During an era of official segregation in the U.S. Army, chaplains ministered to both black and white Union regiments fighting in the Civil War. Nearly two decades passed before the Regular Army followed suit, for motives that were as much practical as they were religious.

During an era of official segregation in the U.S. Army, chaplains ministered to both black and white Union regiments fighting in the Civil War. Nearly two decades passed before the Regular Army followed suit, for motives that were as much practical as they were religious.

Many enlisted men in the post-Civil War Army were illiterate. This particularly proved true for blacks who had been enslaved in the American South, where paranoia and prejudice led to laws that prohibited their formal education. As an early regimental history of the 9th U.S. Cavalry reported, “…the enlisted men were totally uneducated; few indeed could read and scarcely any were able to write even their own names.”

To address this challenge, the 1866 congressional legislation that created four black infantry units and two black cavalry outfits included the hiring of regimental chaplains to provide both religious and educational duties for the enlisted men. The religious tradition of black martial congregation, unfortunately, was ignored, at first, nor did the Army attempt to include black clergymen as chaplains who understood that tradition.

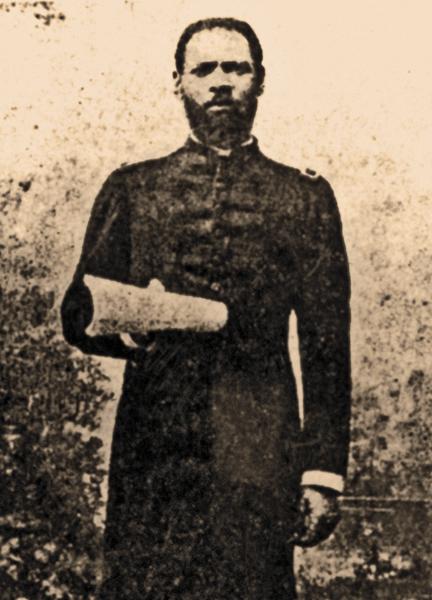

But in 1884, the first step to rectifying that lack occurred with the commissioning of Henry V. Plummer, as chaplain of the 9th U.S. Cavalry. Born on June 30, 1844, Plummer was an enslaved field hand in Prince George’s County, Maryland. His status changed when the Civil War offered a means to break his chains of bondage. Plummer joined the U.S. Navy, serving for about 16 months until his honorable discharge in the summer of 1865. By then, he had learned to read and write.

Plummer continued his education as best he could, when not carrying out his duties as a night watchman in a Washington D.C. post office. He managed to save some of his meager salary from this job and his outside income as a political worker, which enabled him to become a student at Wayland Seminary. Before, during and after his course of study at the seminary, he served as a Baptist pastor or as a missionary in both Maryland and Washington, D.C.

Based upon these varied experiences, Plummer secured letters of recommendation from numerous clergymen. Noted abolitionist author Frederick Douglass supported Plummer’s bid for a chaplaincy in a black regiment. When white Chaplain Charles C. Pierce resigned from the 9th Cavalry, Plummer found his chance. He reported to his first military post, Fort Riley, in Kansas.

Upon his arrival, the July 12, 1884, edition of the local newspaper The Junction City Union noted the clergyman, “well merits the office given to him.”

At Fort Riley, Plummer found ample work. Not only was he the chaplain, but also he served as superintendent of post schools and as manager of the fort’s bakery. His first year in Kansas passed with considerable success in all these areas of responsibility. Plummer drew favorable attention from an Army-Navy Journal correspondent, who had attended one of the chaplain’s services, where he heard, “one of the best sermons and prayers” he could remember from any preacher.

In 1885, Plummer transferred to Fort Robinson in Nebraska, the headquarters of the Department of the Platte, which stretched along the Platte River in Nebraska, Idaho, Utah and Wyoming Territories. This period of his military life allowed him to focus on the educational needs of his soldier-students. He made recommendations for adequate funds to provide supplies and equipment, as well as establish a ”Bureau of Education and Literature,” to create an Army-wide standard for books and furnishings in the post schools and libraries. He also recommended that the military require illiterate enlisted men to attend school during the long winter evenings.

Favorable opinions of the chaplain continued. In May 1892, Fort Robinson commander Lt. Col. George B. Sanford remarked that the uniquely large church attendance at the post could be attributed to the “efficient manner in which the chaplain carries out his work.”

Plummer also crusaded against liquor, but alcohol, unfortunately, contributed to the end of his military service. On June 2, 1894, the chaplain took part in a promotion celebration at the quarters of Sgt. Maj. Jeremiah Jones, where Plummer allegedly drank liquor, used vulgar language and manifested other traits of disgraceful conduct. These complaints came from Saddler Sgt. Robert Benjamin, a soldier whom Plummer had occasionally disciplined for failure to perform duties at Fort Riley’s bakery. Perhaps more damning was the accusation that Plummer had made waves with the post commander at Fort Robinson.

Both that officer, Lt. Col. Reuben F. Bernard, and the regimental commander, Col. James Biddle, came to view the clergyman as a disruptive force. They suspected, but had no evidence, that Plummer had written articles in a Nebraska newspaper about “racial injustices” experienced by black troops and that he was behind the distribution of a circular to the troops speaking out against discrimination in the nearby civilian town of Crawford, in 1893, after black soldier Charles Diggs had escaped a lynch mob in Crawford by fleeing to Fort Robinson. Signed “500 Men With the Bullet or the Torch,” the broadside warned Crawford citizens, “…if you persist we will repeat the horrors of San Domingo—we will reduce your homes and fireside to ashes and send your guilty souls to hell.”

Charging that Plummer was creating a “disturbing element” within the command, Plummer’s superiors accused him of conduct unbecoming an officer. After an 11-day court martial, Plummer was found guilty and dismissed from the service. Plummer responded to his dismissal: “I cannot help to remember…that patriotism and devotion to duty, counts for naught against falsehood and prejudice in the regiment under the present regime.”

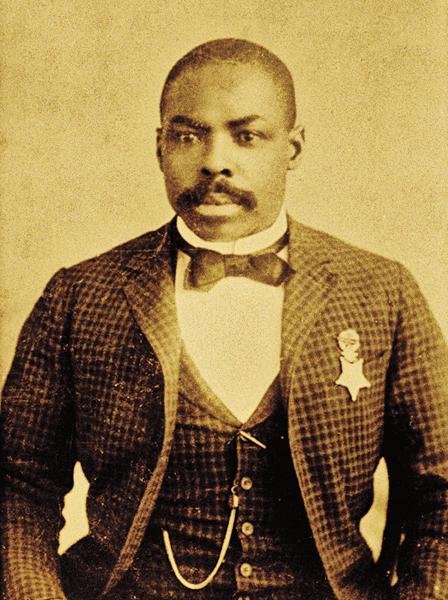

Fortunately, Reverend Plummer’s fate did not end opportunities for black chaplains. During the remaining decades of the late 19th century, four other black chaplains followed in his footsteps: Allen Allensworth, who served from 1886 to 1906; Theophilus G. Steward, who served from 1891 to 1907; George W. Prioleau, who served from 1895 to 1920; and William T. Anderson, who served from 1897 to 1910. Four years after Plummer’s dismissal, a black chaplain made it to the top of the chain—at least, temporarily. When the 10th Cavalry was sent to Cuba in 1898, Anderson was left in charge of Fort Assiniboine in Montana, making him the first black to command a U.S. Army post. When his replacement arrived in June, Chaplain Anderson joined his outfit overseas.

These remarkable Christian soldiers watched over their military flocks. In many ways, their influence as moral models and mentors helped pave the way for renowned spiritual leaders and civil rights champions, such as the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., who followed a trail blazed by these pioneer martial ministers.

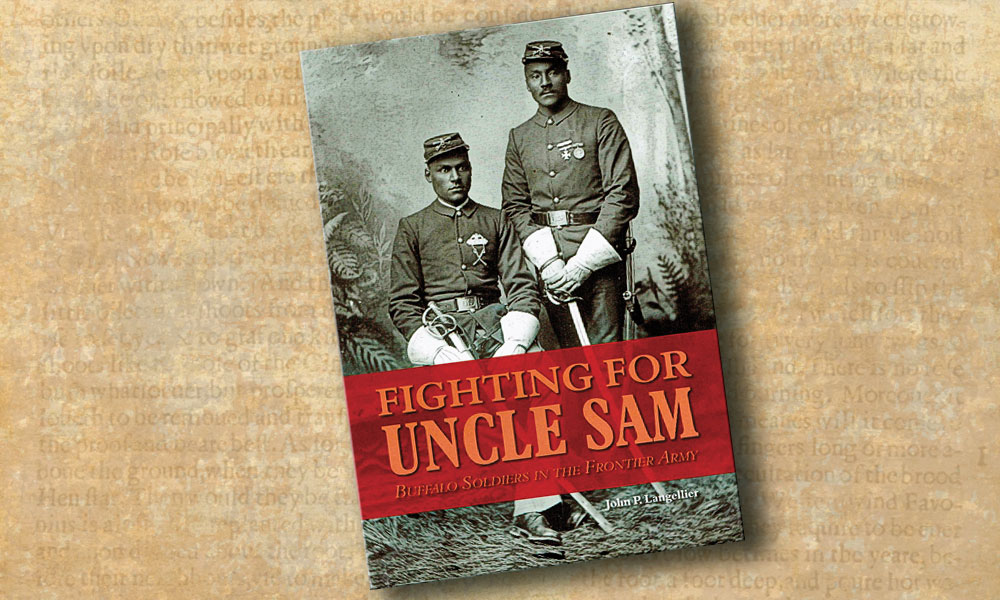

John Langellier received his PhD in military history from Kansas State University. After a 45-year career in public history, he retired in Tucson, Arizona, in 2015. He is the author of dozens of books, including Fighting for Uncle Sam: Blacks in the Frontier Army, due out in early 2016.

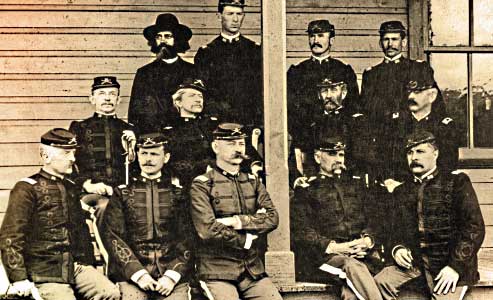

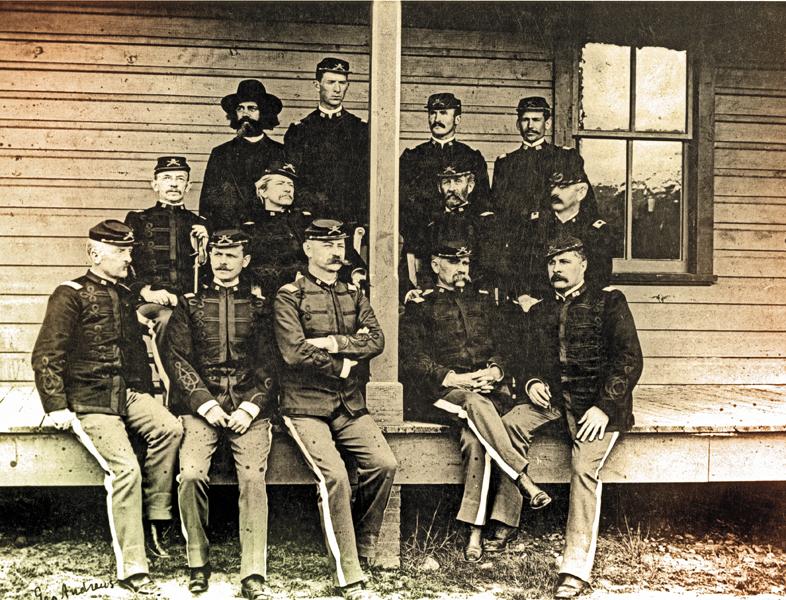

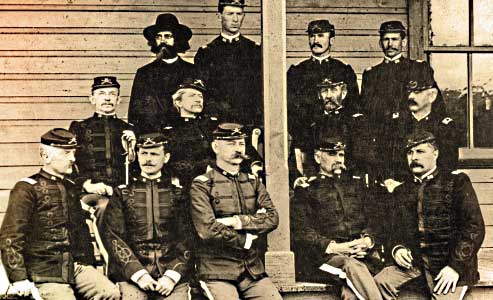

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration –

– Courtesy United States Military Academy Library –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Anthony Powell Collection –

– Courtesy Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University –

– True West Archives –