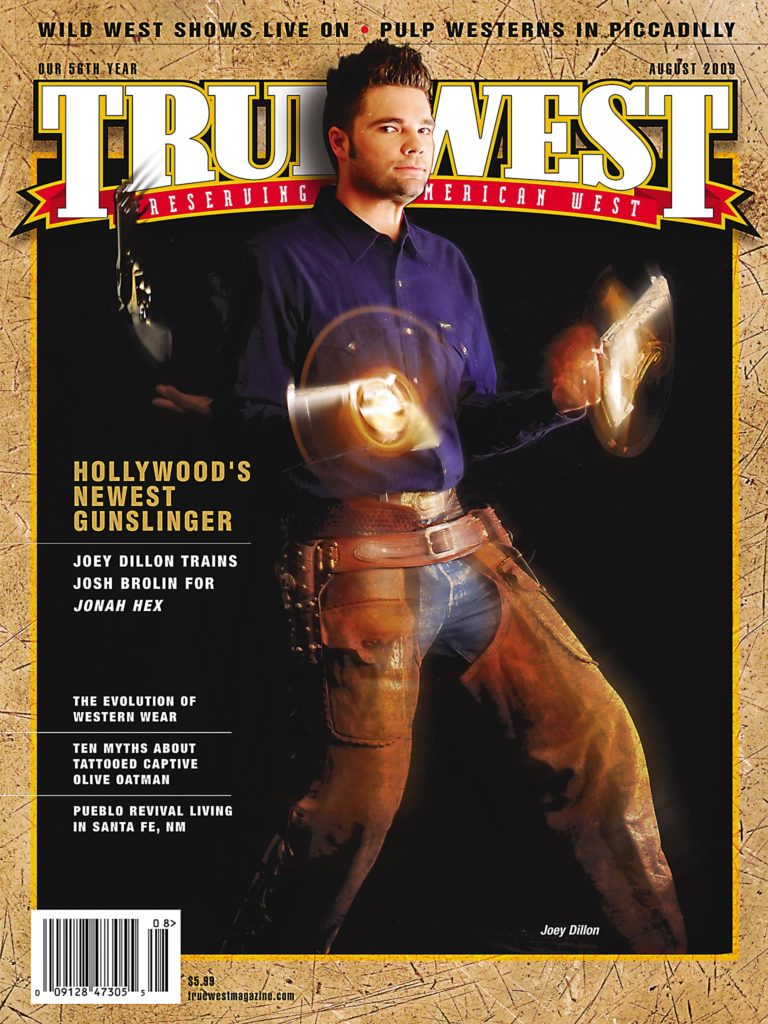

“Rocketshoes!” says Josh Brolin with a huge grin, as soon as I mention Joey Dillon’s name.

“He’s unbelievable. He’s the fastest thing I’ve ever seen.”

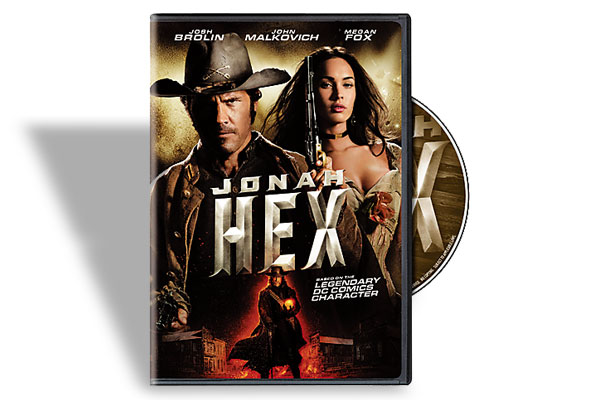

Joey Dillon, a.k.a. Rocketshoes, teaches men like Brolin how to look good with their guns. In Brolin’s case, that’s important, because the actor is starring in the film adaptation of DC Comics’ Jonah Hex (due out in summer 2010), and Hex is a 19th-century bounty hunter who lives by the gun.

“I had already done three years on a Western series, so I knew a lot of spins and all that, but he took me further,” says Brolin, who played James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok in the ABC series The Young Riders. Hickok was said to have been pretty good with his guns, so Brolin was far from being an amateur when Dillon was brought aboard. “We spent two or three days together just working through things, and he taught me truly how to draw in a way I didn’t know,” Brolin says.

Some doubted, initially, whether Dillon could be of much use on the film. “Some people said, ‘I’ve read the script, and I don’t see that much gunhandling in this, but it’s Josh’s call, that he wants some training,’” Brolin says.

Dillon told the doubters, “It’s not just about spinning the gun around and cocking it, or spinning into the holster. But you want [Jonah Hex] to do everything as though he’s been doing it all his life. Otherwise you won’t buy that he’s good with his guns.”

The two trained at the Warner Brothers backlot, once home to The Waltons. At the first meeting, Dillon brought with him 14 guns. “I held up a Colt Walker—about as big as it gets—and I said, “You may move up to this in a few days, but for the next few days we’re just going to work with this—then I held out the derringer,” Dillon says. “I had welded a little ring on it for spinning and a fanny hammer, and I handed him the gun. He was like, immediately, ‘Okay, okay,’ dead serious. I had to tell him I was joking.

“And then I started busting out some of my tricks, which he liked. I have one where I throw the gun up in a backward spin, and I balance the barrel on my palm. It took him a couple of tries, but he did it right off. I told him, ‘You’re light years ahead of anybody else I’ve been teaching in the acting world.’ So we were able to go straight to the double-shot stuff, some of the different spins and some bad ass stuff, which he was eating up.”

Dillon, obviously, is fun to talk to, likely because showmanship is paramount in his work; he studied acting and performed stand-up comedy long before he ever applied those skills to his gunspinning.

“I grew up and graduated in a class with 14 other kids, in Don Pedro, California, which is out in 49er country. It was natural for me to get into the history of the West, learn how to ride horses and shoot guns, with my dad.”

Why did Dillon leave Don Pedro behind to move to Chicago? “I always loved making people laugh, always had funny skits and ideas in my head. I was thinking, ‘Where do talent scouts look for talent? They scout in Los Angeles, New York theatre, Second City in Chicago.’ Well I was born in the Chicago area, I have relatives there, and so I was thinking that if I failed, I wouldn’t be out on the street.

“I went from listening to crickets and coyotes as I slept at night straight to the inner city of Chicago. I was a bellman right next to the Sears Tower, and there were fire engines [driving by] every night. I had to sleep with headphones cause I wasn’t used to all the noise.”

In Chicago, Dillon was forced to make a serious career choice, as he measured his own acting talent against those of the people he worked with in class. “I realized, I’m decent at it, people like me, but there’s so many people in front of me who are better at it. When you choose a career, you need to know if God has really blessed you with that ability. Improv was fun, but I’m not like these guys, and they’re going to get way ahead of me.”

Dillon switched to stand-up comedy because he could assemble his routines more precisely. Structure and innate mechanical skills are two of his most important underlying talents. “I thought that with stand up I could pre-write my routines,” he says. “Then I started bringing in stupid inventions as part of the act.”

Fate took a hand when a relative was widowed not far from Donley’s Wild West Town in Union, Illinois. “I was always interested in the West, and I was a closet gunspinner. When my relative offered to let me live out there for free, I decided to audition at this Wild West Show.

“I didn’t have an act, just spun guns there like an idiot. Then they said, ‘We’ll pay you to do it.’ I thought, ‘I can do stand up at open mikes for free, or I can get paid to be in front of a crowd.’ So I worked there for a couple of years, falling off buildings, doing the stunt shows, being a comedic idiot, and then I’d change clothes and go do the gunspinning to music.

“It wasn’t long before I realized that there were gunhandling competitions. I decided I wanted to go out and find the best gunspinner. In the standard Wild West way, you find the guy who has the reputation; if you kill him, you get the reputation. So I had to spend a few competitions studying Bob Hamm, who is a terrific, excellent gunspinner, was nice to me and showed me a few things. I got good enough to where he was a little bit worried. After a while I did beat him, and the rest is history.”

Dillon is a two-time, world champion six-gun handler. Where Dillon differs from many in that field is his background as an entertainer. “When I started, I joined a re-enactment group. They would perform a skit and then push me out there and say, ‘Spin a gun.’ It took me a lot of years to put my stand-up comedy and my personality to use—instead of being some stoic type—you know, like [putting on] a gambler or bad guy persona.

“I’m a little goofy; I’m not slapstick. I even have a few props, but the shows I do when I’m not doing film and choreography is me, my personality. Yeah, I happen to be a world champion gunspinner, and that’s what you booked, but you’re buying a personality. I realized that was the key, because at a lot of these events, the guy who’s watching might be into guns, but his wife and kids are gonna want to leave. In order to get somebody to stick around for a half hour of gunspinning, you need to be entertaining.”

While Dillon tours as a gunspinner, he’s also been inching ever closer to a career in film. Acting is the dream. Coaching is the path. Westerns are the genre. “I think everybody is wanting to make a Western,” he says. “I want to champion the cause for the next generation. Eastwood, Wayne, Costner, that’s the direction for me, to introduce Westerns to a new generation.

“I’m 30 now, and I have one foot in the youth market, and one foot in being taken seriously, finally, as an adult. It took a long time for people to stop looking at me as some kid playing with guns, to get that respect. It’s nice to have that “3,” that age in my resume, because people think I look younger than I am. Being older, officially, seems to put people at ease, people who are considering hiring me to coach and teach for movies. It helps if they’re assured that I’m not a kid who might accidentally shoot their star.”

So how did this former “kid” get his nickname Rocketshoes? “When I was about 18 I took some metal header flanges, about four inches long, that resembled the rear of a rocket, flared out at the back, and I made some metal straps and screwed each to the outside of a shoe. The round pipe flange was a perfect fit for three “D” model rocket engines for each shoe. I ran wires up my leg to a handheld ignition battery pack. The idea was to run faster. I knew the faster I would run, the more I would be kicking my heels toward my butt. So I put some metal plates in my rear pockets, just in case I would burn through my pants back there. Well, it worked well. Every time I lifted a leg, it was wanting to shoot forward. However, those rockets are only good for a couple seconds. So if your foot race is longer than that, the added weight was actually not advantageous. My right shoe and sock caught fire, but someone standing by with a hose put it out. Ever since, my name has been Joey Rocketshoes. I officially changed my middle name to Rocketshoes.”

He adds, “I was going to change my last name, but the wife didn’t want to be Mrs. Rocketshoes. Oh well.”

Now Dillon spends his time modifying guns so actors like Brolin can perform with them more effectively. But first, he must select the proper weapons.

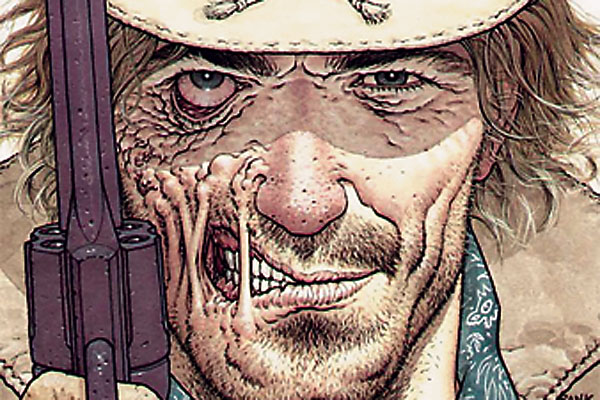

In the case of Jonah Hex, who first appeared in 1972, the character is most often seen handling Civil War-era handguns: Walkers, Dragoons and so forth. “When I discussed that with Brolin, we realized that there were a lot of variations in his guns, because the story had been reborn so many times, with different artists,” Dillon says. “Some of the guns kind of look like Remingtons, some are definitely Colt Peacemakers and a few of them look like 51 Navy’s. The Dragoons weren’t all over the place, but they were there enough, so we got four guns to cover our bases. Hex has got a set of Dragoons on his saddle holsters, and he carries two different guns on his hips. I know he uses a Peacemaker on one side, with a 7½ barrel; then I went with a ’58 Remington cartridge conversion, with an eight-inch barrel, on the other.

“I set up the guns with the help of Keith Walters, the prop master and armorer. We went to my sponsor, Cimarron Firearms, so all the guns they use in the film will come back to me. There’s six Dragoons, and I took all the bluing off—they have a real cool steel look to ’em—and then Josh has got the Remington and the Peacemaker, and a backup for each of those.

“Josh wanted to have the appearance of having a different gun on each hip, so it looked like he just grabbed guns from people as he went along, a collection of stuff he’s picked up off bodies or who knows what. He loved the idea of the Dragoons, when he’s doing the big heroic horse-riding shots, having those huge guns to fire from the saddle.

“I did some more work on the hammers. The Remington’s hammers are kind of small, so I cut it and welded about a half-inch extension right in the center to bring the hammer up to that of the Colt. The Colt hammer I heated and bent forward a little bit, so there was more of a spur to grab with his thumb when he spun it around—a good modification for the quickdraw, because he was really big into learning the quickdraw.”

Brolin is proud of his new expertise, and the price he’s paid for it. “I’ve jammed pretty much every finger I’ve got, making this movie,” he admits, “and I got the calluses.”

Dillon is equally proud of Brolin’s progress. “Well, he’s spinning long barrels, which is a pretty cool deal in itself, since that’s a little more weight to have to throw around. The Peacemakers are 7½-inch barrels, and the Remington is an octagonal barrel that measures out at eight inches. He did a lot of practicing with my prop guns, which are 5½ inches, before he went to the longer ones.”

What seems to have impressed Brolin the most, however, is Dillon’s composure and general demeanor. “As I said, he’s the fastest thing I’ve ever seen. But he’s humble—not an ass—he has no attitude, and we got along brilliantly.”

Dillon is currently in talks to participate in the film version of the comic series Caliber, which is a re-setting of Arthurian legend in the Old West. The author of the comic is Sam Sarkar, who is also the director of development at Johnny Depp’s production company Infinitum Nihil. Dillon adds, “After months of e-mailing, I finally got together with Sam, who had been researching me and seen some of my work. He seems interested in me as a teacher, maybe more, if the comic becomes a movie.”

If Dillon seems to be a little too sweet to be a world champion gunslinger, and a quick trip to YouTube will show you some of those skills, remember that gunslinging—twirling, flipping, tossing, catching (and holstering), cocking and firing—is as much about guns as basketball is about the ball or painting about the brushes. What Rocketshoes does, and teaches others to do, is a combination of art, athleticism and applied science; it’s all about finessing physics—but with a little stand up.

Skills of his sort have sometimes been seen as suspect. In an episode of Sam Peckinpah’s The Westerner, a young visitor has to be constantly reminded to stop twirling his guns, and his hubris finally gets him killed. In Tombstone, Doc Holliday and Johnny Ringo paw at each other, first with some Latin, and then with Holliday mocking Ringo’s gun twirling skills, using a tin cup. But who can forget how effective John Wayne was when he used simple spins to punctuate his words and actions? A perfect example of this is when Wayne shoots the eyes out of a dead Comanche in The Searchers.

“Wayne didn’t do much twirling,” says Dillon, “but when he did, it was expressive and not for the sake of showing off. It was just enough to make you or his enemy do a double take and say, ‘Whoa….’

“Reminds me of a time my wife and I visited Old Tucson Studios. We watched the stunt show, and when they needed a volunteer, they chose me. I tried to say no, but that never works. They held up a single action and asked if I had ever shot one before. I mentioned I had ‘a little bit.’ They wanted me to hold it out, cocked and ready, toward another actor. When I saw him go for his gun, he would beat me with his shot before I could pull the trigger. I wanted to just start doing over the shoulders and flat spins and go nuts, but it was not my show, and I took a respectful path.

“Well they asked me to say goodbye to my wife in the audience, and when I turned to say it, the other guy took advantage of my looking away to shoot at me. When I later handed the gun over, I did a little spin and reversed the gun, putting the handle into the waiting hand of the cowboy actor. It was not much, but it was fast, and just enough for him to break character and mumble ‘Whoa….’ John Wayne’s gunhandling sometimes gave that impression to his character. There was more beneath the surface, and you had to figure out if you wanted to risk seeing it.”