How the English-born, Civil War veteran’s career as America’s most prolific poet-stagecoach robber began on the backroads of California’s gold country.

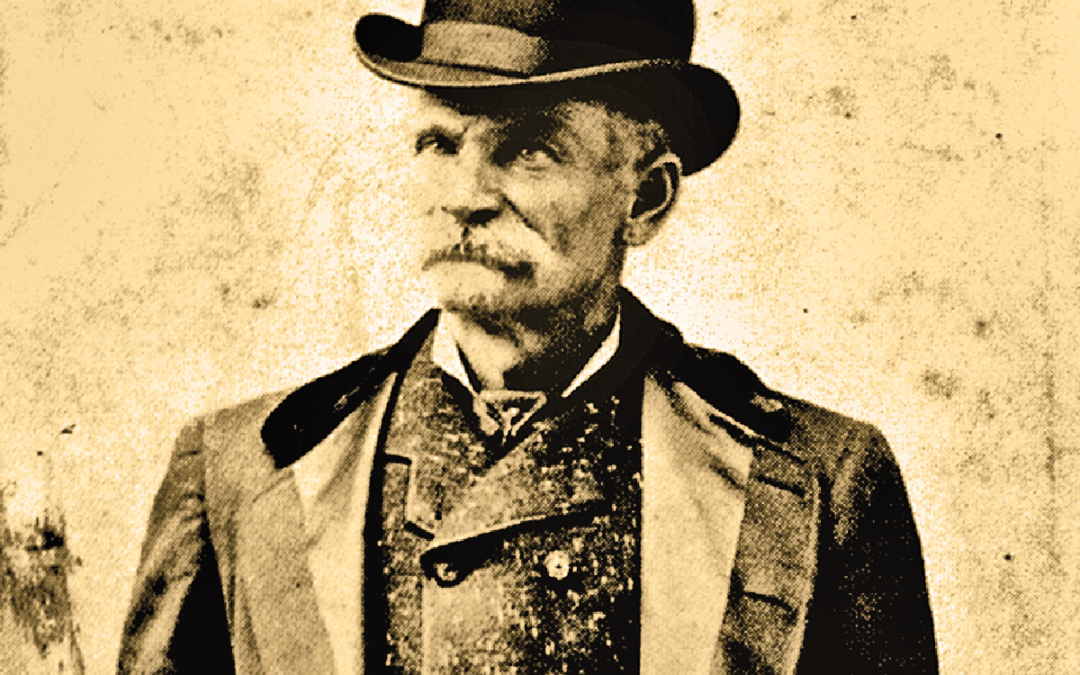

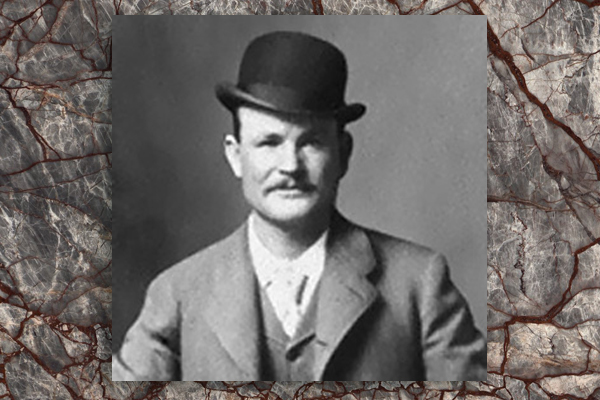

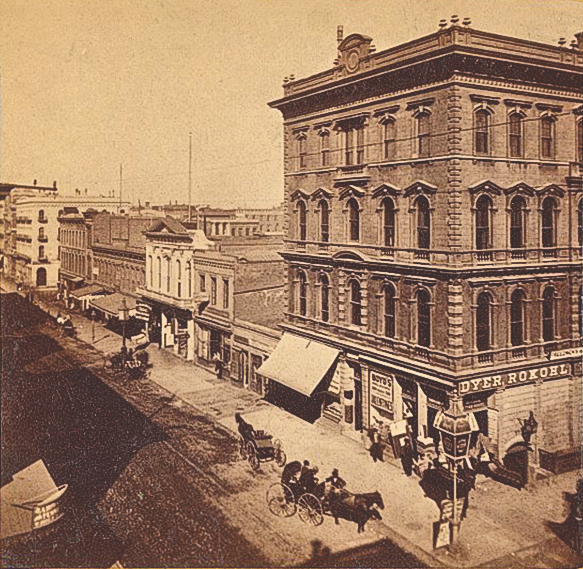

In San Francisco, Charley Boles became a new man. No longer was he a farmer in hobnailed boots, a rifleman in a muddy uniform or a gold hunter in a shabby miner’s frock. He suddenly began dressing in the height of fashion, sporting a salt-and-pepper wool suit with double-breasted coat, a silk tie with gold stickpin and a diamond ring on one finger, all topped off with a stylish bowler hat. He stepped briskly across the city’s cobblestone streets with a gold-headed walking stick swinging jauntily from his right fist. Though he was a loner, his gentlemanly manners and quick sense of humor soon attracted a small circle of friends and acquaintances. They ranged from the owner of his favorite restaurant, Jacob M. Pike, to the colorful and hugely popular fire chief of San Francisco, David Scannell.

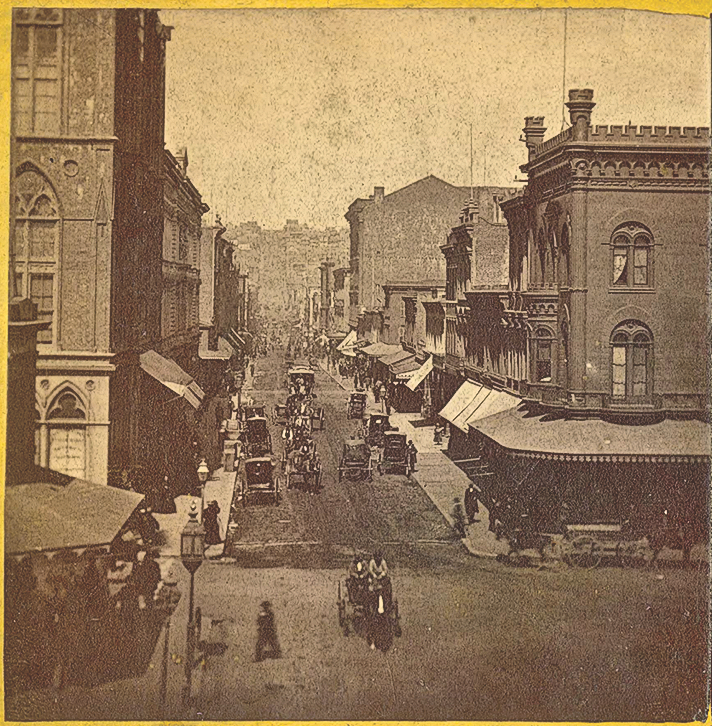

To San Franciscans he was Charles E. Bolton, but at various times he claimed to be C. E. Benton, Harry Barton and Charley Barlow. Boles told people that he was a prosperous stock speculator and mine owner with claims in the Sierra gold country and in Nevada’s Comstock Lode. He spent much of his time in what was called Pauper Alley—a section of narrow Leidesdorff Street, between California and Pine. It was situated just off Montgomery Street, which later became known as “Wall Street of the West.” Montgomery Street was—and still is—the center of San Francisco’s financial district. It featured the headquarters of major banks, mining companies, stock brokerages, real estate agencies and shipping corporations. Pauper Alley, so named after the silver market crash known as the Panic of 1873, connected San Francisco’s two stock exchanges.

Charley found it an exciting place, rife with the wild hope of quick riches. As Henry Brooks wrote in A Catastrophe in Bohemia a few years later, “Pauper Alley used to be an exhilarating sight. It was literally thronged—densely packed with noisy, excited, but good-humored operators; messenger boys tearing through the crowd, breathless, as though on errands of life and death…half the windows of the alley open, lined with spectators to see the fun; the saloons all thronged; a dense stream of thirsty humanity endeavoring to enter, and an equally dense stream seeking to make their exit; the bootblacks all scrubbing for their lives; their patrons enthroned, sleek, close-shaved, red-faced and jolly, for in Pauper Alley, prosperity patronizes the barber, bar, and bootblack… Groups of men studied [ore] specimens over their drinks, carried them in their pockets, and buttonholed their friends in order to exhibit them. There were samples of silver and gold bearing rock everywhere: in cabinets, in the exchanges and saloons, on the counters, in banks, and used as paperweights in the offices of mining secretaries.” He concluded by offering a description of its cash-hungry denizens, one that could have applied to Charley Boles: “If the truth must be told, they are a pretty hard lot in Pauper Alley.”

Several of Charley’s San Francisco comrades later told a newspaperman, “He was a man of prepossessing manners, fluent and extremely entertaining in conversation. He claimed to have been a captain in the late civil war, and loved to recount to listeners, some of whom were old soldiers, the events of his Gentleman military career.” Given that Charley was a brevet first lieutenant and a combat veteran, there was no need for him to exaggerate. Yet his apparent need to achieve success at any cost seems to have taken over all aspects of his life, including the retelling of his Civil War service.

Charley roomed at various city hotels and boardinghouses and frequently took trips out of town. He would leave his belongings behind in a trunk and tell his comrades that he had to make a visit to one of his mines. He would be gone for a week or a month, then return to his haunts in the financial district. Boles did not drink, frequent saloons and gambling houses, or patronize bordellos, of which San Francisco had scores. To all outward appearances, he was simply one of thousands of respectable businessmen in the bustling young city by the bay.

Charley Boles looked every inch the man he pretended to be—a prosperous mining investor in San Francisco.

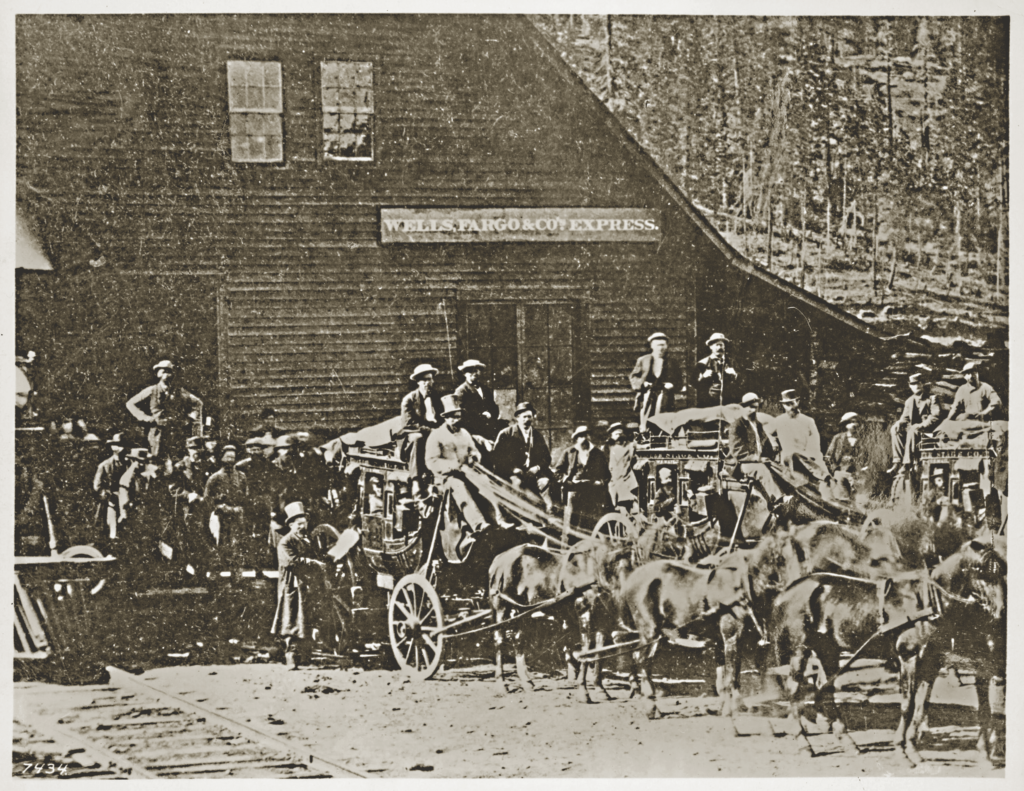

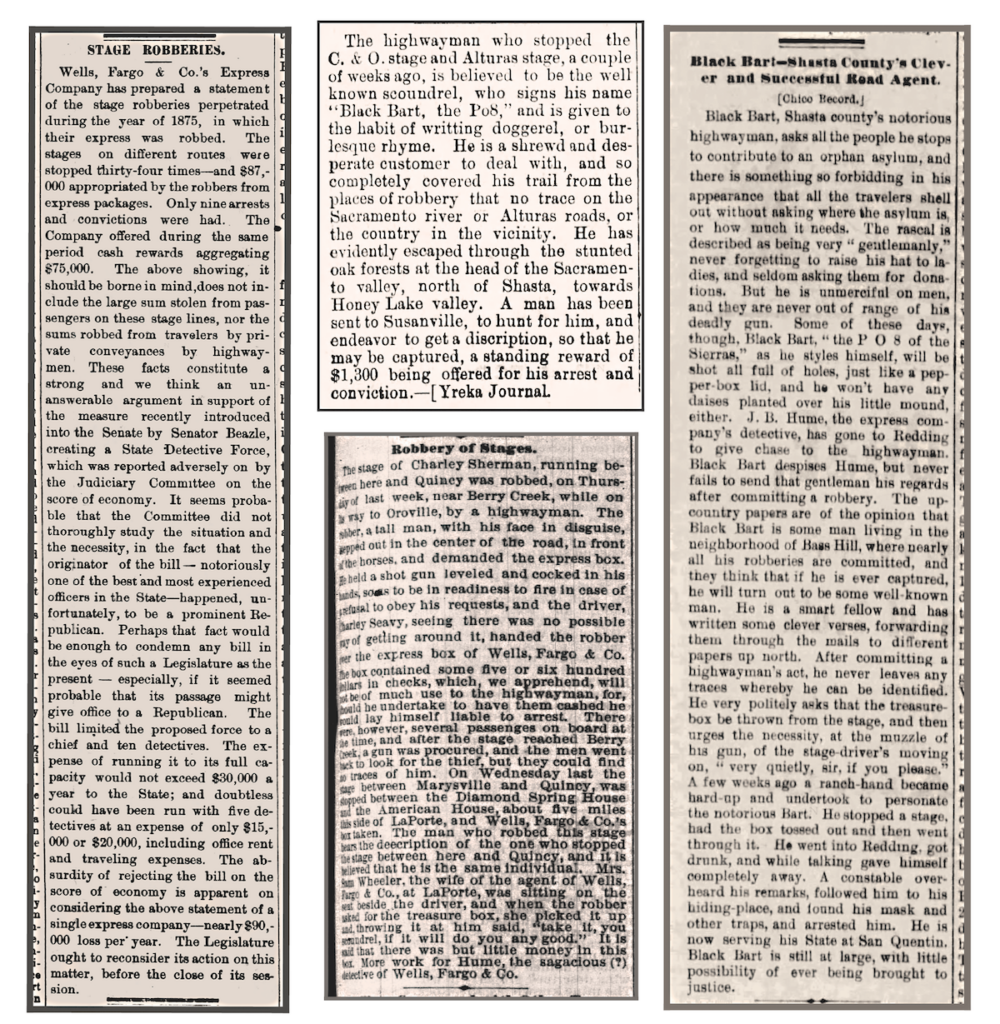

The reason for Charley’s sudden financial success would not become evident for years. But it began in the spring of 1875. In that era, San Francisco’s newspapers, ever engaged in bitter circulation wars, gave extensive coverage to crime reports. Sensational stories of murders, shootings, brawls and robberies filled their columns. Charley was a voracious reader of the San Francisco and Sacramento papers, and he followed the many accounts of stagecoach holdups. In November 1874 the dailies reported a double robbery on the stage road from Sonora to Milton. A gang of six masked highwaymen stopped the coach of John Shine, but he was not carrying an express box. They let him drive on, and when the next stage came along, they stopped it and looted the Wells Fargo shipment. It later developed that the gang was led by Ramon Ruiz, a notorious bandido. Several months later, in March 1875, Ruiz and two of his gang stopped a coach on Funk Hill, not far from Reynolds Ferry in Calaveras County. This time they escaped with more than $6,000 from Wells Fargo. That was a small fortune, worth more than $150,000 today.

Boles must have studied the news reports of the Funk Hill robbery. He knew the area well, because more than 20 years earlier, he had prospected for gold in Calaveras County. Charley then planned his first holdup carefully. He likely took a steamer across San Francisco Bay and up the San Joaquin River to Stockton, then walked 50 miles to Funk Hill. Mimicking the Quaker guns he had seen in the Civil War, he whittled tree branches into mock rifle barrels and cleverly placed them amid the roadside rocks and brush. On July 26, 1875, he stopped John Shine’s coach and stole Wells Fargo’s treasure, then hiked out of the mountains and back to San Francisco. Years later, Boles recalled that he first headed south, forded the San Joaquin River near Grayson, then crossed the Coast Range through Pacheco Pass. With his Henry rifle slung over his back, he looked like a common traveler or hunter. In rural California in that era, sheriffs and constables were few and far between, and many men carried firearms for self-protection. On the way, he stopped at a house to eat and rest. There, as he later told a newspaperman, “a woman wanted to buy his gun.” Charley responded that he “would not sell it, but would give it to her.”

She replied, “No, I will buy it.” The woman offered $10 and handed him a $20 gold piece. Charley gave her in change a $10 bill he had stolen from the express box. Then he continued on foot to San Jose and up the San Francisco Peninsula to his boardinghouse in the city. His 250-mile walk, while impressive, was nothing compared to the marches he had made in the Civil War. Boles had wisely chosen to avoid riding horseback. In that era, everyone knew horseflesh, and witnesses often paid more attention to a saddle animal than to the man riding it. Therefore, a mounted fugitive was easier to identify. And Charley’s ability to walk great distances made it possible for him to avoid well-traveled roads and trails and helped him evade capture for years to come.

True West Archives

Boles started out slowly as a road agent. During the next two years, he held up only three more stagecoaches: Mike Hogan’s stage from North San Juan in December 1875; A. C. Adams’s coach on the Oregon-California line in June 1876; and Ash Wilkinson’s rig on the Sonoma Coast in August 1877. By that time, he had found a clever moniker for his newfound identity as a lone highwayman. One of his favorite short stories was “The Case of Summerfield,” written by a San Francisco lawyer named William H. Rhodes, who used the pseudonym “Caxton.” “The Case of Summerfield” was an early work of science fiction, about a man who discovered a way to set water on fire, and anyone obtaining his secret could destroy the world. It was first serialized in the Sacramento Union in 1871 and then widely reprinted by newspapers throughout the U.S. and even in Australia. In 1876, “The Case of Summerfield” was released by a San Francisco publisher as part of an anthology of Rhodes’s works. One of several villains in the story was a stage robber named Bartholomew Graham, alias Black Bart.

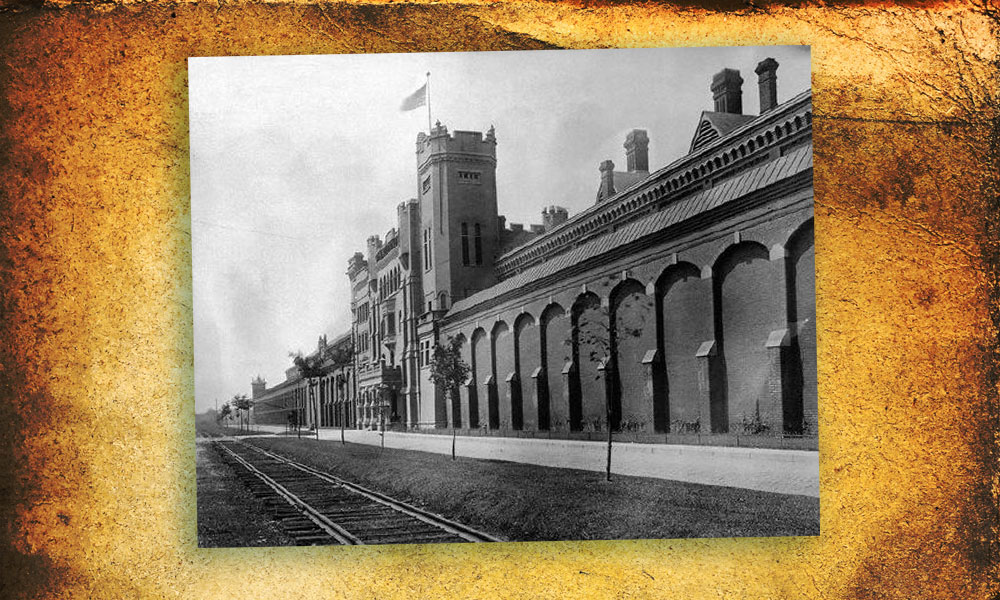

In Charley’s first four robberies, he took only about $600 from Wells Fargo. That was hardly enough money to support his gentleman’s lifestyle over a period of two years. However, in all of the holdups, he also stole the U.S. mail. As Wells Fargo detective Jim Hume later said, “Black Bart told me that in his first 27 robberies he realized more from the mails than from the express.” Given Boles’s comfortable situation in San Francisco, he must have taken a few thousand dollars from the mailbags. With this money, he lived in quiet prosperity in the city. Charley also made numerous visits by train to Sacramento, which he apparently used as a base for some of his stage-robbing expeditions. As a Sacramento journalist later reported, “His face is well known at the depot dining rooms, for he traveled back and forth from San Francisco frequently.”

In July 1878, Boles made one of his customary trips out of San Francisco. He crossed the bay by ferry and then boarded an eastbound railroad train in Oakland. In his bedroll, he concealed a double-barreled sawed-off shotgun, which he broke down into two pieces, barrel and stock, for ease of carrying. At the depot in Sacramento, he changed trains and headed to Oroville, 70 miles north. Oroville, the seat of Butte County, was a bustling Sierra foothills town of 1,500 people that served as a major shipping point for gold from the Northern Mines. Charley remembered Butte County well, for it was there that he had first dug for gold after arriving in California in 1850. From the train depot in Oroville, he walked northeast 20 miles into the mountains and made camp in the brush a mile east of Berry Creek. He knew that rich shipments of gold were regularly sent to Oroville by stage from the mining town of Quincy, high in the Sierra Nevada.

Courtesy California Historical Society

Early in the morning of July 25, 1878, the Oroville-bound coach rolled out of Quincy with Charles Seavy at the reins. His three passengers settled in for a long ride. The remote, winding wagon road from Quincy to Oroville, now Highway 162, was a one-day, 65-mile trip. At three o’clock that afternoon, as Seavy carefully descended a hill a mile outside of Berry Creek, Boles suddenly jumped in front of his team.

“Throw out the box!” Charley demanded as he covered the jehu with his shotgun.

Seavy was so startled, and so busy reaching for the Wells Fargo box, that he did not get a clear view of the highwayman. Later, when his fright wore off, he amusingly recalled that the gun barrels looked three inches wide and that he had “a vivid remembrance of the appearance of the 19 buckshot at the bottom of the shotgun.” The passengers, however, got a good look at the road agent. They later said that he was “a tall, slim man, with iron gray hair and whiskers, probably full beard, vest and shirt, Kentucky jean pants and long-legged boots. He was armed with a shotgun and had a revolver in his belt. His face was concealed with a white cloth.” Although in prior holdups Boles had worn a flour sack over his head, this time he only covered his face.

Seavy quickly tossed down the Wells Fargo strongbox, which held $400 and a $200 diamond ring. Then Charley called to the jehu, “Drive on.”

As the coach rattled off, Boles broke open the box, removed its contents, and left inside a scrap of brown paper with a bit of doggerel, each line written in a disguised hand. He had apparently composed it in his camp the night before.

At the bottom he signed it,

“Black Bart, the Po8.”

Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow.

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat,

And everlasting sorrow.

Let come what will, I’ll try it on,

My condition can’t be worse.

And if there’s money in that box,

Tis munny in my purse.