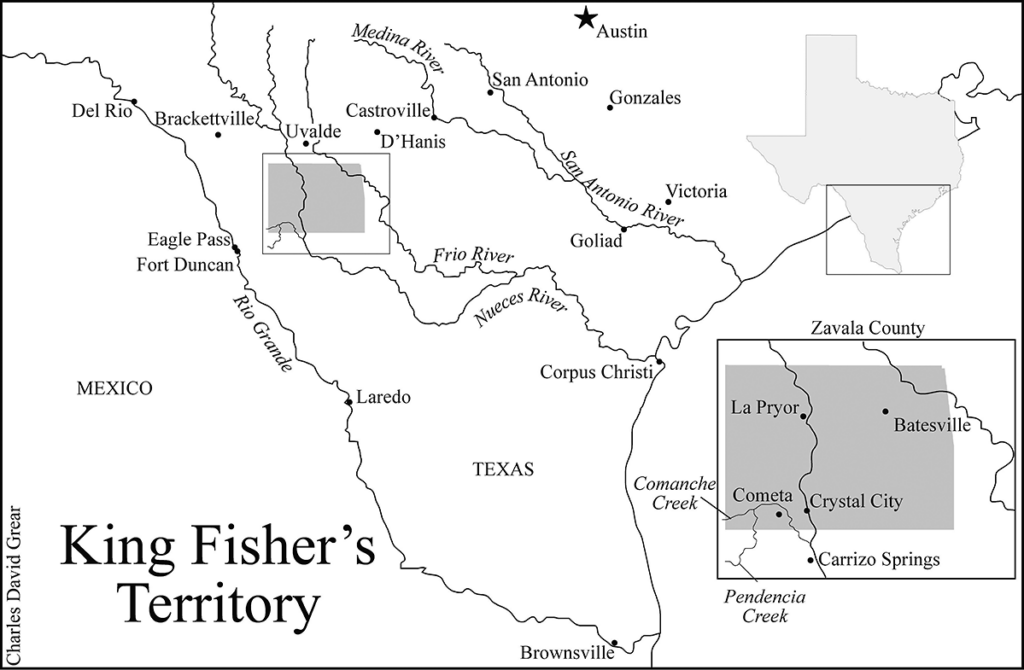

Map Courtesy of Charles David Grear

Wrong Place, Wrong Time

The shooting happened because Thompson had become involved in an altercation with the three men named: Foster, Simms and Coy. In the struggle Thompson and Coy went down together, with Coy holding Thompson’s pistol. For this reason, no one could possibly say who fired the shots. “It is believed that Thompson was killed by his own pistol in the hands of Coy,” concluded the reporter, going on to state that “Coy’s pistol was fully loaded and Fisher’s was found in the scabbard.” Thus the remaining pistols were those of Simms and Foster, not Coy.

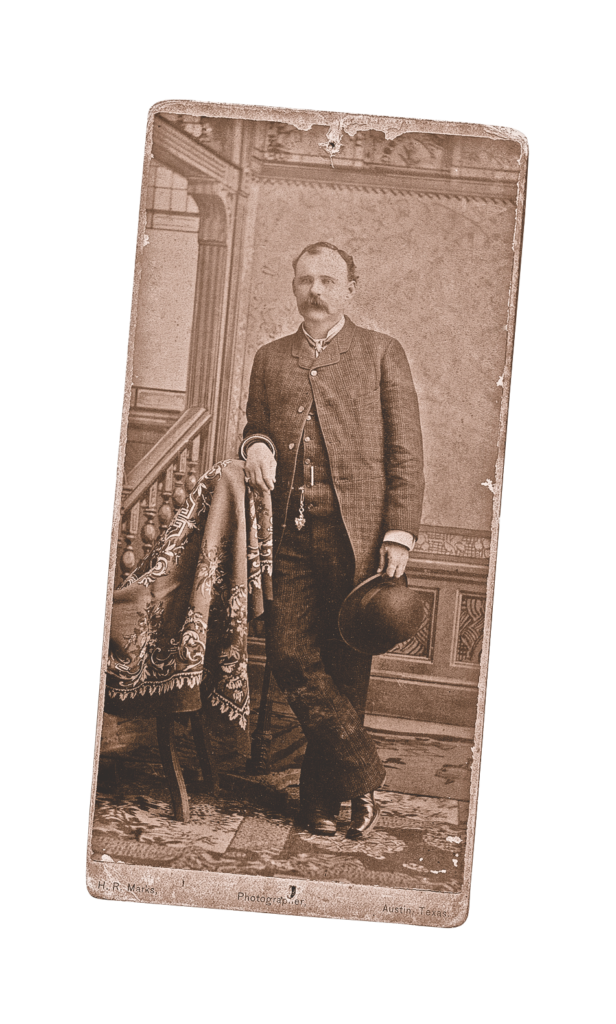

Due to the seriousness of Foster’s leg wound, he submitted to amputation, and it was reported that “he will in all probability die.” A bit of sympathy was also expressed for Thompson’s compatriot: “When the smoke cleared away Fisher was lying across his companion.” However, at least one reporter ignored the fact that Fisher was at the time of his death the acting sheriff of Uvalde County and identified him as “the incarnation of desperadoism.” Many, on the other hand, regretted Fisher’s death, as it was known that he had led a reformed life for the last two years “and hopes were entertained for his future.” The reporter from the Austin Weekly Statesman must have been among the latter, as he finished his lengthy report philosophically: “It is the irony of fate that men with the reputation for personal prowess possessed by the departed should be shot like dogs and butchered like sheep in the shambles, without one life in exchange for their own.”

Courtesy of Thomas C. Bicknell

The bodies of King Fisher and Ben Thompson remained on the floor of the upper stairs of the Vaudeville, bloodied from multiple bullet wounds, not only from pistols which Foster, Coy and Simms claimed were the cause of their deaths, but yet-to-be revealed bullets from Winchester rifles as well as additional pistols. The inquest performed in San Antonio, determined by many to have been perfunctory, would soon be challenged by the results of an inquest on the body of Thompson, which was performed in his own residence. The forensic evidence proved Thompson was not shot by the men standing before him, instead he was riddled by bullets that originated from above and from slightly behind him. Thompson never saw the men who cut him down.

Courtesy of Thomas C. Bicknell

No inquest was performed on the body of King Fisher. His body was placed on the 6:40 Sunset train by Deputy U.S. Marshal Fred Niggli, who, with several other friends, accompanied the body to Uvalde, where it arrived the night of March 12. Details regarding the transportation of the remains from the depot to the Fisher home remain unclear. Perhaps it is true that Marvin Powe, a young boy, was sent on horseback to the Fisher home to inform Sarah that she was now a widow. Among the letters in the Hobart Papers is one written by Powell Roberts of Santa Rita, New Mexico, to J. Marvin Hunter. “Mr. Marvin Powe,” Roberts wrote, “the present City Marshal of Silver City, New Mexico, was an eleven-year-old boy living in Uvalde when Ben Thompson and King Fisher were killed in San Antonio, and Powe carried the telegram several miles out to Fisher’s wife informing her of his death.” The body lay in state at his home where it was viewed by a great many of his friends and general citizens. The funeral took place at 4:00 p.m. on March 13, the largest ever held in Uvalde. Rev. J. W. Stovall of the Methodist Episcopal Church conducted the services.

Epilogue

Since it was boldly stated that Fisher and Thompson had been murdered, it would make sense to wonder whether any vigilantes attempted to deliver frontier justice to avenge their deaths. Lynch law was not a thing of the past, as every citizen and law officer knew. A brief item in the Austin Daily Statesman suggested that these concerns were a reality: It is said by parties from San Antonio, that letters have been received from King Fisher’s friends to the effect that unless the law is permitted to deal out justice to King Fisher’s murderers, they will be taken care of. Parties in Austin who knew Fisher’s followers are certain the murder of him and Thompson is but the beginning of serious tragedies sure to follow.

But there were no such “serious tragedies” following the Vaudeville killings. It is doubtful that any friend of Fisher seriously intended to determine who these murderers were and then deliver mob law justice to them. Enough good citizens of Uvalde did meet and sign a testimonial to King Fisher, suggesting what most people believed that King Fisher had “accomplished as much for law and order within the last two and a half years as any man in Western Texas, and this assertion will be verified by all officers who may have been thrown in contact with him.” This testimonial, which was printed in full in the San Antonio Daily Express, was in reaction to how the Express had earlier sullied the good name of Fisher. The Express had described both Fisher and Thompson as “desperate men, a terror in the neighborhood in which each resided, and if they are regretted at all it will not be by the law-abiding element of the state.” These were the Express editor’s true feelings, and of course he had a perfect right to say so. Fortunately for him and the newspaper, the good citizens of Uvalde did not storm the Express offices to wreck or burn but thoughtfully prepared their reaction to what they felt was unfair and gathered citizens to sign it. The memorial was signed by 271 citizens of Uvalde and vicinity.

Editor’s Note: Chuck Parsons and Thomas C. Bicknell’s “Into the Den of Infamy: The Last Hours of the Notorious King Fisher” is an exclusive excerpt from their book, King Fisher: The Short Life and Elusive Legend of a Texas Desperado (University of North Texas Press).

Chuck Parsons, a retired high school principal, has loved the Old West since boyhood. His biographies of Texas Ranger L.H. McNelly, gambler Phil Coe, John Wesley Hardin, Jack Helm and now King Fisher provide a true gallery of gunfighters.

Thomas C. Bicknell, born and raised in Chicago, developed a love of America’s Wild West at an early age. With co-author Chuck Parsons, King Fisher is his second biography published by University of North Texas Press.

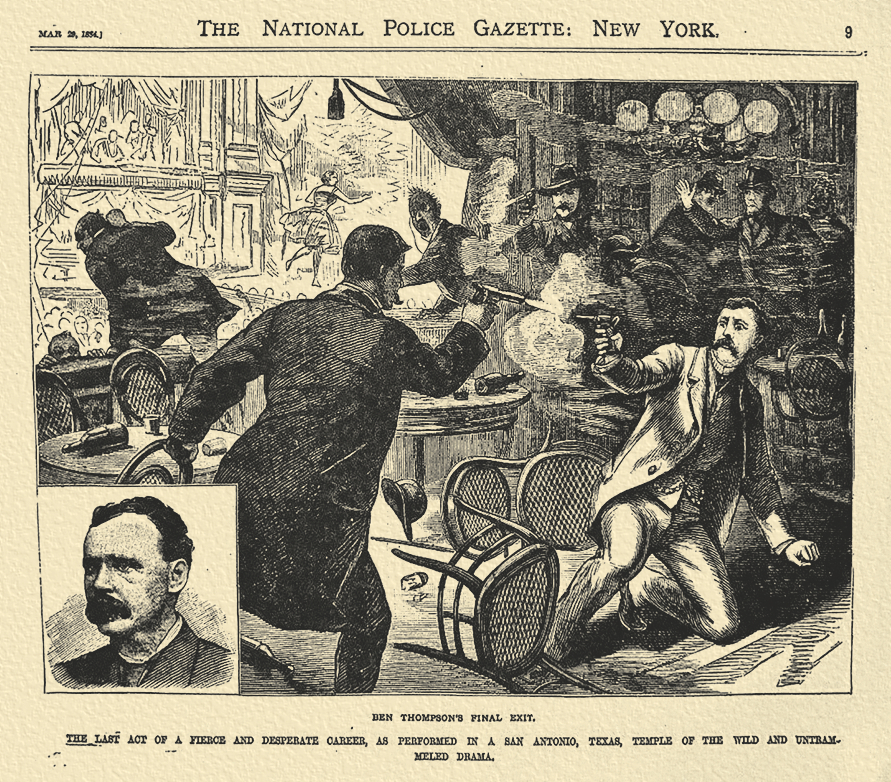

March 20, 1884, “National Police Gazette,”

Courtesy of Thomas C. Bicknell