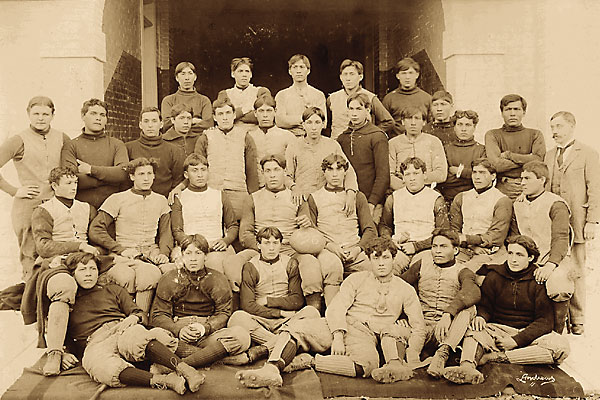

Ben American Horse eyed his white opponents, ranged across the field of battle on a cool day in November 1894.

They were better equipped, more experienced and had every advantage. But Ben had tradition on his side—and a desire to get even with his rivals for the oppression and degradation he and his people had suffered over the years.

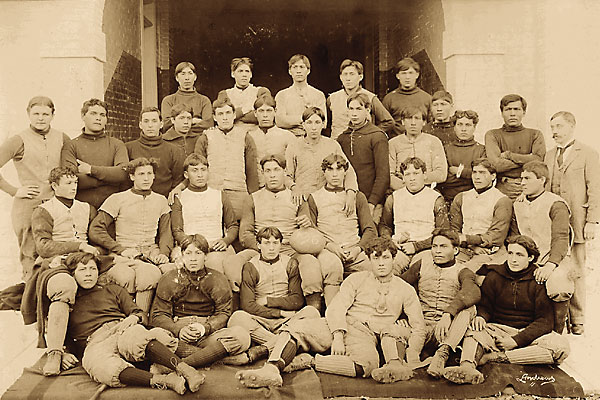

It was payback time for Ben American Horse and his teammates on the Carlisle Indian Industrial School football team.

Their story is told in the new book The Real All Americans by noted sportswriter Sally Jenkins. She remarkably recounts our nation’s attempt to assimilate Indians into white society in the latter part of the 1800s and how the students at the famed Carlisle used a game to regain some of their pride. They did so in ways never seen before.

Carlisle changed football forever. The forward pass, the reverse, the end around, the crouching start and the single wing and double wing offenses? All came from Carlisle. The players were the first to wear shoulder and thigh pads. Another novelty to the game was the number sewn on the back of each young man’s jersey. Yep—a bunch of so-called backward Indians taught the white teams a thing or two about a game first developed by colleges founded during America’s colonial period.

Ben American Horse

Oglala Sioux leader American Horse, who helped defeat the U.S. Army in Red Cloud’s War back in the late 1860s, knew, within a decade, that his children had to learn to live in white society. He sent some of them to Carlisle when it first opened in 1879. When his son Ben reached an appropriate age—probably early teens, although the record is unclear—he, too, went to Pennsylvania in 1889.

Far from home and in a different climate and environment, Ben, like the other students, was not allowed to speak his native language or wear traditional garb. His hair was cut short (a near sacrilege in Indian culture), and he wore a military uniform. The school forced him to convert to Christianity.

Many students were demoralized; some literally died of broken hearts. But they quickly took to the game of football. The physical challenges and competition appealed to their nature. The Indians had been playing for several years at that point—Ben and his pals usually competed against each other in intramural contests. By 1894, school superintendent Richard H. Pratt decided that playing outside opponents would be good for student morale. So he scheduled five games against teams like Bucknell, Lehigh and Navy.

Ben American Horse and his teammates were relatively small, several inches shorter and about 20 pounds lighter than the whites they played. The whites had better equipment and facilities, they were better coached and they had the home field advantage. Yet Ben and his mates were fast, deceptive, smart and motivated—they wanted to stick it to “The Man.”

Ben played end (on offense and defense) but carried the ball frequently, usually taking it several yards behind the line of scrimmage and then leaping over the line for big gains. His teammates called him “Flying Man.”

Their grit wasn’t enough. Carlisle lost all five games in that inaugural year, although most scores were close. The Indians got national publicity and grudging respect from observers and opponents. It clearly was a moral victory. Sort of.

Ben American Horse played just two years before he returned to his tribe at the Pine Ridge Reservation. He worked with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show and served his tribe as a chief and police officer. Ben would recall his days at Carlisle as some of the best of his life.

Within 17 years, Carlisle was among the best football teams in the country—and it featured the legendary Jim Thorpe, probably the best player of his era. In the ultimate replay of the Indian Wars, he and the Indians upset the U.S. Military Academy (with linebacker and future president Dwight Eisenhower) in 1912. The game didn’t change the past, but revenge was sweet.

Indians across the country, including Ben American Horse, shared in the victory.

The Real All Americans by Sally Jenkins is published by Doubleday and available at your local bookstore. Visit randomhouse.com for more information.