– Photos Courtesy Robert M. Utley Unless Otherwise Noted. –

In 2019 I turned 90. As a Custer aficionado since the age of 12, I was prompted to reflect on my connection with Custer and the Custer Battlefield, now termed the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Errol Flynn in They Died with Their Boots On (1942) introduced me to Custer. Captain E.S. Luce, superintendent of the Custer Battlefield National Monument, introduced me to the battlefield. In 1946, I bought a bus ticket, and from my Indiana home, toured the West. At Custer Battlefield, Luce, an old cavalryman, guided me over the battlefield. The following year, he twisted government rules to hire me, at age 17, as a seasonal ranger-historian at the battlefield. I spent six college summers telling tourists the story of the Little Bighorn.

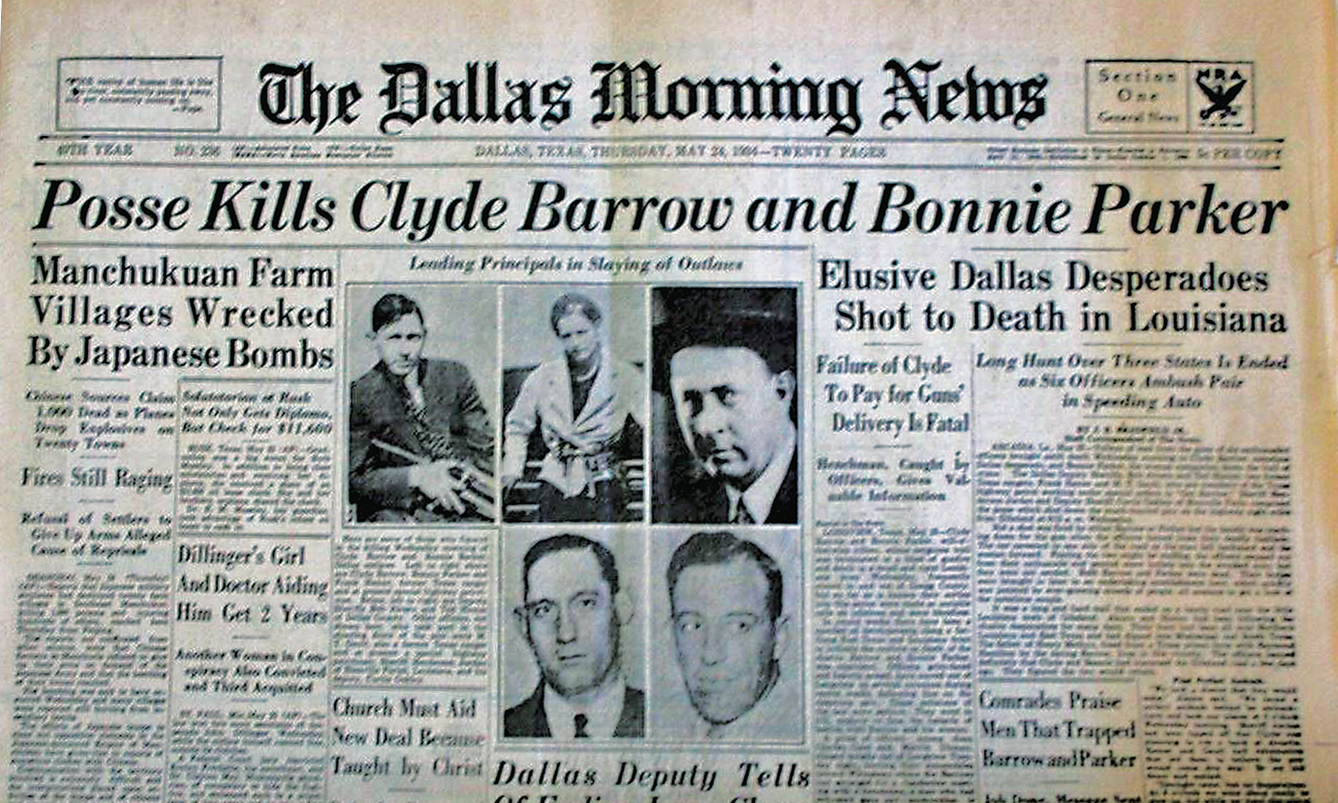

– True West Archives. –

Flynn and Luce may have introduced me to Custer and the Custer Battlefield, but Charlie Windolph made the connection personal. I can now look back over 72 years to meeting and visiting with Charlie Windolph, who 71 years earlier had fought in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. He was 97 and the last survivor of the troopers who fought there.

It happened this way:

During my first summer at the battlefield, in 1947, I met and became friends with R.G. Cartwright, athletic director at the Lead High School in South Dakota. He spent part of his summers combing the battlefield in the never-ending quest to discover what happened there. “Cartie” invited me to visit him in Lead on my way back to Indiana at the end of the summer.

A Trailways bus deposited me in Lead in mid-September 1947. Cartie toured me around the Black Hills as well as Lead and adjacent Deadwood. As the climax to my visit, he arranged for me to meet his longtime friend, Charlie Windolph. A German immigrant in 1870, Charlie had joined the cavalry to learn English. As a private in Company H, 7th Cavalry, he had found himself surrounded by Sioux Indians on the heights above the Little Bighorn River on June 25, 1876.

In 1947, long-retired from Lead’s Homestake gold mine, Charlie passed his time sitting in a rocking chair on the front porch of the home of his daughter, who cared for him. There he sat on a bright autumn day when Cartie and I ascended his porch. He received us warmly and invited us to sit on adjacent chairs. He was an old man, but he was still clear-minded, articulate and full of memories. He poured forth stories of the Little Bighorn that he had doubtless told to countless visitors for many years.

Before any stories, and throughout his stories, he dealt with his company commander, Capt. Frederick W. Benteen. Charlie worshipped Benteen. He could not heap enough praise on him as an officer and a company commander. “I thought he was about the finest-looking soldier I had ever seen. He had bright eyes and a ruddy face, and he had a great thatch of iron-gray hair. It made him look mighty handsome.”

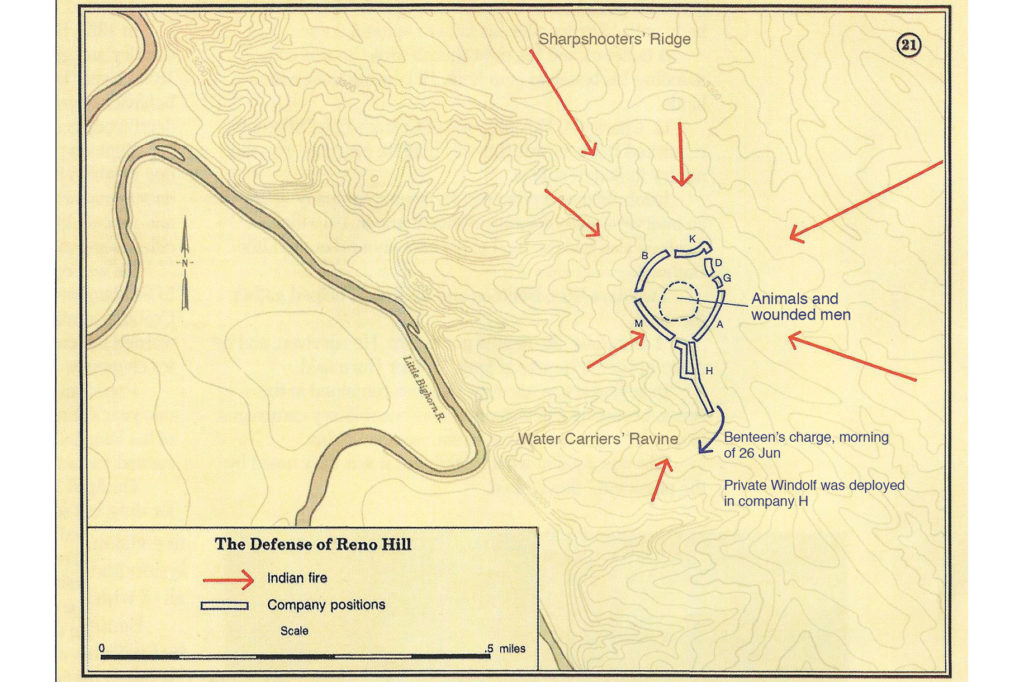

At the Little Bighorn, Windolph fought on Reno Hill with Maj. Marcus A. Reno commanding. Company H was one of the seven companies, together with the pack train, that were corralled on a bluff above the river. They did not know what had become of Custer and the other five companies, but they did know that Sioux warriors surrounded them and kept up a steady fire. From hastily scooped-out rifle pits and from behind packs from the mule supply train, they fired back for three hours until nightfall.

– Map of Reno Hill Courtesy True West Archives. –

The firing resumed at dawn on June 26. A bullet killed the trooper who shared Charlie’s shallow trench. Another grazed Charlie’s chest, then another shattered the stock of his Springfield carbine. He thought a particular Indian had singled him out for a target and concentrated his fire, now with his dead companion’s carbine, on that warrior.

Windolph described for me how Benteen strode along his company line oblivious to the bullets pinging around him. Charlie said he remonstrated with his captain for exposing himself, only to be commanded: “Windolph, get up here and look at all those Indians.” He did stand beside his captain, he said, though only momentarily.

– Courtesy True West Archives. –

The afternoon was beastly hot, and the canteens ran dry. The wounded began to cry for water. The only water was in the river below the rugged bluffs, and warriors hid in the brush along the riverbank, firing up at the troops. Major Reno commanded, but he was at the other side of the circle, so Benteen called for volunteers to go for water. Charlie was one of the 17 who volunteered. Benteen assigned him and three other marksmen to stand on the edge of the bluff and draw the Indian fire away from the men descending the ravine to the river. None of them was hit, although several of the water-carriers were. (They all were awarded Medals of Honor.)

Later in the day, Benteen saw warriors assembling below for an assault. He formed his company, Charlie included, charged down the ravine and broke up the forming Indian line. Shortly afterward, Benteen had Charlie Windolph stand at attention and awarded him a battlefield promotion to sergeant.

As twilight approached, the Sioux withdrew, packed up their lodges and moved south up the valley. They had spotted the troops of Gen. Alfred Terry and Col. John Gibbon, and the next day they learned from them that Custer and his five companies had been wiped out five miles down the river.

All these stories Charlie Windolph recounted for me on that September day in 1947. He had recently told them to the journalists Frazier and Robert Hunt, who published them that year under the title I Fought with Custer. I had not read the book when I sat, enchanted, and listened to the old man tell his stories. That half hour 72 years ago remains a cherished memory.

Charlie Windolph died on March 11, 1950, at the age of 99, the last white survivor of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. That summer, again working at the Custer Battlefield, I rode a bus down to Lead and returned with Charlie’s Medal of Honor, Purple Heart and discharge papers signed by Captain Benteen. They are displayed in the battlefield museum.

Author’s Note:

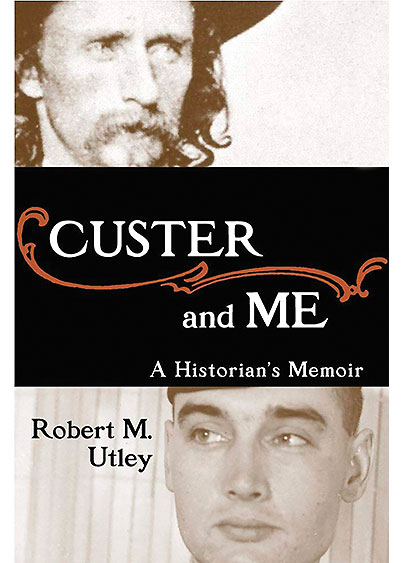

In 2004 I published a memoir titled Custer and Me. Errol Flynn, in They Died with Their Boots On had laid the groundwork for my rise to a Custer aficionado. At 90, I am led to look back on a memorable experience that links me over a century and a half to the battle in which Custer lost his life.