The year was 1883, and muleskinners were earning more than college graduates ($120 per month).

It was hard-earned money, fraught with danger both natural and man-made. The miracle mineral borax, located in the very center of Death Valley, had been used for centuries to “fire” ceramics and as medicine to cure everything from rheumatism to alleviating palpitations. The only other deposits were found in Italy and Tibet, extremely expensive to import. The Harmony Borax company was willing to pay top dollar to have it hauled from Death Valley located in both Nevada and California. Today, it is a multi-million dollar industry used in hundreds of merchandise including cleaning products, glass, fertilizer, medicines and as an insulator on the space shuttle. Some of you may have first heard of borax on NBC’s Death Valley Days, for which 20 Mule Team Borax served as its primary sponsor.

Muleskinners had to be combination blacksmith, wheelwright, wrangler, veterinarian and frontiersman as Death Valley tested their endurance, stamina and resilience. From Furnace Creek to the railroad at Mojave, California, the mule teams hauled borax past the lowest point in the U.S. at Badwater (282 feet below sea level), across desert, enduring scorching heat, where temperatures reached 130 degrees Fahrenheit and the ground temperature could reach 165 degrees. Add to this the threat of coyotes, rattlesnakes, scorpions and thirst.

The trail tracked along the Funeral Mountains to the east, skirting the Panamint Mountains crossing at Wingate Pass, elevation nearly 2,000 feet. The first stop was at Bennett’s Wells where the muleskinners could rest and water the mules. The second stretch was the longest, 53 miles to Lone Willow, where only a few watering stations could be found. Granite Wells came next at only 26 miles. The last section was a desolate 50-mile trail of empty landscape and the most hazardous part of the journey, with no watering stations until the wagons reached Mojave. They journeyed 165 miles and 10 days through the bowels of an inferno.

The wagons were as tough as the muleskinners. Three wagons hitched behind the mules, with the first two wagons hauling the borax, and the third hauling water and feed. Constructed of aged oak, the beds of the wagons were 16-feet long, six feet in depth and four-feet wide. They weighed 7,800 pounds and cost a staggering $900. The iron wheels, fitted with split oak spokes, were eight-inches wide and one-inch thick. Three-inch square, solid steel bars were used as axle-trees. Carrying water, hay and food for the muleskinner and the swamper (who helped feed the mules and the muleskinner, and worked the brake on the rear wagon), the total weight pulled by the mule team was more than 60,000 pounds. Amazing, especially considering modern locomotive freight cars haul a capacity of 65,000 pounds.

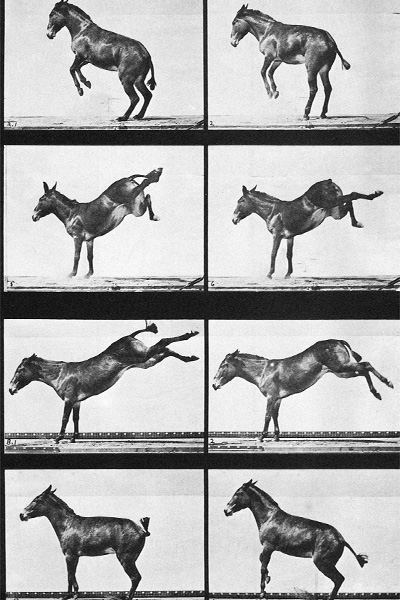

The 20-mule team consisted of 18 mules and two horses. The muleskinner’s single means of control was a jerkline that ran through the collar of each left-hand mule to the nigh leader, nearly 120 feet away. With pulls and jerks, he guided his team.

The first two mules, known as nigh leaders or left-hand leads, guided the team around curves, through steep grades and over mountain passes safely. The swing team-the next 10 mules-were the muscle of the group.

The pointers, the eights and the sixes mules stepped over the eight-foot chain hitch at nearly right angles in the direction of the turn. They would literally walk sideways as they went forward; keeping the chain straight until the entire team rounded the curve in the trail. The Wheelers-the two horses hitched nearest the wagon-were draft horses. The muleskinner often rode the back of the left-hand horse instead of inside the wagon.

The best place to get a firsthand history of the mule team legend is at the Twenty Mule Team Museum near Death Valley, in Boron, California. The volunteer-run museum exhibits displays of early borax mining operations, mule team memorabilia and artwork.

The 20-mule teams hauled borax through Death Valley’s hostile and barren terrain for only five years, with a proud unblemished record of never having lost a team or a load. Two muleskinners were murdered; one for his pay, the other by a swamper with a grievance. This record of service reinforces the formidable stamina, dependability and knowledge of the muleskinners. These foolhardy pioneers were the engines driving this mineral wealth to the success it has found in modern industry. The soap of yesterday is still a leading multi-purpose cleaner (even the Queen of Clean recommends it), and it may even prove to be an efficient energy source for fueling your car someday. From optical lenses to your porcelain enamel stove to the antifreeze in your car, this enduring symbol of the American West truly makes a difference in your life.

Clean-Burning Fuel Source?

Daimler Chrysler’s Town & Country Natrium is powered by clean-burning, borate-based fuel. The Natrium is 50 percent more fuel efficient than conventional gasoline engines and 90 percent cleaner.

So Death Valley may liven up a few folks’s lives after all, if this concept car fueled by glorified soap powder ever makes it to the market. Since Daimler Chrysler sold controlling interest for its auto unit to Cerberus Capital in May 2007 for $6 billion, this project has been put by the wayside.

Hopefully, nobody will forget this borax miracle.