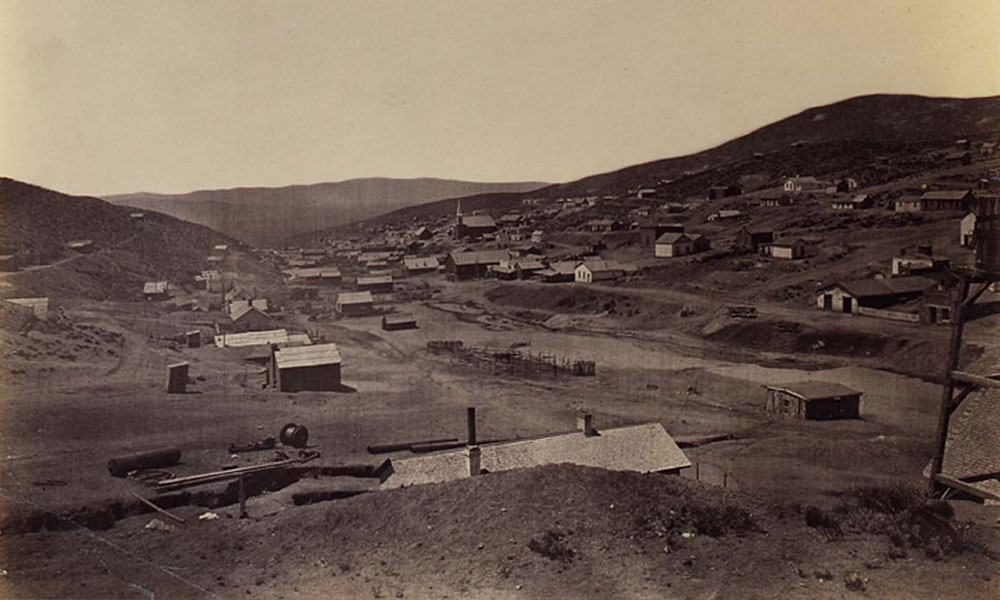

— Courtesy Mike Siegel Collection —

In the early 1970s, Hollywood filmmakers were leaving the studio back lots of Los Angeles with fresh screenplays in hand, actors under contract and movie crews in tow into America’s urban landscapes, rural backcountry and the small towns of the heartland. They were seeking a realism that could not be recreated on a soundstage, the light, sounds and physicality of the locations, and most important, the real people and places that had inspired the screenwriter’s words.

— Courtesy Mike Siegel Collection —

Over Labor Day weekend in September 1970, my father Jeb Rosebrook received a call from his agent Mike Wise. “Robert Redford wants a rodeo story. Do you have one?” Wise asked. Little did he know that my dad had just written a first draft of a story, “Bonner,” about an aging rodeo star whose career, family and hometown are all on the line. His agent also didn’t know that the highly personal story about my father’s adopted hometown, written after a short visit back to Prescott for the rodeo and the Fourth of July, would change the fates of so many, so quickly—especially our family.

My father, who first came to Prescott as a 9-year-old boarding student to attend the nearby Orme School in early 1945, had not been to Prescott since 1955, and the changes he witnessed driving into the historic Yavapai County seat from Cordes Junction through Mayer, Humboldt, Dewey and Prescott Valley made a strong impression on him, especially the development of the wide-open spaces of the Fain Ranch.

The “Bonner” story and the Junior Bonner screenplay that developed under the tutelage of producer Joe Wizan reflected my father’s love of Prescott and Yavapai County, its history, culture and people. A novelist before turning to screenwriting, he imbued his scripts with rich detail, lean, warm dialogue and history. Always history. And his words inspired Wizan to take the script to actor Steve McQueen and director Sam Peckinpah, both of whom signed up to participate in the production almost immediately. And they all wanted to make the movie in Prescott and Yavapai County. The reasons were many and personal why McQueen and Peckinpah wanted to leave the confining nature of film production in Hollywood, but most important, they wanted to produce the film on location in Arizona in the real-time of Prescott’s Frontier Days Parade and the World’s Oldest Rodeo. And in the summer of 1971, Peckinpah, McQueen and Rosebrook—disparate individuals united in purpose on location by producer Wizan—came to Prescott and left with a piece of history on film.

Junior Bonner was not the only rodeo picture of 1972 (Redford’s call for a rodeo story was definitely influential across Hollywood), but it can be argued that it is the greatest rodeo movie ever made in Arizona, about Arizona and Arizonans. Underneath—like the film—it is a deeply personal homage to family, historic Prescott and the small towns and ranchlands of Yavapai County. One reason the film was successful—and remains such a snapshot in time and history—was its location manager, the local Arizona Film Commission representative, president of the Fair Association and the Prescott Jaycees Rodeo Chairman, William Pierce. The local businessman was well-connected, friend to all and was not intimidated by Peckinpah or overly in awe of McQueen (he drove the star around on his motorcycle to get to locations during the parade sequence). Pierce recognized the locations my dad wrote about in the script and he was able to open all the doors to secure all the film’s locations. Pierce’s contribution to making the film a reality were so appreciated by the production company that the film ends with a heartfelt message of special thanks to Pierce.

Through my father’s words from the screenplay and in excerpts from his memoir, Junior Bonner: The Making of a Classic with Steve McQueen and Sam Peckinpah in the Summer of 1971, he takes the reader on a journey that honors Prescott and Yavapai County’s Old West heritage, past and present. And as my father told a Daily Courier reporter in 2008, “I wrote this movie for Prescott.”

The Courthouse Plaza, Downtown Prescott and the Frontier Days Parade

In Junior Bonner, the Yavapai County Courthouse Plaza and downtown Prescott are featured extensively throughout the script and film. Prescott was founded in 1864 as the Territorial Capital of Arizona, and the World’s Oldest Rodeo debuted on July 4, 1888, as did the parade. During the production of Junior Bonner, location manager and rodeo chairman Bill Pierce had the enormous responsibility of coordinating with the film company the filming of the Frontier Days Parade live as it happened, with numerous cameras on the rooftops of businesses on Montezuma, Gurley, Cortez and Goodwin streets. Pierce remembers all the building owners were cooperative, but the film crew “had to use generators as a lot of upper floors [of the historic buildings on the Plaza] were vacant.”

Fourth of July parades, as we all know, are very much a part of our national pride and fabric. Prescott and its iconic, historic town plaza are sewn into that fabric. As five cameras rolled, bands marched and played, clowns and Shriners paraded, the legendary Bill Williams Mountain Men rode horseback, Grand Marshall Casey Tibbs doffed his hat (showing no effects of his horse fall), and more bands played. There were the Orme campers, and young campers from nearby Friendly Pines Camp in a horse-driven stagecoach and, sure, enough, there came Curly Bonner’s real estate Reata Rancheros float, with hot pants “Dudettes” riding in back, watched over by Curly’s wife, Ruth (Mary Murphy), and Joe Don offering the crowd the gifts of hard candy.

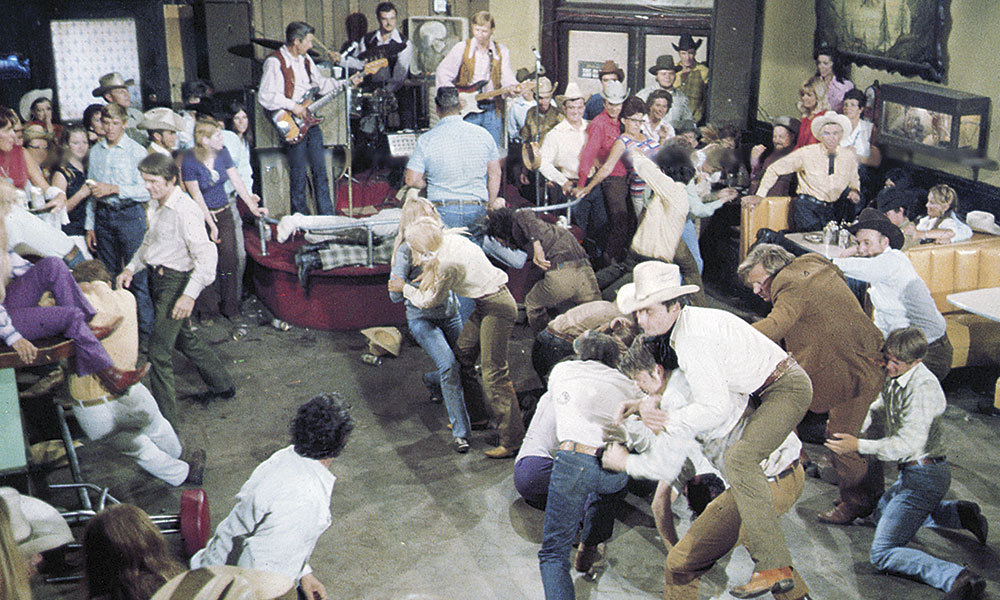

The Palace Bar and Whiskey Row

The Palace Bar, known today as the Palace Restaurant and Saloon, has been a central gathering place on Montezuma Street, aka Whiskey Row, across from the Yavapai County Courthouse and Plaza since it first opened as the Cabinet Saloon in 1874.

In Junior Bonner, the Palace Bar, had center stage. Director Sam Peckinpah made one of the upstairs rooms his office and bedroom (he also had a house rented for him and his family in town) and the Palace Bar became a centerpiece of the film’s locations in Prescott, most notably the rodeo dance, barroom brawl and love scenes between Steve McQueen and Barbara Leigh, and Robert Preston and Ida Lupino. According to location manager Bill Pierce, the film company was so grateful to Palace owner Shell (Sheldon) Dunbar that “after the movie was done the production company had McQueen’s Cadillac restored and gave it to him in appreciation of all his hospitality during filming and after hours.”

The production meeting: Jim Pratt needed a break in the budget. It would be extremely expensive to film the day rodeo, and bullriding-at-night rodeo, …

Two changes: we simply have our rodeo announcer tell the crowd they will take a break, similar to halftime in football, go down to the Palace, where we will have the truly all-hell-breaking-loose fight, then return to the rodeo for the final afternoon events, the last of which is Junior and Sunshine.

I wonder how rodeo purists will handle such a move. In my mind, there had never been a professional rodeo where the audience took a break, went off to drink and dance, then return to the remainder of the rodeo—all in one afternoon!

Bottom line: to stay on budget, this is the way it will be done.

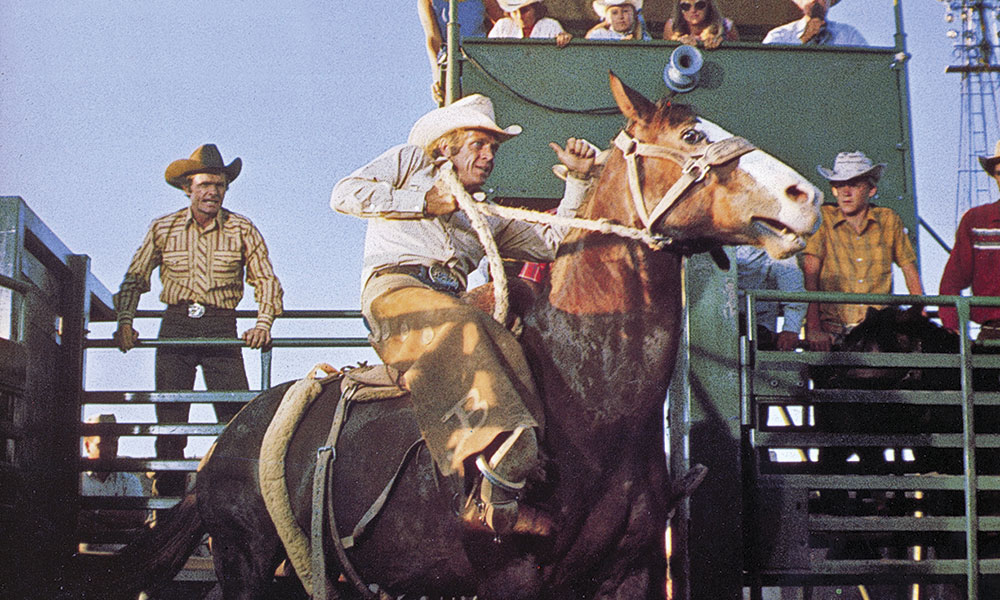

The Fairgrounds, the Homestead, a Bull and the Rodeo

While the World’s Oldest Rodeo had its first competition in Prescott in 1888, the Yavapai County Fairgrounds featured in Junior Bonner was not built until the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps funded and built it in the 1930s. Luckily for the production team, the location manager, Bill Pierce, was also the Prescott Jaycees rodeo chairman and the local Arizona Film Commission representative. The film crew had access to the arena throughout the rodeo and when the horses were not running at Prescott Downs.

In my original screenplay, working with Joe Wizan, the initial scene did not introduce Junior but his father, Ace, and his dog, Dougal, as bulldozers move in to demolish the old Bonner homestead.

For Sam, this action, the destruction of the family homestead, could come later. He wanted the action of man-against-animal to open the film, as Junior attempts the eight-second ride on a bull named Sunshine. Junior does not make the eight seconds. He is thrown off, nearly trampled, and badly hurt. Dramatically, this played into Junior’s need to face the challenge of riding Sunshine again, and, importantly, to do it in front of his hometown folks. …

So now an angry, if not terrifying, Brahma bull will open Junior Bonner.

— Courtesy NARA, ca. 1918 —

The Train Station

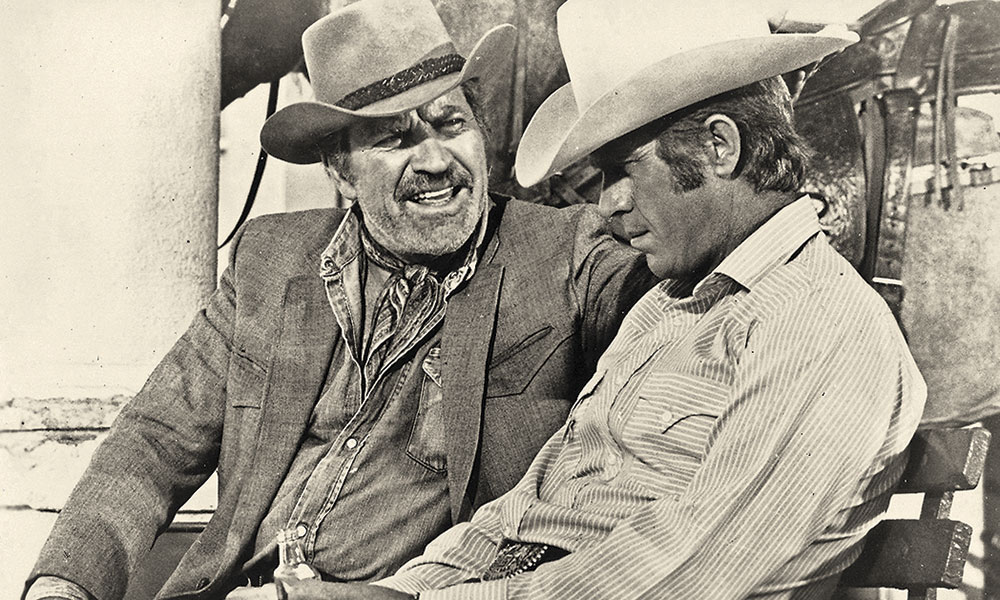

The Santa Fe, Phoenix and Prescott Railway began operating between Ash Fork and Prescott in 1893. When my father first came to Arizona with his mother Jean in February 1945 they arrived on the Super Chief and were met in Ash Fork by Charles H. Orme Sr. The scene at Prescott’s train station, between father and son, Ace and Junior, Robert Preston and Steve McQueen, is considered one of the finest moments—and most personal—for all involved.

Somehow that scene arrived in my mind: the Prescott train depot. I knew Prescott’s Santa Fe, Prescott & Phoenix Railway depot from my many years attending Orme School in the late 1940s. I would be driven to Prescott to board the Santa Fe Railway’s “Peavine” passenger train service that operated from Phoenix’s Union Station to Ash Fork, where I would connect with the cross-country Santa Fe passenger train back home to New York or Virginia, depending on whether it was winter or summer. The depot scene will take place after the annual rodeo parade in which Junior and Ace have ridden and participated. Being turned down by Curly, Ace, thinking that Junior is far more successful in rodeo these days than he is, seeks him out to partner with him and bankroll his dream of Australia. The result: Ace learns that Junior is broke. No way can Junior pay his dad’s way to the Down Under country. Not even a down payment: “Broke, flatter than a tire,” Junior says.

Dramatically and emotionally, Junior and Ace prepare for the third act.

Yavapai County

Most of my father’s school years from 1945 to 1953 were at the Orme School on the Quarter Circle V Bar Ranch, set along Ash Creek in the rolling grasslands and high mesa country 35 miles east of Prescott. His daily life was equally divided between school, sports and ranch chores. Nature and the high desert were ever present in his life and going to town meant 90 miles of dirt road to Phoenix, Saturday night dances in Mayer and Humboldt and town trips in the back of stake bed trucks to Prescott. In Junior Bonner, the film takes McQueen’s character all over the county from Mayer to Prescott and Prescott to Jerome on Highways 69, 89 and 89A, highways that always led my father—and his character Junior—home.

The final day of filming arrived. August 17, 1971. The day was overcast, humid with an ominous thunderstorm forming over the seven thousand feet of Mingus Mountain to the east. This was to be part of the opening of the film with Junior driving into Prescott, and the impending thunderstorm making its presence felt. We were to drive on Highway 89A eastward toward the once-populated copper mining town of Jerome, now a semi-tourist ghost town curiosity, literally perched on the side of Mingus, with the reputation of sliding so many inches a year. Historically, according to Arizona Place Names, copper was discovered there by the Spanish as early as 1582. At the height of its copper mining boom, Jerome had been home to a population of 15,000. …

We filmed. Thunder and lightning and rain arrived. Steve raised the top of the old Cadillac convertible. This will become a part of the opening credits. …

The sun came out. The entire crew ended up in a Jerome saloon. I stood beside Steve at the bar. Like many movie stars, he had no cash on him, despite those six-figure checks Bill Pierce told me about, and he needed a beer. I paid. Small talk. We drank together. …

Tomorrow we were all leaving Prescott.

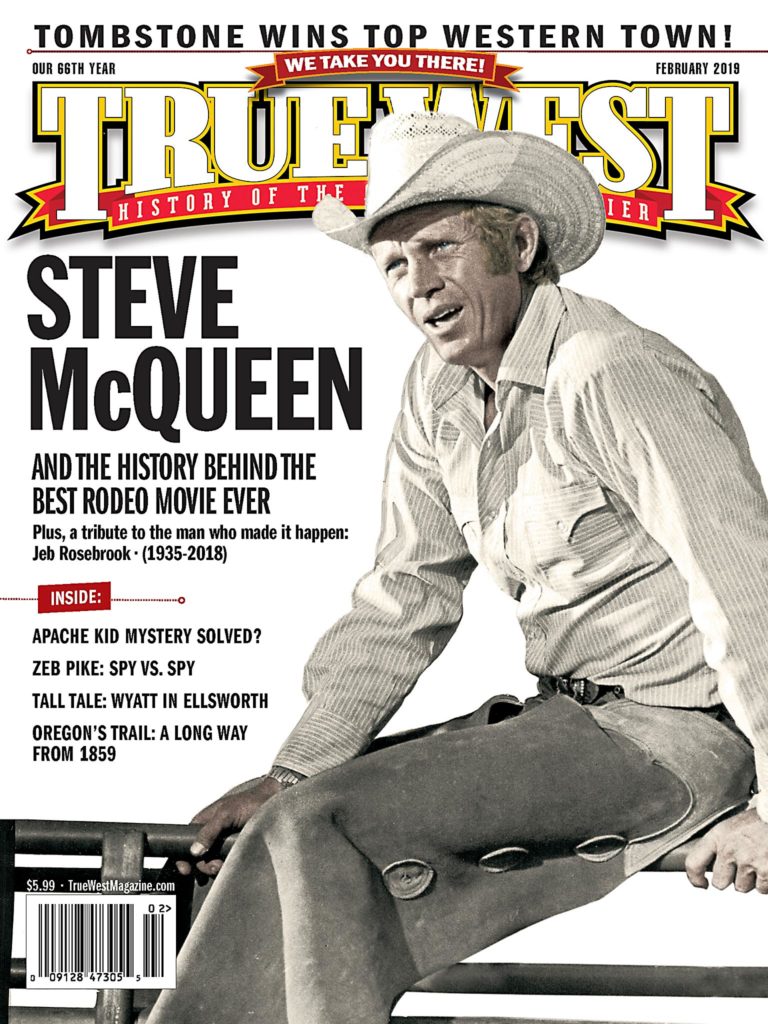

Steve McQueen: The King of Western Cool

When Steve McQueen signed on to star in Junior Bonner in 1971, he was the highest-paid movie star in the world—a position he rocketed to in a very short time considering the competition and era of filmmaking.

McQueen’s first role in a Western was as supporting actor in Goodyear Playhouse’s 1955 episode “The Chivington Raid”, but it was not until a lucky break as a guest star on an episode of Robert Culp’s CBS series Trackdown in the spring of 1958 that his career took off. Soon, McQueen was starring himself on CBS as Josh Randall—in the spin-off series Wanted: Dead or Alive—and his career as the king of Western cool was launched.

When McQueen died prematurely at the age of 50 in 1980, the star of Junior Bonner (ABC, 1972) left a limited, but succinct legacy of classic and modern Western films and television that defined and redefined the genre in McQueen’s inimitable style of cool.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Author’s Note: Jeb Rosebrook and True West’s senior editor Stuart Rosebrook, father and son, first started writing together in the late 1980s when Stuart worked for his father’s production company, Falrose, and his partner, Joe Byrne. They were still writing together until his dad’s passing last year.