The Westerns often had it wrong.

The Westerns often had it wrong.

They made gunfights so neat and clean, even with all the blood and bullet holes.

Most cinematic gunfights went like this: bad guys hurt or kill a friend of the good guy. In a showdown with the bad guys, the good guy wins, gunning most or all of them down. The good guy then rides off into the figurative sunset, with the pretty girl by his side.

Reality was different.

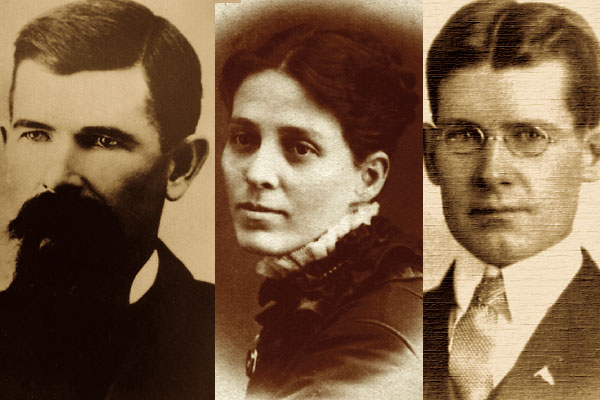

Take the attempted holdup of the Farmers and Merchant Bank in Delta, Colorado, on September 7, 1893. The McCarty Gang botched the job, killing bank teller and co-owner Andrew Trew Blachly.

Although a local sharpshooter did kill two of the bad guys, the good guy—Andrew—left behind a wife named Mary, with a 160-acre farm and eight sons, ranging in age from 1 to 15. He also left a lot of debt. The family was impoverished. The future looked bleak.

In countless similar situations, families were destroyed. Kids were shipped out to relatives or friends, or apprenticed to ranchers or businessmen. Mothers took on menial jobs, just to survive. The terrible circumstances often passed down to several generations.

The Blachlys were different.

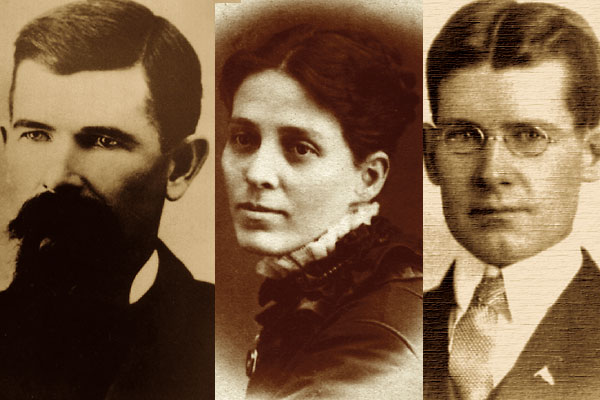

Mother Mary—known to one and all as Dellie—had been born in Siam (now Thailand) to missionary parents. She studied at Oberlin College before marrying her cousin Andrew in 1877. A strong woman, Dellie dealt with her husband’s frequent illnesses, adapted to several moves and handled more than her fair share of days without money. She was a woman with sand, with no quit in her.

Dellie sold the farm and moved the family to a 40-acre spread nearby, setting aside four acres for fruit trees and running cattle on the rest. A 1905 book on prominent citizens of western Colorado called Dellie a “very good manager and a lady of great industry and enterprise.”

Slowly but surely, the Blachlys fulfilled one of Andrew’s dreams: to send all the boys to college. Yet the path to earning those degrees was anything but easy.

Take for example Lou, who was just shy of four when his father was murdered. In 1911, he headed to Ohio to attend his mother’s alma mater, Oberlin. After a year, he quit college to sell “mendless” socks to fund his older brother Fred’s graduate studies at Columbia.

The next year, Lou studied at the University of Wisconsin, receiving financial aid from Fred, now working as a professor at the University of Oklahoma. But when Hal, who ran the family ranch, died in 1915, Lou moved back to Colorado to help his mother.

After another year, Lou returned to his studies in Wisconsin, yet he interrupted his education to fight in WWI in 1917. With the war over, he finally earned his bachelors in economics at Wisconsin in 1919.

The 30-year-old Lou had waited out nine years to get his degree. That’s perseverance.

Lou used that education to his advantage, first working for the federal government and then for the Silver City Enterprise newspaper in New Mexico. He interviewed hundreds of local pioneers, then wrote books on Southwestern animals and plants before dying in Tucson, Arizona, in 1965.

The other Blachly boys enjoyed their own successes. One became a physician. Two were noted economists. Four others were prosperous ranchers.

Dellie lived to see the fruits of her labor before her death in 1926.

The successes of the Blachly family is a heck of a story. Two brothers, Fred and Lou, recorded their family history in separate manuscripts. Both are remarkable documents, painting vivid pictures of a tough life in the late 19th- and early 20th-century West. Family members still treasure these documents, proudly.

Should those accounts ever get published, make sure to get copies. I will. Because the story of the survivors of Andrew Blachly, tragically killed during an Old West stickup, proves one thing for sure: real life often beats the Westerns, hands down.