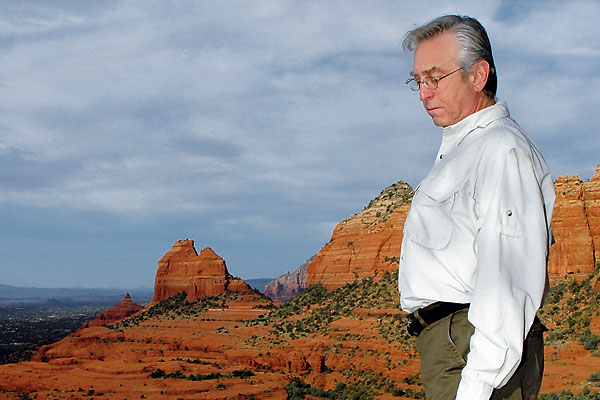

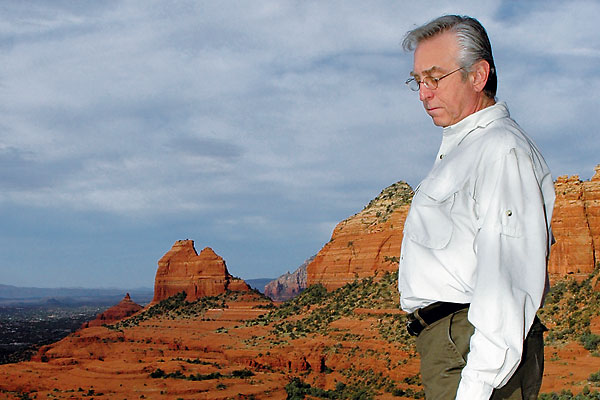

I first became interested in the history of Western film after moving to Sedona, Arizona, in 2001. My interest in Westerns jump-started when I could look out my window and see the sites of numerous cinematic stagecoach robberies and gun battles. I’m originally from Brooklyn, and I was used to seeing real crime scenes.

For 30 years I worked in art direction for publications, such as Cue (the first city magazine, later merged with New York magazine), and for companies like Penthouse and CMP Media. Now my day job is as creative director and part owner of Sedona Monthly magazine.

When I moved to Arizona I couldn’t get over the bright sunlight. I used to wear Ray-Bans to look cool. Now I wear them to keep from stepping off buttes.

I had not realized, before beginning to research Arizona’s Little Hollywood, how Sedona’s amazing film history had been neglected by most of the world but trivialized at home to puff up egos and real estate sales. Sedona suffered for it because the truth is far more compelling than the fiction.

The greatest Western star you’ve never heard of is Fred Thomson. He starred in 1928’s Kit Carson, the first Western with scenes shot in the Sedona area. By 1928, he was the movies’ number two box office draw, just behind Tom Mix. Unfortunately, Kit Carson turned out to be Thomson’s last movie––he died shortly after completing it––and little of his film output still exists. Old-timers who saw Thomson in his prime still speak his name with hushed reverence.

John Ford wasn’t the first director to use Monument Valley; it was George B. Seitz, who shot sequences for Zane Grey’s The Vanishing American there in 1925. Seitz was back in Monument Valley in 1938, filming exteriors for an Andy Hardy picture (Out West with the Hardys) just five weeks before Ford first laid eyes on the place while scouting locations for 1939’s Stagecoach.

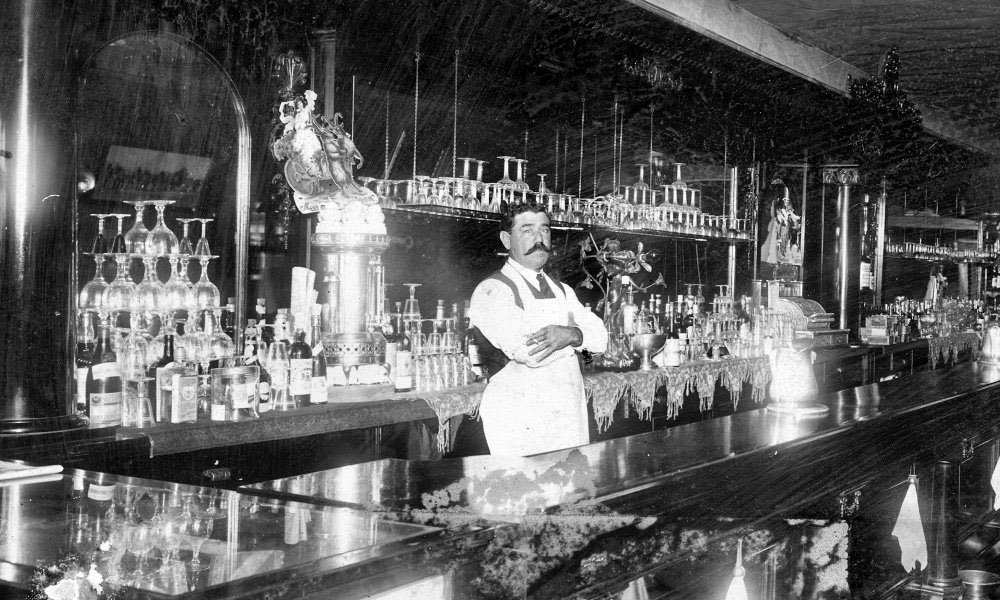

Zane Grey made quite a bit of money off of Hollywood, but he developed a seething dislike of the sharpies that ran the studios. “I will not say that all of the people in the motion picture industry are crooks,” he told a newspaper in 1927, “but I will say that all the crooks in Hollywood are in the motion picture industry.”

Nobody knows me like my wife Deb. She never stopped supporting me during the seven years of obsessive research it took to write Arizona’s Little Hollywood. Not once did she urge me to “hurry up and finish,” although I suspect she thought I’d never actually be done with it.

Don’t get me started on the mathematical formulations of quantum mechanics and electrodynamics. I’ll chew your ears off for hours.

After all this time, my favorite Western is still the 1931 version of Riders of the Purple Sage. I’m not just saying that because one of its chase scenes was filmed behind my house.

The greatest resource to me has been the Cline Library at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff. It’s a gold mine of Arizona history. Without the Cline I would never have unearthed the fact that a Nazi propaganda Western, Der Kaiser von Kalifornien, was partly filmed in Sedona in 1935.

History has taught me that modern technology isn’t as innovative as people think. Wide screen movies and Technicolor date back to silent movies. Half a century before Avatar, 3-D cameras were photographing the Sedona landscape in the third dimension for Gun Fury, a Raoul Walsh-directed Western.

Joe McNeill, Author

Starting in 2003, Joe McNeill authored 45 articles on local moviemaking for the arts-and-entertainment magazine Sedona Monthly, and it is these pieces that form the basis of his book, Arizona’s Little Hollywood: Sedona and Northern Arizona’s Forgotten Film History, 1923-1973. He is currently spearheading the creation of a museum in Sedona, Arizona, to preserve her film legacy.