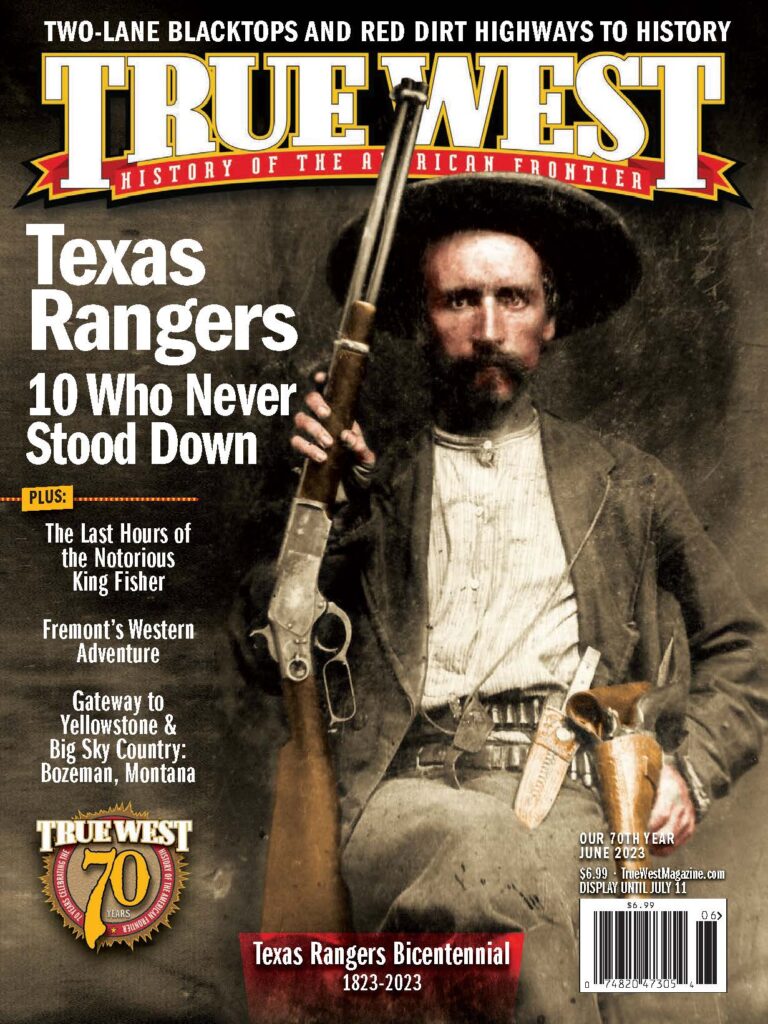

Ten Texas Rangers who never stood down

Now riding into their third century, one of the nation’s oldest law enforcement agencies carries a double-barreled brand known worldwide—Texas Rangers.

In August 1823, in a settler’s cabin on the Colorado River in present Fayette County, Texas, colonizer Stephen F. Austin proposed formation of a 10-man force to serve as “rangers for the common defense.” A dozen years passed before the Rangers first became an arm of the Texas government.

For years, men who rode to safeguard the frontier were not always called Rangers. Early descriptors ranged from “mounted gunmen” to “spies” to “minutemen.” Nor have the Rangers always been about law and order. For their first half century-plus, they saddled up to protect Texas from hostile Indians, not track outlaws. One absolute is that over their two centuries of history they have been both revered and reviled.

But the Rangers were well regarded by most 19th-century Texans—except American Indians fighting to retain their land, outlaws and penurious state lawmakers. The (Marshall) Texas Republican editor wrote in 1855:

“In Texas the name…‘Ranger’ is a household word…associated with noble deeds. He is the defender of the frontier; the protector of the defenseless; the avenger of…wrongs. He endures privations and hardships; sleeps it may be in the wilderness…knows not what moment a lurking savage may shoot him from his horse and scalp him; yet…he is as well contented as if he had all the luxuries of life around him.”

That journalist referred to Rangers in the singular, but while they often worked alone, then as now Rangers operated in organized companies. Still, the attitude and actions of fewer than a score men molded the Rangers’ reputation early on. They were men who would not stand down.

While Austin generally is credited with conceptualizing the Rangers, a young, slight man from Tennessee who came to Texas in 1838 as a surveyor soon fathered their reputation.

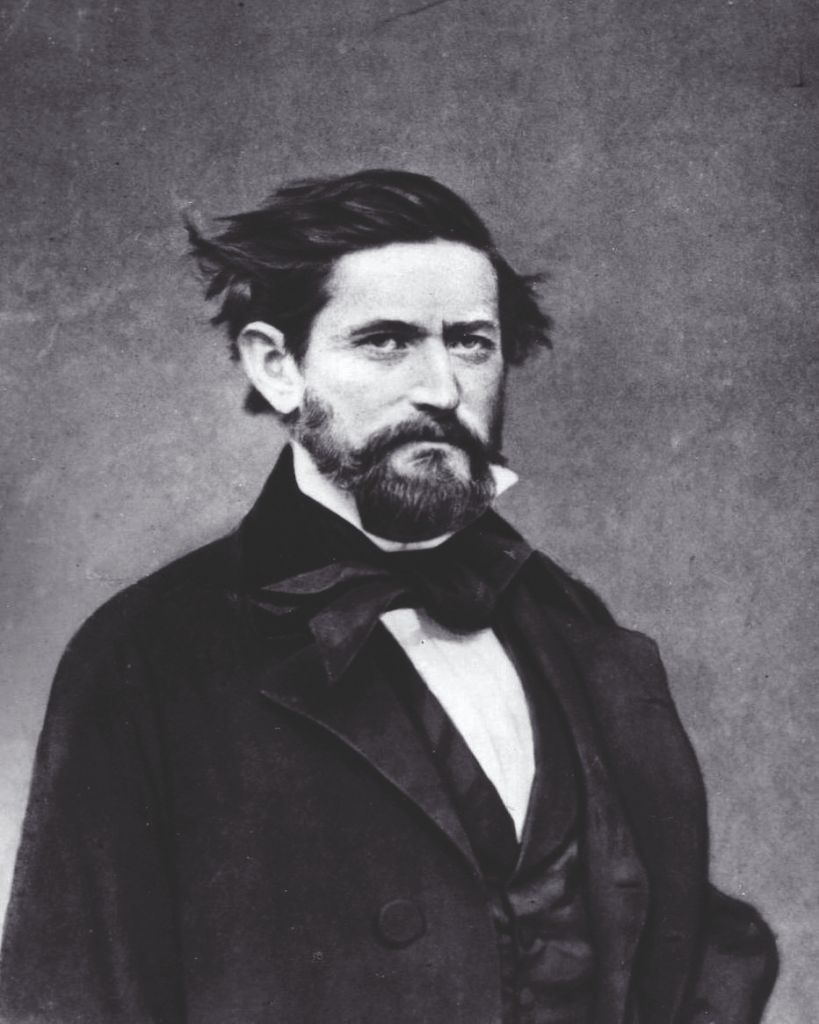

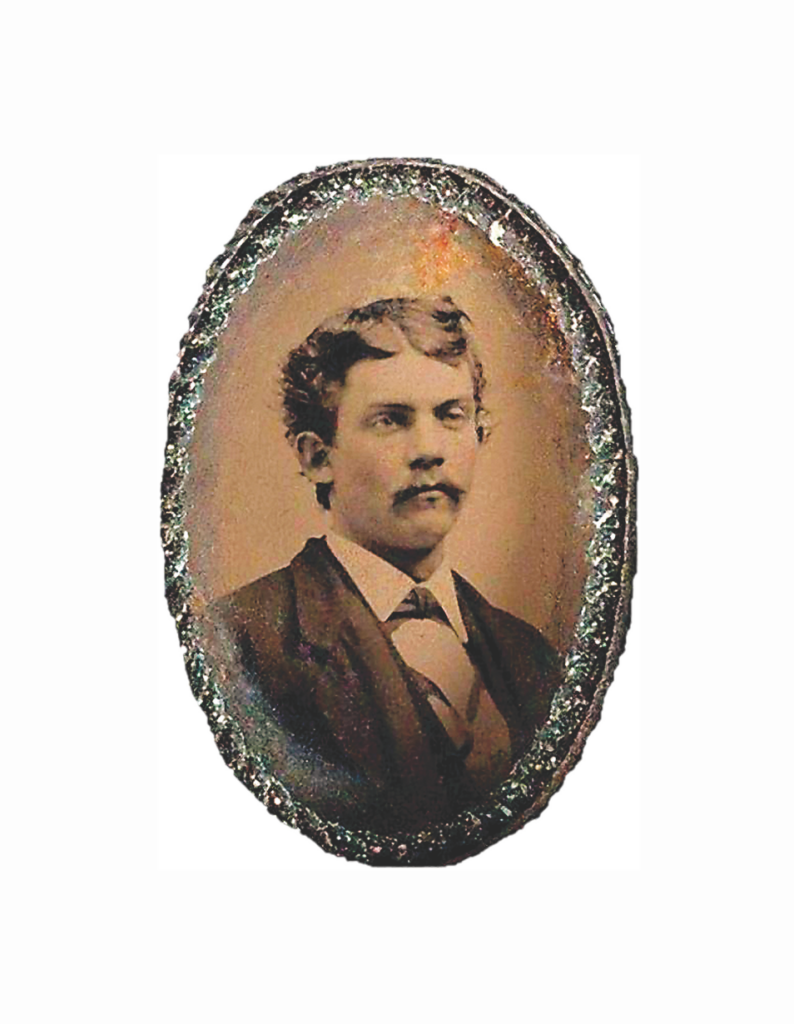

John C. “Jack” Hays

As a surveyor, John C. “Jack” Hays had several close calls with hostile Indians. He soon mixed his work with service as a volunteer Ranger, but it was not until January 1841 that the new Republic of Texas appointed him as a Ranger captain.

On June 8, 1844, near Walker’s Creek in Central Texas, Hays and his smaller Ranger contingent tangled with 70 to 80 Comanches and allies.

“After ascertaining that they could not decoy or lead me astray,” Hays later wrote, “they came out boldly, formed themselves, and dared us to fight. I then ordered a charge; and, after discharging our rifles, closed in with them, hand to hand, with my five-shooting pistols, which did good execution. Had it not been for them, I doubt what the consequences would have been.”

The Rangers killed 23 warriors, badly wounding another 30. Hays lost one Ranger with three wounded.

This battle changed the history of the American West. For the first time, Rangers had fought Indians with an effective close-range weapon that didn’t need reloading after each shot.

Hays didn’t do his work single-handedly, but he proved a leader of men, a savvy tactician, and a fierce fighter.

After further adding to his legend during the Mexican War, Hays left Texas for the West Coast during the 1849 California gold rush. There, he served as sheriff of San Francisco. Later he became a successful businessman. He died in 1883 and is buried in his adopted state.

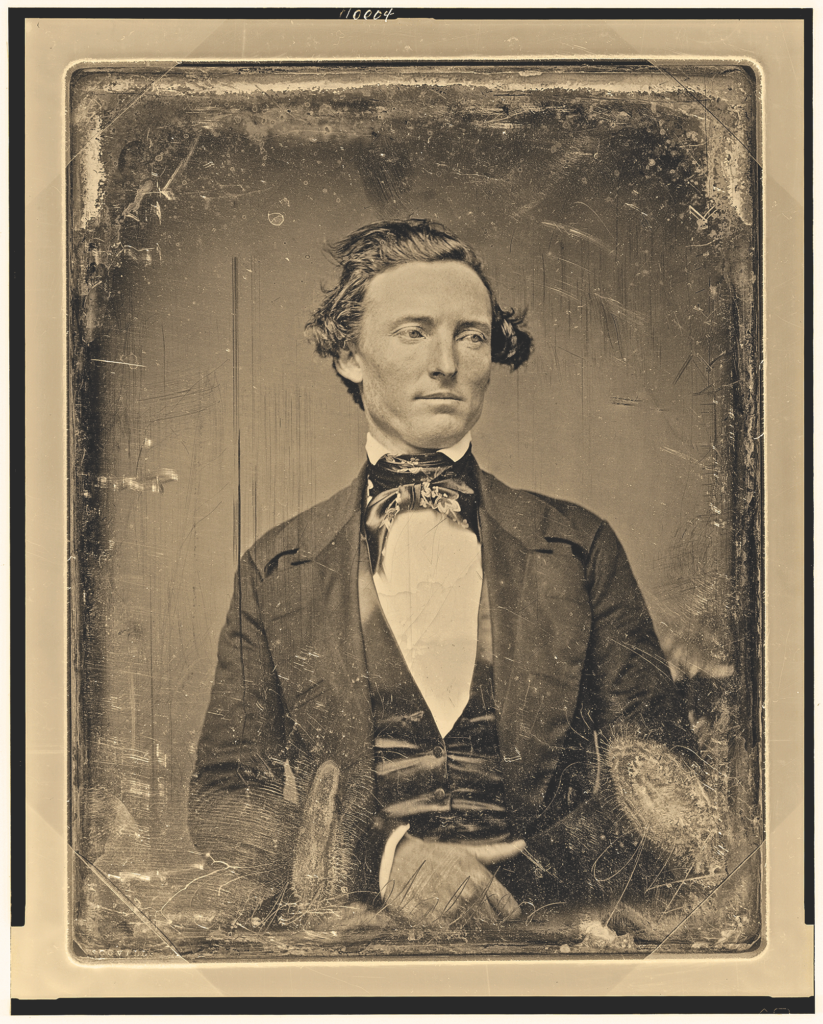

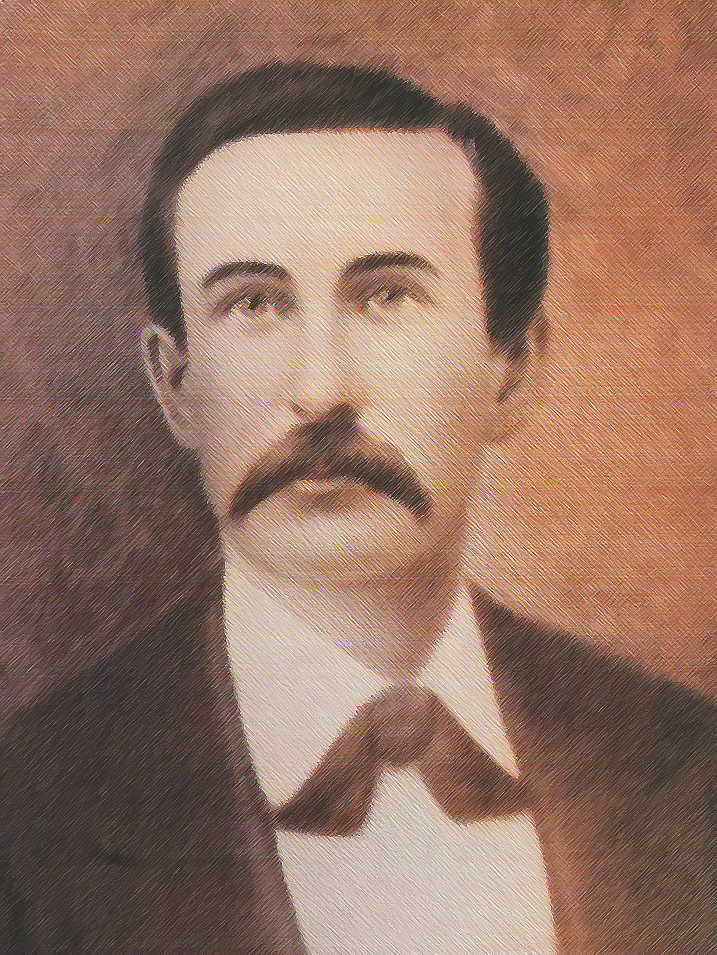

Samuel H. Walker

Samuel H. Walker, born in Maryland, served with the U.S. Army during Florida’s Seminole War. After going to Texas in January 1842, he joined a volunteer company that September and fought an invading Mexican military force bent on reclaiming Texas. That December, captured with other Texans during an attack on the Mexican town of Mier, he was imprisoned in Mexico’s infamous Perote Castle. He escaped in 1843 and early the following year joined Hays’ Ranger company.

That summer of 1844, Walker participated in the Walker’s Creek battle. Though clearly disadvantaged by the Rangers’ new revolvers, the Comanches still proved quite competent with arrow and lance. “In this encounter,” Graham’s Magazine reported, “Walker was wounded by a lance, and left by his adversary pinned to the ground. After remaining in this position for a long time, he was rescued by his companions when the fight was over.”

His fellow Rangers took Walker to San Antonio, where he recovered. Despite his close call, Walker stayed with Hays until the company ran out of funding. In 1845, he served in another Ranger company, this one led by “Ad” Gillespie.

With war with Mexico looming, in May 1846, the battle-hardened Walker formed a Ranger company and scouted for Gen. Zachary Taylor. Once Taylor invaded Mexico, Walker joined a Ranger regiment headed by Hays. Later accepting a captaincy in the regular Army, in October 1846 Walker traveled to the northeast to procure weapons and recruit men for his new unit, the First Regiment, Texas Mounted Rifles.

When Samuel Colt learned Walker was in New York, he wrote to invite him to his shop in Patterson, New Jersey: “I have [heard] so much of [Col. Hays] & your [exploits] with the Arms of my invention that I have long desired to know you personally & get from you a true narrative of the [various] instances where my arms have proved of more than ordinary utility.”

Soon meeting over brandy, Walker gave Colt feedback on his invention. That led to a new, heavier, larger-caliber revolver that fired six shots instead of five. With those changes and a few other improvements, the firearm was called the Walker Colt.

Before Walker returned to Mexico in the spring of 1847, the Army contracted with Colt for 1,000 of the new weapons. Colt, who had no plant of his own, subcontracted with Eli Whitney to manufacture the revolvers.

In appreciation of his input, Colt shipped Walker two of the new six-guns in early October. But Walker did not carry them long. In a battle on October 9, 1847, a Mexican rifleman dropped Walker with a single shot.

When Walker was later reburied in San Antonio, his eulogist James C. Wilson compared Walker to Ad Gillespie, the late captain’s close friend and fellow Ranger: “Gillespie was brave. Walker had no sense of fear. Gillespie did not shun danger.… Walker seemed to seek danger…”

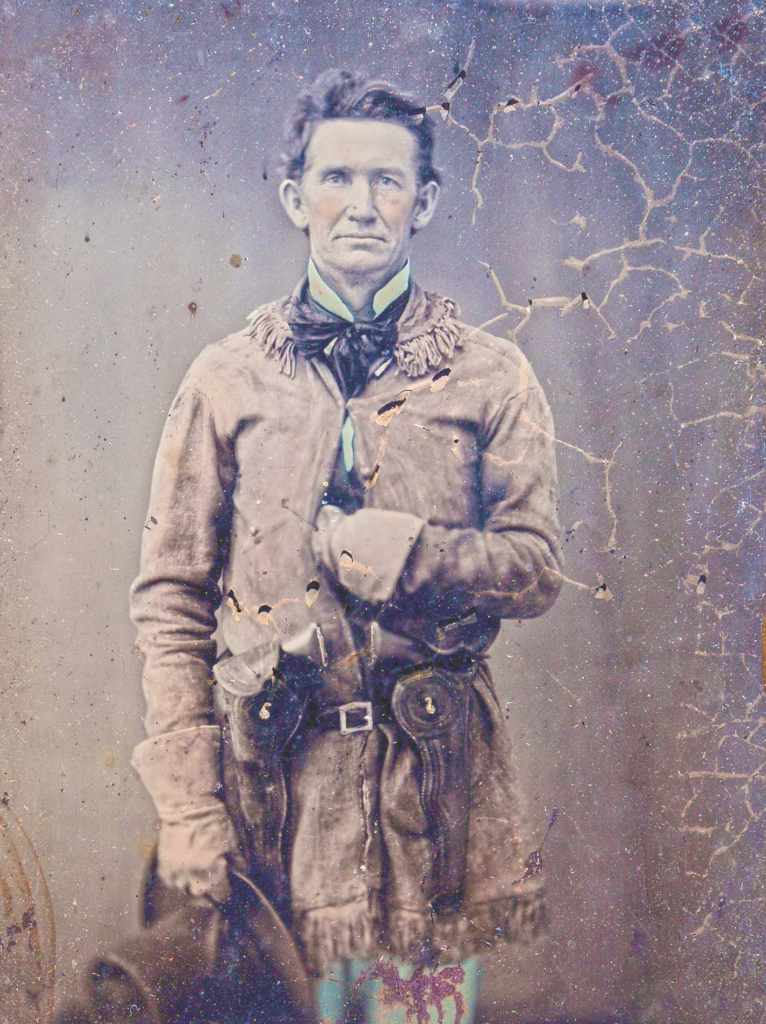

John S. “Rip” Ford

Thanks to newspaper coverage of their exploits before and during the Mexican War, Hays and Walker forged the world’s perception of the Rangers in the 1840s. In the following decade, John S. “Rip” Ford—doctor, lawyer, surveyor, newspaper publisher and legislator—furthered the Ranger image.

Born in South Carolina and raised in Tennessee, Ford came to Texas in 1836. While Texas had already won its independence from Mexico, Ford served in a couple of volunteer Ranger-like companies before turning to his medical and legal practices. He also held a seat in the Republic of Texas Congress and later published a newspaper in Austin.

In the Mexican War, he served under Hays as regimental adjutant. One of his duties involved keeping track of Ranger casualties. On each fatality report, he wrote “Rest in Peace.” Later shortening that to “R.I.P.,” he earned his nickname.

After the war, Ford served as a Ranger captain from 1849 to 1851 and saw numerous Indian fights. He then returned to professional pursuits, but in 1858, when legislators authorized a Ranger force of 150 men, Ford was commissioned as senior Ranger captain.

That spring, Ford and his men splashed across the Red River in pursuit of Comanches who had been raiding in Texas. Less than two weeks later, the captain and his Rangers attacked a Comanche village in the decisive Battle of Antelope Hills.

Beyond his service in the saddle, near the end of his long life, Ford organized an association of former Rangers. Now called the Former Texas Ranger Association, it remains active today. Also, his posthumously published memoir preserved much of early Ranger history. He died in 1897.

Leander McNelly

Never technically a Ranger, battle-tested Civil War veteran Leander McNelly built on Hays’s and Ford’s exploits. In 1870 he became a captain in the newly created State Police, serving in that unpopular uniformed body until its disbandment in 1873. The following year, due to out-of-control outlawry and feuding in South Texas, he was named captain of the Washington County Volunteers. The outfit soon became known as the Special Force, but McNelly and his men were Rangers in function if not name.

McNelly dealt harshly with outlaws and Mexican bandits, even illegally crossing the Rio Grande to recover stolen stock. But McNelly had “galloping consumption” (tuberculosis) and began spending most of his time in San Antonio. The Adjutant General’s office did not like McNeely’s paltry paperwork and began to chaff at the cost of his medical expenses, which the state paid.

And McNelly seemed almost as put out with the powers that be as they were of him. In an interview with the San Antonio Herald in November 1876, the captain complained about “the utter inadequacies of the force at his disposal to the task before him.”

While he commanded 50 picked men, he said it would take four times that many Rangers to rid South Texas of its “vermin.” With 200 men, he said, he could get the job done.

But McNelly got neither the additional men nor much more time in the Rangers. In early February 1877, the state mustered out McNelly and his command but almost immediately created a 24-man company to replace it. On September 3 that year, he died at age 33.

Jesse Lee Hall

Red-headed Lt. Jesse Lee Hall, who had joined McNelly’s command already having a noted reputation as a lawman, became captain following McNelly’s death.

“Capt. Hall is energetic and persevering in his efforts to capture the murderers and rogues in Texas or cause them to fly to a country of safety,” the Daily Fort Worth Standard pronounced on August 23, 1877.

Rangers did not wear uniforms, but Hall set standards. In the summer of 1879, the San Antonio Herald reported that Hall “forbid the wearing of sombreros, fancy top boots, and carrying of white-handled revolvers in his command.” Why? “All these things are characteristic of the desperado, and he wishes his boys to look like civilized people.”

Presumably using wooden-handled six-shooters, that Hall and his men demonstrated their stand-up nature in Atascosa County. Hoping to thwart a planned robbery, the captain and his men staked out a rural store about 20 miles north of Pleasanton. Eventually, five mounted men approached. Two captured the store clerk and three began looting the store.

“Hall then appeared from his concealment and ordered them to surrender, and was answered by a shot,” the November 11, 1879, (Marshall Texas) Tri-Weekly Herald reported. The Rangers returned fire. When the shooting stopped, one badman lay dead with two others wounded. The remaining two bandits escaped.

After numerous other successful operations involving Hall’s Rangers, including Lt. John B. Armstrong’s sensational capture of killer John Wesley Hardin in Florida, Hall resigned in 1880 to pursue business interests. He died in 1911.

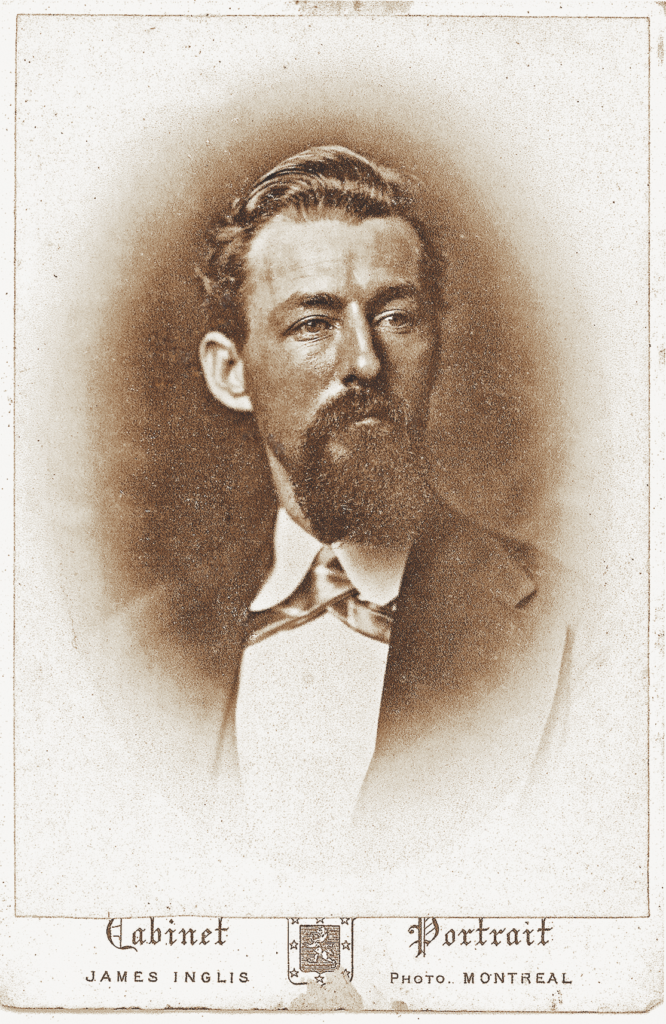

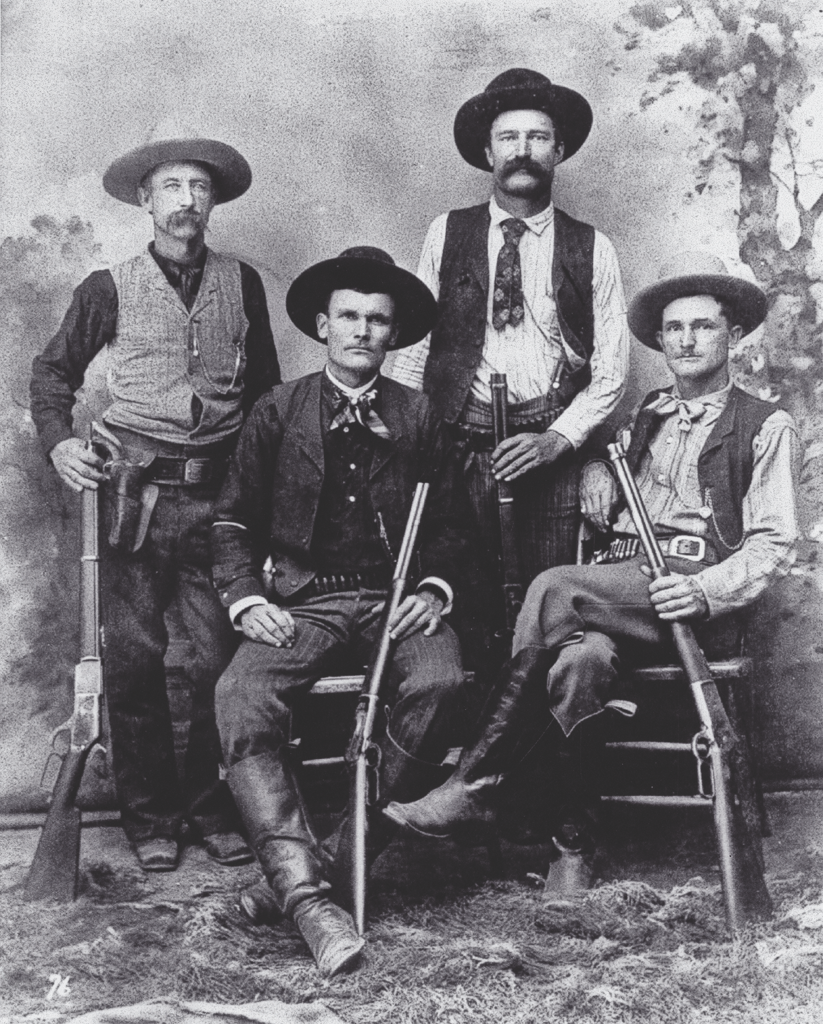

John B. Jones

Courtesy the Author

If Hays and his men spurred on the Ranger legend, John B. Jones hog-tied the Rangers’ reputation as an efficient law enforcement body.

In 1874, legislators created the Frontier Battalion, a force charged with frontier protection. The measure also vested Rangers with law enforcement authority for the first time. The battalion would be under state Adjutant General William Steele with Jones as major in command. Both men had served together during the Civil War.

The Houston Telegram, in December 1877 described Jones as “…the peer of Walker, Hayes [sic], [Ben] McCulloch, and the men whose names are in history and whose exploits have illustrated the romance and daring of life on the Texas border.”

The unknown journalist continued:

“By birth and education a gentleman…this daring chief…is a small man scarcely of medium height and stature, whose conventional dress of black broadcloth, spotless linen, and dainty boot on a small foot, would not distinguish him from any other citizen.”

The newspaper writer went on to say that “it would require a good deal of penetration to see in this quiet, affable gentleman the leader of the celebrated Texas Rangers and the hero of many a daring assault and wild melee, and the bulwark of the border and the terror of frontier forayers.”

Despite Jones’ leadership, the Frontier Battalion was always short-staffed and hamstrung with smaller-than-needed appropriations. But despite the problems they faced, the Rangers stayed in the stirrups and continued to build their renown.

Having survived a bloody encounter with hostile Indians in North Texas in 1875 and the 1878 shootout with Sam Bass’s train-robbing gang in Round Rock, Texas, Jones died at 47 in 1881 of complications following surgery.

John R. Hughes

John R. Hughes first exhibited moxie as a teenager. Born in Illinois and raised in Kansas, at 15 Hughes hired on with a cattle outfit in Indian Territory. When a would-be rustler tried to cull some stock from Hughes’ herd, the youngster took his first stand. It ended with a funeral for the cow thief and a bullet in Hughes’ right arm. After that, he never had full use of the limb, but before long he could draw as fast with his left hand as he originally could with his right.

Hughes continued cowboying until 1878, when with the trail-driving earnings he’d saved he and his brother bought a ranch in Central Texas.

Now 30, Hughes preferred poetry and reading his Bible to any of the easily available vices on the frontier. His pistol stayed in its holster, hanging on the ranch house wall. Unlike many men of his time, Hughes viewed the weapon as a tool for use when needed, not an item of ornamental apparel.

As a rancher, Hughes specialized in horses, building his remuda from herds of wild mustangs still roaming to the west. He was a contented man until one morning in 1886 when he discovered that outlaws had ridden off with 16 of his best animals, including his favorite stallion. Another 54 horses had vanished from neighboring ranches.

“I followed them to New Mexico, got all my horses back and a lot of my neighbors’ horses,” Hughes later modestly related. “Two of [the horse thieves] were…sent to the New Mexico penitentiary.” Hughes forgot to mention that he’d killed three of the horse thieves, leaving only two survivors to stand trial.

Meanwhile, a friend of the thieves came to Texas to settle accounts. But when the would-be assassin arrived at Hughes’ ranch, he happened not to be there. Hughes did not know someone was gunning for him, nor that a Texas Ranger already was on the outlaw’s trail with a murder warrant stemming from a robbery-homicide in Fredericksburg, Texas. Ranger Ira Aten located the gunman before the outlaw could get to Hughes.

“They exchanged shots,” Hughes recalled. “The Ranger shot the pistol out of his hand, but the man got away.… The Ranger asked me to help catch the man.”

Three weeks later, Hughes and Aten found the outlaw. “Unfortunately,” Hughes later put it, “he would not surrender and was killed. His friends then were so annoying to me that I could not go without arms, so the Ranger persuaded me to enlist in the company with him.”

In August 1887, in Georgetown, Texas, Hughes began a Ranger career he expected to last only a few months. But months turned into years. By spring 1890 he’d been promoted to sergeant. Three years later, when Capt. Frank Jones died in a gunbattle with Mexican bandits near El Paso, Hughes rose to captain.

When he retired in 1915, Hughes humbly summarized his Ranger career: “Unfortunately, I have been in several engagements where desperate criminals were killed. I have never lost a battle that I was in personally, and never let a prisoner escape.”

Hughes was 92 before a bullet finally ended his long and rich life. On June 3, 1947, the old Ranger’s body, his .45 nearby, was found in a garage behind a relative’s home in Austin. The captain’s health had been failing, and he did not want to burden his family.

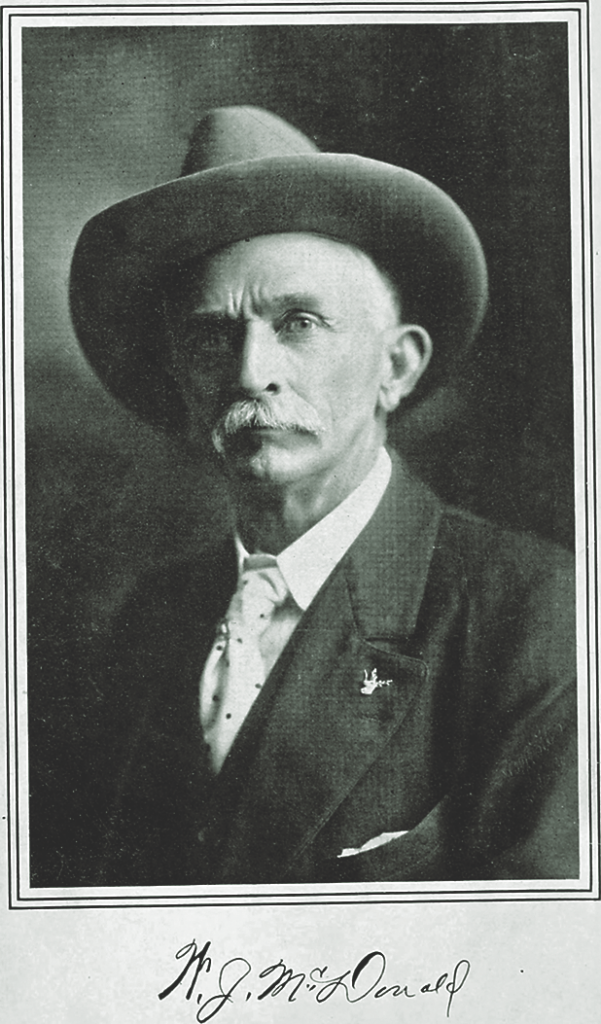

William J. McDonald

With a background in business, ranching and county law enforcement, William J. McDonald was commissioned a Ranger captain in 1890. He’s the Ranger generally credited with first uttering a line that morphed into the slogan “One Ranger, one riot,” but it’s never been definitely established that any Ranger ever said that.

McDonald was both big-headed and bull-headed, but he had sand. He usually got his man and was a pioneer in using forensics—crude as scientific evidence analysis was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

As much as he welcomed publicity, McDonald knew when to keep his mouth shut. “The captain is known to the newspapermen as ‘the squirrel hunter,’” the Austin Statesman noted on June 1, 1903. “It matters not what is happening throughout the state, the newspapermen can only find out from this veteran that he is going squirrel hunting.”

His gutsiest moment came in 1906, when a Black soldier stationed at Fort Brown in Brownsville was accused of attempting to rape a White woman. McDonald and two of his men took the train to the Valley with the captain determined to arrest the trooper. The captain also got arrest warrants for another 11 soldiers suspected of taking part in a riot that had erupted later on the night of the alleged sexual assault. The military would not release the men, and a battle of words ensued that came close to being a real battle between the Rangers and the Army.

The captain did not prevail, and it’s generally accepted that he was overreaching his authority. Still, the so-called Brownsville affair led one Army officer to opine that McDonald would “charge hell with a bucket of water.”

No matter McDonald’s reputation for fearlessness, the captain never killed anyone. He did once get into a bad shooting scape in the Valley, but either his rifle jammed, or he wasn’t able to get off a shot. The Rangers with him, however, did kill several of the parties who’d been firing on them.

McDonald left the Rangers in 1907 for another state job and died in 1918. State lawmakers had done away with the Frontier Battalion in 1901, but the Ranger service continued under a new law.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the old West was mostly a memory. But in the less-settled regions of Texas, the transition from wild and woolly to stable society, took an extra 20 years. For one thing, the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910 and continued for a decade, occasionally spilled across the Rio Grande into Texas. Then, with prohibition came bootlegging. Finally, Rangers had to contend with wide-open oil boomtowns.

The Rangers continued to build on their image, and 166 of them still serve Texas today.

Two Top Rangers of the Early 20th Century

Captain W. L. Wright

Joining the Rangers on the cusp of the 20th century, William L. Wright quickly established his stand-your-ground character. He proved that on Oct. 25, 1900, when a known killer took a shot at him. The gunman missed; Wright did not. Leaving the Rangers in 1902, he served 15 years as sheriff of his native Wilson County. In 1917, he received a gubernatorial appointment as Ranger captain. Not counting two politically related interruptions, Wright served until 1939. He died at age 74 in 1942.

Captain Frank Hamer

One younger Ranger who Will Wright rubbed shoulders with was another Wilson County boy—Francis Augustus Hamer. While he had his critics, most considered him the epitome of the Texas Ranger. Joining in 1906, with some interruptions, he served until 1932. Though best known for his 1934 takeout of the outlaws Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, Hamer’s entire career was a series of events in which he never stood down. He died at 71 in 1955, just after telling his son he’d killed 52 men, all justifiable.