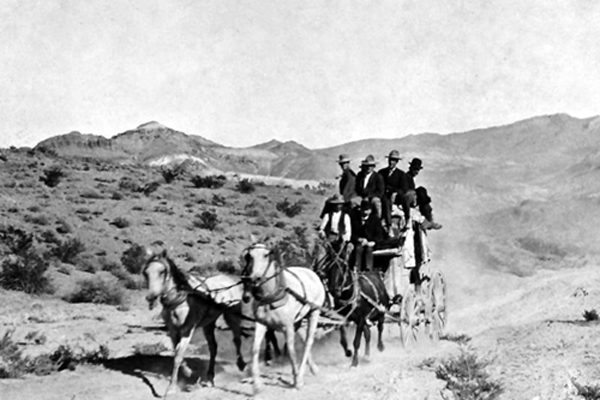

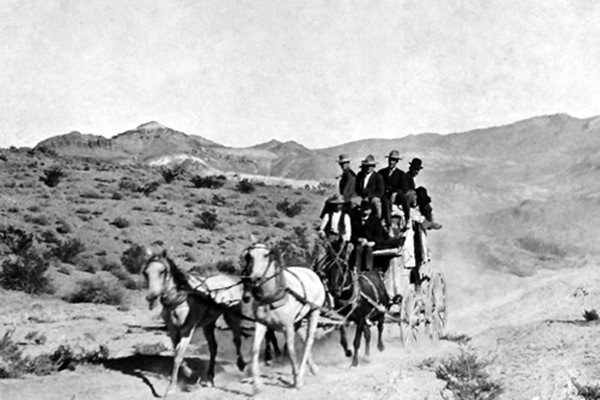

Riding on the Butterfield Overland Mail during the 1850s could be a harrowing experience. Passengers bumped their heads on the roof as the coached bounced along the dusty road. It was sheer novelty at first but as night fell, the hardships of coach travel was brought to all. Some managed to doze but never for long, amidst the rumble of the coach. Sheer exhaustion allowed some to sleep after a couple of nights on the road but others were driven insane by the ordeal. It was reported that during one trip across southern Arizona a passenger suddenly leaped from a moving stage and ran off screaming into the desert never to be seen again.

Riding on the Butterfield Overland Mail during the 1850s could be a harrowing experience. Passengers bumped their heads on the roof as the coached bounced along the dusty road. It was sheer novelty at first but as night fell, the hardships of coach travel was brought to all. Some managed to doze but never for long, amidst the rumble of the coach. Sheer exhaustion allowed some to sleep after a couple of nights on the road but others were driven insane by the ordeal. It was reported that during one trip across southern Arizona a passenger suddenly leaped from a moving stage and ran off screaming into the desert never to be seen again.

One passenger recalled how a runaway team pulled his coach down a steep bank, bouncing the body completely off the running gear. The mules bolted, dragging what was left behind them after a short distance the wheels flew off, and when the mules were caught they were dragging just the axles. One passenger was badly cut and the others stunned but in one hour, after patching the stagecoach together, they hit the trail again.

Another wrote: “Twenty four mortal days and nights–must be spent in that ambulance; passengers becoming crazy with whiskey, mixed with want of sleep, are often obliged to be strapped into their seats; meals dispatched during the ten-minute halts are simply abominable, the heat excessive, the climate malarias; lamps may not be used at night for fear of non-existent Indian raids.”

A surefire way to handle customer’s gripes was developed by one driver: “We had a way of managing them…when they got very obstreperous; all we had to do was yell ‘Indians’ and that quieted them quicker than forty-rod whiskey does to a man.”

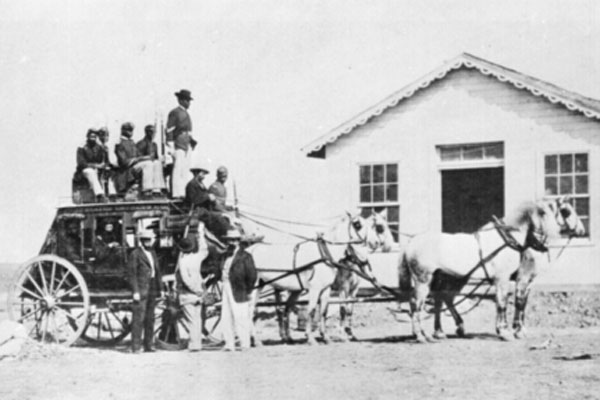

The driver had unlimited authority on the expedition. Women were special and were treated with great respect. The standard punishment for those who took liberties with a female was set afoot, whether in dangerous Indian country or not. It was also considered unwise to discuss politics or religion on board.