The single element that both connected and distinguished David Milch’s HBO series Deadwood from the Westerns that preceded it was that the corrupt entrepreneurs, cast as classic villains, were placed at center stage in the saga.

Back when every Western had a villain, usually in a suit one size too small (think Brian Donlevy in Destry Rides Again), he would be trying to steal all the land or water rights or mining claims, or he would enlist a crew of bad guys to rustle cattle and rob stages. In Deadwood, we saw businessmen like Al Swearingen working hard to make a place of power in the community, only to see him become the victim of the far more powerful interests from outside the community; in his case, the Hearst machine.

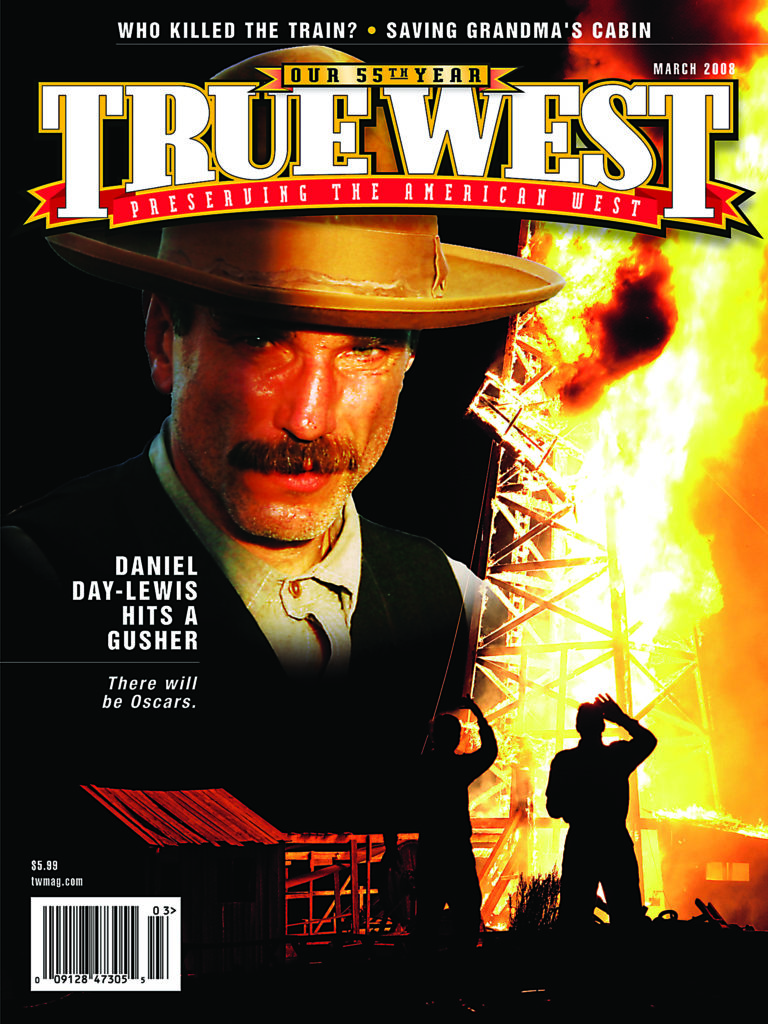

There Will Be Blood is a similar story, about a singularly focused man in the early years of the 20th century, Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis), who we meet at the beginning of the picture in a mine shaft—isolated, focused, digging in the dark for silver. All we need to know about Plainview we learn as we see him fracture his leg and still manage to crawl out to the surface.

Plainview does more than survive. He turns his attention away from silver to oil. By the time the plot is in full roll, we know that Plainview is in California, within driving distance of similar dragons who sniff the soil, like John D. Rockefeller and his company Standard Oil.

There Will Be Blood might have been the story of Charles Foster Kane (a Hearst surrogate) from Citizen Kane (1941) or Noah Cross, the financier and water baron of Chinatown (1974). Several writers have drawn comparisons between Kane and Plainview because of their wealth and terrible isolation, while others have mentioned how much Lewis seems to have adopted the speaking style of John Huston, who played Cross.

Some scenes in Blood are direct visual quotes from Huston’s film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), in which the younger John directed his father Walter (and allowed a tiny cameo for himself). We know from interviews that Huston and Sierra Madre played a major role in the genesis of Paul Thomas Anderson’s film and the construction of Lewis’ character.

Plainview himself, however, comes from the imagination of Upton Sinclair, and his 1927 novel Oil!, which, like several of Sinclair’s other novels, was designed to expose the seamier side of big business. Sinclair also introduced Eli Sunday, the young evangelist who arranges the sale of his parents’ land to Plainview, in exchange for a promise of his help in building a church. They become enemies in the film, each one working to humiliate the other.

Eli and Plainview don’t represent some philosophical disparity or clash of principles, they represent the same ambition, the same calculated and burnished hungers. But Sunday does not have the inner coldness that Plainview does; he can’t compete with Plainview’s misanthropy. Sunday may be playing his flock, but we don’t know that for a fact. We do learn that Plainview hates people as a rule; just before he kills a man, he confesses this hatred.

Anderson, who previously directed Boogie Nights, Magnolia and Punch Drunk Love, was not so interested in taking any hard and fast political position, nor was he interested in creating some kind of obvious schism between wildcat capitalism and grassroots evangelism, which some have suggested.

What Anderson is doing, and this is something new for the director, is sculpting a granite view of a man who, if he has any redeeming qualities, keeps them readily extinguishable. The son he adopts at one point, and then abandons when the child is left deaf by an accident, doesn’t offer any warmth to Plainview. His job, like everyone else’s in the story, is to illustrate Plainview’s innate emptiness.

Ciarán Hinds, who plays Plainview’s right hand man Fletcher, says “[The script] had a whole different feel to it. The themes were biblical and epic, about desire and revenge and emotions driven by ambition.”

The operative word here is biblical, because there’s something so dark and solemn about Plainview, he might have easily stepped out of the Old Testament. He’s someone who carries his curse like a calling card, identifiable by his drive to a fate defined by madness. You’ll even notice a bit of Isaac and Abraham in the relationship between Plainview and his son, particularly in the child’s-eye view of his mission-driven father.

Writers have been eager to attach meaning to Anderson’s story and to Plainview, but like his name, he’s just what he seems to be. If by the end of the film he has been reduced to a state of perpetual drunken dementia, it doesn’t represent a change in his basic nature, just another minor shift in who we saw in the dark hole at the beginning of the film.

Anderson has said he wanted his film to illustrate what happens to a man whose purpose is not being wealthy but to pursue a dream of wealth. The chase was the thing, and being wealthy, alone, in a mansion, waited upon by servants, as Plainview is at the end, is the final damping of the only authentic fire that drove men of this sort.

This is a movie that will likely draw an Academy Award to Lewis-a nomination at the least, if not a win. You can’t help but wonder if what makes Lewis so perfect is that Lewis, like Plainview, is a fixated actor, and that his renowned dedication to the parts that he chooses makes him similarly inaccessible to the actors around him.

In fact, one character in the story, Eli’s brother, was cut from the film when the actor left the picture, apparently because he felt intimidated by Lewis. (The mystery of Eli’s twin has been subject to a good deal of speculation on the Internet. Visit Idrinkyourmilkshake.com to see a funny website that addresses this and other issues of the film.)

Lewis’ dedication to Plainview works to the audience’s advantage, because he has to be fascinating. If we aren’t in awe of the man, we have little reason to engage with the story, since he exudes no warmness that will draw us to him or invoke our sympathies. Watching Plainview is like watching a documentary of a disaster. We sit, mute, wondering if the abyss hasn’t just turned its focus upon us.

Anderson can’t resist an exhausted apocalyptic ending, a stupefyingly banal murder that closes the chapter on a man who has come to haunt himself. As such, he represents a lost specter of the age of bare knuckle enterprise, a man who factors into the history of America and the people who made it.

Even Al Swearingen would have looked at Plainview and shuddered.