— Benjamin A. Gifford, Courtesy Library of Congress —

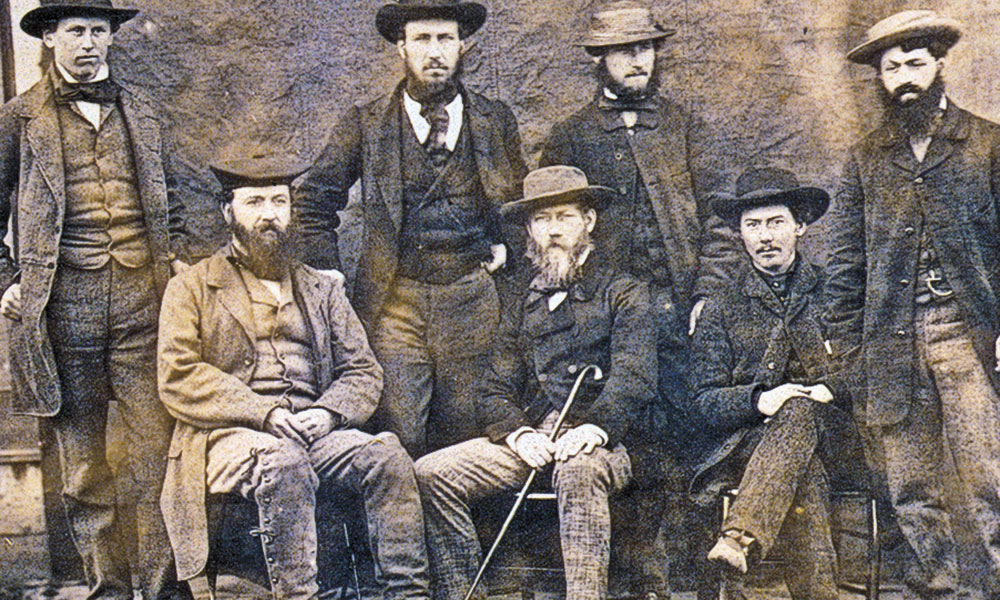

When wealthy trapper Ewing Young died in 1841 in what is Oregon today, he had no apparent heirs, and there was no way to determine how to handle his estate. A meeting after his funeral resulted in a proposal to establish a probate government. The following year, in Champoeg, two meetings to discuss wolves and other animals further galvanized citizens, and in 1843 an all-citizen meeting resulted in the establishment of a provisional government—the first acting public government in the large landmass known as Oregon Country. George Abernethy became the provisional government’s first governor.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

On August 13, 1848, Oregon Territory was officially organized. The 1850 Donation Land Claim Act led to further settlement but forced tribal members onto reservations in many areas of the region. While encouraging settlement, the new leaders nevertheless in 1844 prohibited blacks from entering the territory by passing the Black Exclusion Law that also prohibited slavery. Those black citizens who were already in the territory were forced to leave or they were beaten. Owners of slaves were required to free them. While most black residents left the territory, some remained, usually in hiding. With the population continuing to expand due to immigration, Oregon was denied statehood several times as Congress argued whether the territory should be admitted as a “slave” state or a “free” state.

After years of debate, Oregon was admitted to the union on February 14, 1859, and holding with the early stance of opposing black residents, the state constitution had a “whites only” clause. But there had not always been exclusion for blacks in the region. The first black man to vote in the area did so on November 24, 1805, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition made a decision about where to spend the winter. In that vote among expedition members, Captains Lewis and Clark included Clark’s black slave, York, and the Shoshone woman Sacajawea, who voted “in favour of a place where there is plenty of Potas.”

— Courtesy Travel Oregon/Kenji Sughara —

Experience Oregon

The challenges and conflicts of settlement and statehood, as well as the connections to home, land and water are themes explored in Experience Oregon, which opens at the Oregon Historical Society in Portland in time for the 160th anniversary of Oregon Statehood on February 14.

Visitors will experience a covered wagon, like the conveyance that brought thousands of settlers to Oregon in the 19th century. A 180-degree theater presentation will reflect the people, places and issues of Oregon’s past and present.

The new permanent exhibit will offer unprecedented opportunities for visitors from all backgrounds to connect with Oregon’s rich and complex history.

Bounded on its northern border by the Columbia River and to the west by the Pacific Ocean, the state has a strong connection to water. Our journey through Oregon 160 years after statehood begins on the Oregon Coast, at Astoria, the Pacific Fur Company post that John Jacob Astor founded as he launched his fur empire. Nearby is the location of Fort Clatsop, now a part of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, the winter camp for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

— Courtesy NPS.gov —

The earliest Europeans to see the Oregon Coast came by ocean centuries ago. David Thompson of the North West Fur Company and John McLoughlin, chief factor of Hudson’s Bay, plus the trappers who came in their wake, followed the Columbia River from its source in Canada to the Oregon coast. With the arrival of Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, traders and trappers—by sea and overland—began the American challenge to claim the territory.

Attempts to ensure American control quickly centered on population, which led to overland migration by families who forged and followed the Oregon Trail beginning in 1841. Those pioneers established homes in the Willamette Valley, settling in Oregon City, Aurora and Champoeg, where the first government organization began, leading to statehood.

The Capital City

The explorations in Oregon extend to Salem, the present state capital, and south to Eugene and Corvallis, where pioneer-era barns and houses are still in use, and on to Bend, home to the High Desert Museum.

The predominant route across Oregon to the Willamette Valley—followed by David Thompson, Lewis and Clark and the Oregon Trail pioneers—traveled along the Columbia River. Some used boats, others wagons, or horses, or their own two feet. One of the longest-used locations beside the river is The Dalles, now the location of the Columbia River Discovery Center, but for centuries served as an important trade and fishing center for American Indians.

— Courtesy BLM.gov —

The Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail travelers stopped at The Dalles. Some converted their covered wagons to watercraft at this location. Others after 1846 turned south into Tygh Valley and then continued overland on the Barlow Road, a toll route through deep forest cutting across the Cascades and around Mount Hood. This road, forged by and named for John Barlow, ended at the Philip Foster Farm in Boring.

The Oregon Trail struck the Columbia River after crossing the Blue Mountains in eastern Oregon. The Tamástslikt Cultural Institution near Pendleton is one of the better sites to visit in Oregon that highlights the Native population. Farther east near Baker City the ruts of the Oregon Trail are clearly seen from atop Flagstaff Hill. Many a pioneer who was headed west to the Willamette Valley likely stood on that hilltop and wondered at the challenges ahead.

— Courtesy The Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site —

Those pioneers were the men and women who forged the state of Oregon, which has evolved from its early attitude that prohibited slaves and free blacks from having a home in the region. Today, Oregon is known for diverse historic sites, an eclectic population and, of special interest to weary travelers, craft breweries. An exhibit at the Oregon Historical Society, “Barley, Barrels, Bottles, & Brew: 200 years of Oregon Beer” will be displayed until early June.

Oregon is known for wide-open spaces, ranch country and cowboy culture at the Pendleton Round-Up, held each September. It’s also the homeland of Chief Joseph

and the Nez Perce, even though they were forced to leave in 1877. Their descendants return annually in the summer for ceremonies and celebration.

Portland has one of the great bookstores of the West—Powell’s Books—and the Gorman House in Corvallis is one of the oldest homes for black residents. It was built for pioneers Hannah and Eliza Gorman, a mother and daughter who

came to Oregon in 1844 as part of John Thorpe’s Oregon Trail Company. They were identified as “Eliza, a mulato girl” and “Aunt Hannah, a negress.”

Indeed, Oregon has come a long way from its territorial and early statehood era of Black Exclusion and “whites only” laws.

Wide Spot in the Road

The Kam Wah Chung State Heritage Site in the town of John Day houses an excellent collection that reflects Chinese immigration in the American West. The 1866-era building may have been a trading post before it was leased to Kam Wah Chung Company and later purchased by Doc Ing Hay, an herbal medicine practitioner, and Lung On, a general store merchant who had immigrated from Guangdong, China. They used it as their home and it became a social center for the local Chinese population.

When Hay died in 1952, he left the building to John Day, intending that it become a museum. It took decades, but the building was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 2005, has been renovated and is now the museum Hay intended. Among the items in the museum’s collections are personal documents and company records from the building’s original owners.

Good Eats & Sleeps

Grub: Portway Tavern, Astoria; Pine Tavern, Bend; 1889 Café in the Geyser Grand Hotel, Baker City; Baldwin Saloon, The Dalles; Huber’s Café, Portland; Hamley’s Steakhouse, Pendleton

Lodging: Timberline Lodge, Mt. Hood; Geyser Grand Hotel, Baker City; Pendleton House, Pendleton; Sentinel Hotel, Portland; Black Butte Ranch, Sisters; Oregon Hotel, McMinnville

RV Parks & Campgrounds: Cannon Beach RV Resort, 340 Elk Creek Rd, Cannon Beach, OR, (503) 436-223 • CBRVResort.com

Pendleton KOA, 1375 SE 3rd St, Pendleton, OR, (541) 276-1041 • PendletonKOA.com

Candy Moulton recommends reading A Light in the Wilderness by Jane Kirkpatrick, for a novelist’s view of the Oregon Black Exclusion Law and how it affected early pioneers.