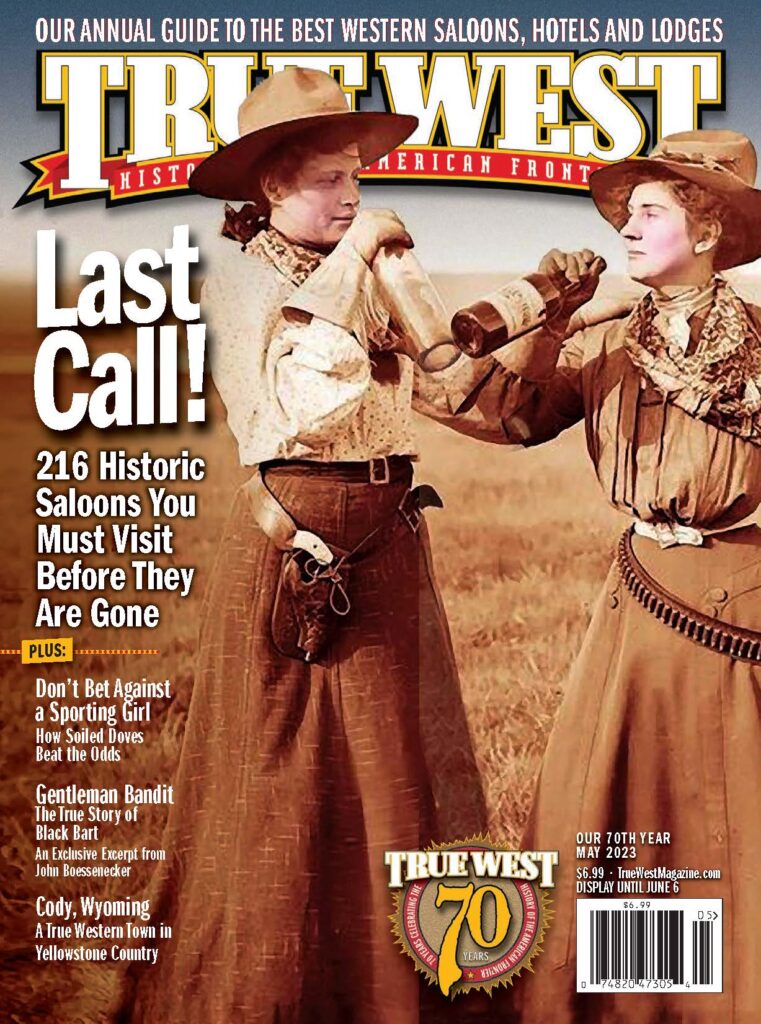

How soiled doves tried to beat the odds against hypocrisy and politicians

For several decades, Hollywood has had a fine time portraying shady ladies of the past. From the illustrious Miss Kitty of CBS’s Gunsmoke, to the disreputable wenches on HBO’s Deadwood, viewers have been given a taste of how prostitutes lived and what they went through. Unfortunately, neither of these shows, nor others like them, portray the prostitution business as it really was: a vicious cycle wherein women with no other way to make money broke the law to sell their bodies for sex, paid off numerous government officials in order to remain in business and died unrecognized for their unseen, unappreciated good deeds. In reality, such women were viewed as debaucherous troublemakers, home wreckers and fallen women who lured young men into their lairs and did unspeakable things with them for cash. Rarely did someone happen to point out that the law’s habit of collecting money from business establishments that were illegal was in itself, a crime.

The politics of prostitution were very real during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Brothels were outlawed, and the women working in them paid for fines, fees, business and liquor licenses. Many also paid higher property taxes than other legitimate businesses. Talk was constant about closing down bawdy houses, but most cities were hesitant to try surviving without the monthly income generated from the demimonde. The money was mighty handy for supporting schools, hospitals and churches—the latter which soiled doves were sometimes forbidden from attending. Throw in a healthy dose of city governments who took the women’s money, failed to assist them when they were in need, publicly insulted and laughed at them, and forgot them when they died, and here was hypocrisy at its finest. It was, after all, easier to reap profits from prostitutes than it was to actually treat them as equals and help them become first-class citizens.

Prostitution in America goes back a long way, even before city governments found a way to prey on fallen women and profit by it. Back in 1805, when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark came west, they found that Native women appeared more equal in status to their male counterparts. And although Native leaders sometimes offered their wives or daughters as gifts or trade to Anglo men, doing so was considered an honor among the tribe. There was no disgrace, no backlash. Not until settlement of the West by White pioneers began was the buying and selling of sex considered naughty. In 1863, Montana’s first newspaper editor, Thomas Dimsdale, was in Virginia City where he observed the numerous “women of easy virtue” who were “promenading through the camp.” A captivated Dimsdale described them in great detail, as well as the dance halls where they worked, and their customers. From all appearances, the ladies received “fabulous sums for their purchased favors,” according to Dimsdale. But what many women actually did with their money has often been buried under objections to their presence.

The Whore with a Heart of Gold

Hundreds of harlots deserve long past-due credit for their contributions to schools, churches, the poor, the homeless, needy children, injured and sick laborers, and countless others. Stories about such deeds are numerous. During the 1880s, for instance, when it was finally decided that a church should be erected in Kingston, New Mexico, Madam Sadie Orchard and her friends passed a hat among the saloons and brothels for its construction. The ladies received gold nuggets, jewelry and cash amounting to $1,500. At Leadville, Colorado, in 1881, newspapers questioned Madam Mollie May’s motives after she took in a baby while the child’s destitute mother contacted relatives for assistance. One newspaper also interviewed Mollie, who angrily reminded the general public of all the charities she donated to on a regular basis.

Some women donated property as well, or at least tried to. Beginning in 1891, longtime madam Anna Wilson of Omaha, Nebraska, tried to lease her posh, 37-bedroom parlor house to the city to use as a much-needed hospital. City officials mulled the offer for several weeks before ultimately declining the offer. Anna did not give up; over the next two decades she gave an elaborate fountain from her private home to a local park, donated $300 to the “Child Saving Institute,” and, in 1911, offered her parlor house for lease once again—this time with the stipulation that the building would bequeath to the city after her death. Omaha officials finally accepted her offer, and the wealthy madam died soon afterwards.

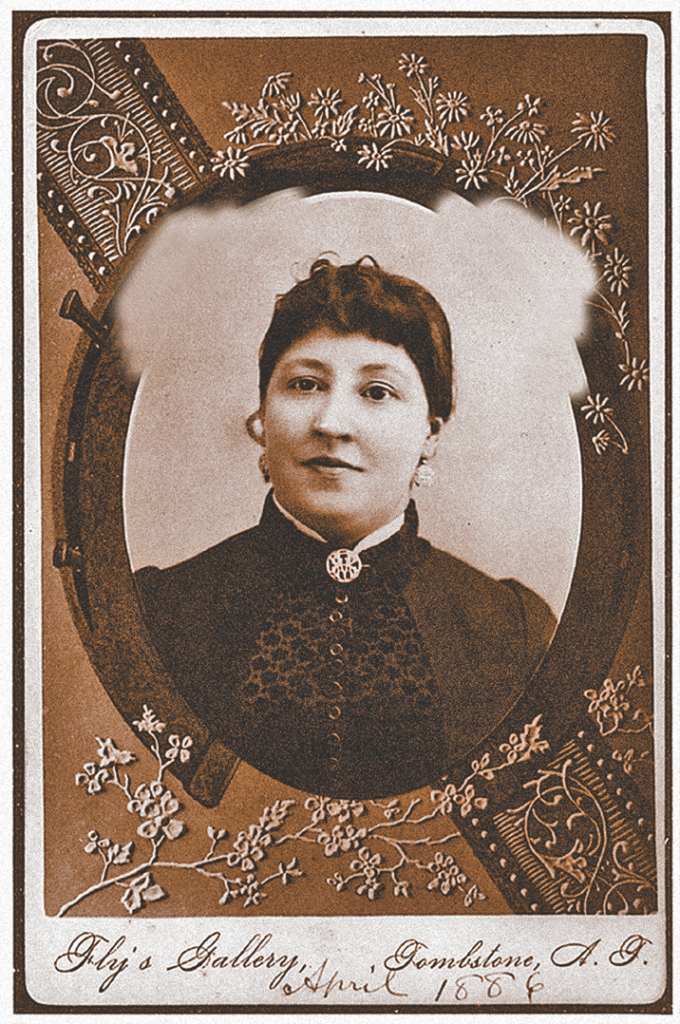

Many ladies of the red-light occupation willingly shared their wealth, sometimes by law, sometimes by unwritten law, and sometimes on their own. In Tombstone, Arizona, funding for the Episcopal church was contributed by local gamblers, saloons keepers and the bawdy women of the town. That did not stop respectable women from soliciting for additional donations from prostitutes. One of them, an employee of the infamous Bird Cage Theater, exacted her own revenge. “Them women always looked down their noses at us—excepting when they needed some money for a charity,” she recalled. “Then they’d come down and ask us girls. Well, I always donated, but I got my licks in doing it. I had found out from a [sic] old lady that if you used a certain size coin and placed it just right—then you wouldn’t get pregnant. Well, when I used them coins, I laid them on the table in my room. Then, when the society ladies come down for a donation, I give them the coins on my table.”

The Ladies Contributed More Than Money

As much as wanton women were a soft touch for the down-and-out, they did have a motive. Simply put, if their hometowns did not do well, the ladies themselves did not do well. Many madams simply took charitable matters into

their own hands on behalf of their cities, but also their clients, friends and even local children. Colorado City, Colorado, madam Laura Bell McDaniel gave her blind friend, Dusty McCarty, a job bartending. During the early 1900s, Madam Lea Perry of Silver City, New Mexico, was remembered as a kindhearted woman who purchased coats for poor children and grubstaked local miners. In Jerome, Arizona, Madam Lil Douglas and her girls bought presents for the local children at Christmas. And let’s not forget Silver Heels, the legendary dance hall harlot of Colorado who risked her own life and became permanently pockmarked while helping during a small-pox epidemic.

Perhaps one of the best benefactors in the West was Laura Evens of Colorado, who was the reigning madam of Salida by the early 20th century. Because of her, during the Great Depression, food baskets were found on the doorsteps of families with children. Coal was mysteriously delivered to those in need, free of charge. A church in town received

a new roof. Railroad men who were hurt on the job would receive less strenuous employment offers while they recuperated. One man recalled recovering from an injury, and being offered a job selling newspapers at unusually high pay. “I didn’t learn until long after Laura died that she paid the storekeeper for my salary for more than a year while I got over my pain and learned to use what was left of my hand,” the man later recalled. Others remembered how Laura paid young boys to run her errands, and instructed them to tell their mothers they “earned the money in honest work for a stranger.” Abused housewives were sometimes sheltered by Laura, who refused to let them work for her. “I doubt if anybody will ever know how many people Laura helped,” said one Salida politician in later years. “She was an entire Department of Social Services, long before there was such a thing.”

The Hypocrisies Against Harlots

Prostitutes and madams were only publicly recognized for their good deeds now and then. At Helena, Montana, in 1865, a local alderman, R.H. Howrey, blatantly lectured that “all sin and fault is laid at the doors of the women; no charity is expressed for them.” Howrey also recognized that the prostitution “is an evil arising from the vile passions of men that made [the women] what they are.” Yet his truth fell on deaf ears, no doubt because the city government was already scheming to make the demimonde their own cash cow in the way of exorbitant fines and property taxes.

By the 1890s, nearly all cities had instituted systems that allowed them to collect money from the red-light ladies. Policemen whose beats included the “restricted district” quickly figured out how to extract more cash by extorting “protection money” from the women. In some cases, the madams also supplied complimentary liquor and girls to law enforcement and city officials. Other times, police willingly aided the ladies in exchange for pay. Such was the case at Maggie and George Woods’s Red Light Saloon in Caldwell, Kansas. In 1880 the couple hired police officer George Reed to perform various odd jobs that likely included serving as a bouncer. Ten years later, the McCook Tribune revealed that certain “high license” brothels in far-off Lincoln, Nebraska, were allowed to sell liquor without being required to purchase a license or contribute to the local school fund.

It was no secret that women of the demimonde were fully expected to contribute money to the local nonprofits. In 1893, Sheriff Hi Wilson told the women working above the Bennett Avenue saloons in Cripple Creek, Colorado, that they must relocate one block south to Myers Avenue. There, he promised the ladies, they could run their businesses freely as long as they paid their fines and donated to the local charities. Although some cities did establish rescue missions for wayward girls, they relied solely on the women to volunteer to be reformed. When Florence Roberts approached a policeman in San Francisco about helping a teenager who was being forced by her own father to sell sexual favors, the officer responded, “I can’t interfere. The man has a license, his daughter isn’t of age, he’s her legal guardian.” The girl’s father was not the only one making money off women; in Arizona, California, Montana, Oregon and other states, prominent businessmen, including clergymen, were sometimes identified as the actual owners of brothel properties.

The best example of hypocrisy in government was the “Stockade” in Salt Lake City, Utah. In 1907, city officials approached Ogden madam Dora Topham, aka Belle London. Dora had long been known as a most charitable woman who frequently reached out to women and children in need. The city, under Mayor John Bransford, offered Dora an amazing business deal: the madam could pick out a sizeable piece of property in Salt Lake City on which to construct a large, legal red-light district with parlor houses, cribs and a saloon—enough to house several hundred prostitutes. Dora accepted.

Despite protests by newspapers and citizens, the Stockade was constructed within about a year, and a large wall was built around its perimeter. But the operation was immediately besieged with problems, including busting secret holes in the wall and the presence of an underage girl. Accusations were made, lawsuits were filed, and Dora was served to appear in court—by the very city who had hired her for the job. The genteel lady suffered myriad illnesses at the mere thought of being jailed as newspapers and the general public blamed and shamed her. Among those to defend Dora was Reverend Noble Strong Elderkin, who urged “the repeal of the laws against vice and lawbreaking to save citizens from hypocrisy,” and “denounced Salt Lake for its discourteous treatment of Belle London.”

Six months later, after having her say in an interview with the Salt Lake Herald, the charges against Dora were dropped. There was another attempt to reopen the Stockade as Dora tried to ingratiate herself to the good women of Salt Lake City and Ogden, but it was no good. The Stockade closed permanently in 1911 as Goodwin’s Weekly newspaper declared that Dora had obviously been railroaded. Even her hometown of Ogden turned on her, and in 1917 she moved to her daughter’s home in California and changed her name. The Ogden Standard Examiner brought forth her shameful past by calling her Belle London when she died in 1924. Thankfully, Dora’s friend, D.W. Brown, wrote a letter to the editor pointing out the woman’s many kindnesses and how well her daughters turned out. “If you wish to ask any questions concerning this account, drop me a card and I will call at your office,” Brown wrote.

The Red Light Abatement Act

Frontier prostitution, as it was known, was drawing to a close by 1913, when the state of California introduced the Red Light Abatement Act which, it was hoped, would put an end to the prostitution industry once and for all. Similar acts would be filed in other states over time, but the problem was that nobody had anything to offer in the way of rehabilitation or finding respectable jobs for prostitutes. While male brothel owners might certainly find other business endeavors and remain successful, prostitutes would be relegated to menial, low-paying jobs. Many of them would remain unemployed, or they were fired, if their prospective employers became aware of their shady pasts. Single and widowed women, and mothers especially, would suffer under impoverished conditions—which was the biggest reason most of them became prostitutes in the first place.

Most of the 138 women who were brought into court after San Diego’s bawdy Stingaree District was closed that November, did not believe the local Purity League’s promise to help them. The ladies had heard it before, and many of them refused to even give their birth names. One 28-year-old prostitute told officials that she “would be glad to quit the sporting life if you could find a job which would enable me to earn enough to meet my expenses. I have a crippled mother and a young sister to support.” The woman went on to explain that she had worked legitimate jobs, “but the wages were not enough to keep me alone.” The officials had nothing to offer in response.

Courtesy True West Archives

Death in the Demimonde

Today, only a handful of graves for wayward women can be found across the West. More often than not, their relatives, if they were found, were shocked to discover what the women had really done for a living. Many relatives refused to have anything to do with the disposal of the girls’ bodies. This is what happened to Madam Pearl DeVere when she died in Cripple Creek in 1897. Pearl’s sister duly came from Indiana to claim the body, found out that Pearl was not the hat or dressmaker she said she was, and immediately boarded the next train out of town.

Redemption for prostitutes and the lives they led was sometimes granted after they died. When Mollie May died in 1887, a respectable woman, Mindy Lamb, insisted on attending her funeral. Some years before, Mollie had stopped Mindy on the street and offered her condolences for the murder of Mindy’s husband, Lewis. The two formed a friendship which was apparently kept quiet until Mindy announced she was going to Mollie’s services. Also, Mollie’s obituary noted that “she was a woman who, with all her bad qualities, was much given to charity and was always willing to help the poor and unfortunate.”

Even madam Anna Wilson was praised for her efforts to encourage prostitutes to “leave the life of the red light,” as well as leaving many donations to Omaha’s churches, child services and hospitals when she died. The madam’s will also decreed that she be buried under nine feet of concrete, lest anyone change their mind about where her final resting place should be. In the case of Sammie Dean, a red-light lady from Jerome, Arizona, who was murdered in 1931, her family did claim her body, and took it back to Texas to be interred in the family plot.

Other women from the demimonde were not treated so kindly upon their deaths. When Tessie Wall, the scrappy Irish madam of San Francisco died in 1932, some of her money and property was willed to the ten relatives who survived her. Most of it, however, went to the executor of her estate: Police Capt. John J. O’Meara, whom Tessie had known for nearly forty years. There was little interest in the madam’s furnishings, which were considered rather “bizarre” and garish. When her jewelry, fine art, bedroom sets, furnishings and a China set formerly owned by William Rockefeller were put up for auction, few appeared to bid. Most items sold at amazingly low prices. “Most interesting, I found,” noted a reporter from the Oakland Tribune, “were the men present who watched the sale and said nothing.”

Likewise, Dell Burke of Lusk, Wyoming, was well known for her “Yellow House,” the brothel she ran for many years. Dell died in 1980, long after Lusk’s other shady ladies had moved on. But even at that late date, few wanted to have anything to do with Dell, including her family. A call to a relative for the writing of Dell’s obituary was not returned. When her descendants were finally located, they declined to come to Lusk and simply ordered Dell’s body to be cremated, even though her estate was worth over a million dollars. And in 2005, after a long search for the burial records of the generous madam Rachel Urban in Park City, Utah, historian Gary Kimball finally located what many historians had not: the records for Rachel were well hidden, and certain others had been “erased or half entered.” If not for Kimball’s research, Rachel, who died clear back in 1933, might have been forgotten. But she is certainly remembered now.

The Terrible Cost of Living for Prostitutes

25¢: Cost for the services of a Chinese, Black or American Indian girl in Tombstone, Arizona, circa 1880-1900

25¢ to 50¢: The price of a drink in Virginia, City, Montana, in 1860

50¢ to $10: The average price for a “trick” during the 1880s

50¢: Cost for time with a Mexican prostitute in Tombstone between 1880 and 1900

75¢: Cost for time with a French girl in Tombstone in 1880-90

$1: Amount soldiers at Arizona’s Fort Whipple paid for sex in 1880

$1: The cost of a four-ounce glass of beer in Denver in 1891

$5, plus half their earnings: The monthly rent paid by Mattie Silks’ girls in Denver during the 1880s

$5: The fine prostitute Ranche Belle paid at Virginia City, Montana, in 1865 for using bad language

$7: The monthly fine paid by Laramie, Wyoming, prostitutes between 1878 and 1880

$15: The weekly rate of a two-room crib in Denver in 1882

$18: The monthly fine for running a brothel in Wichita in 1873

$10: Cost of a visit to a plush parlor house in Tombstone in 1880-92

$20: The fine Frankie Bell paid at Dodge City in 1877 for cussing at Wyatt Earp (Earp paid a $1 fine for slapping her)

$25: The monthly fine paid by Phoenix, Arizona, prostitutes in 1940

$30: Cost to spend the entire night in a Tombstone bordello during the 1880s-90s

$50: The fee paid to city physicians who examined prostitutes in Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916

70: Number of customers some women saw in an average payday at the mines

$150: Weekly salary a prostitute could make in Tombstone during the 19th century

$175: The monthly rent for a parlor house at Salt Lake City’s “Stockade” in 1908

$3,000: The cost to purchase a Chinese prostitute in San Francisco in 1898

$100,000 to $150,000: The value of the estate of Madam Cora Phillips of Los Angeles when she died in 1891

Cities Whose Business Owners Paid Little or No Business Taxes Due to Income from the Demimonde

- Salt Lake City, Utah

- Silverton, Colorado

- Wichita, Kansas

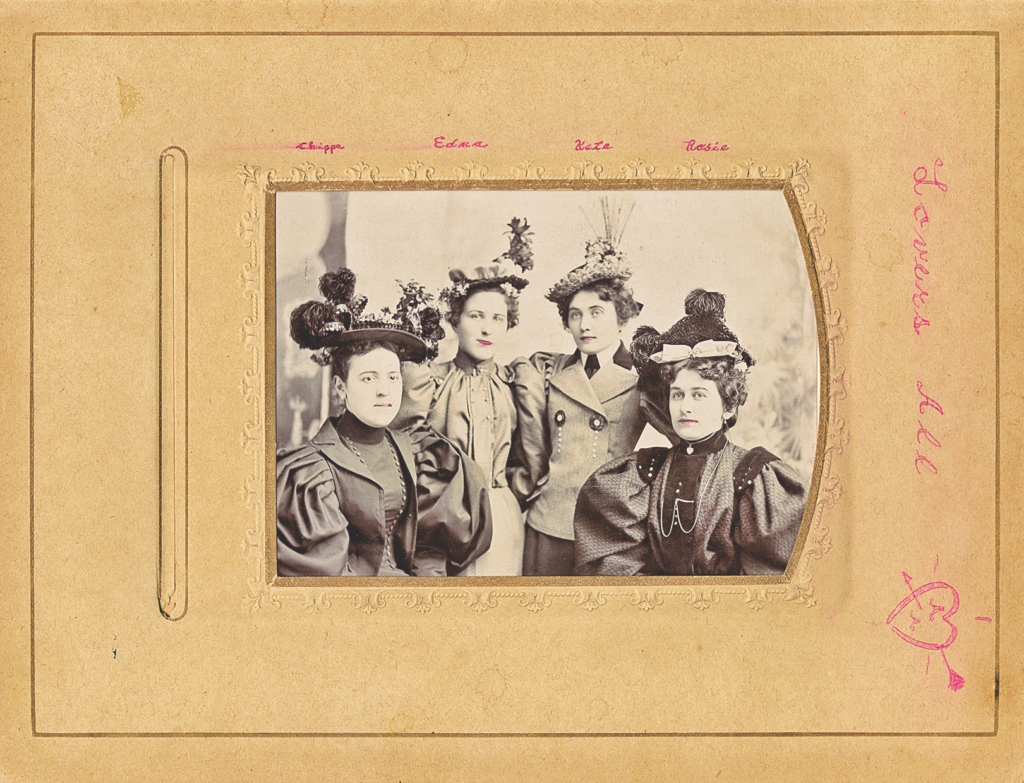

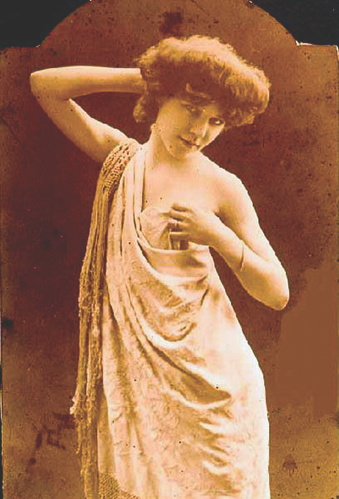

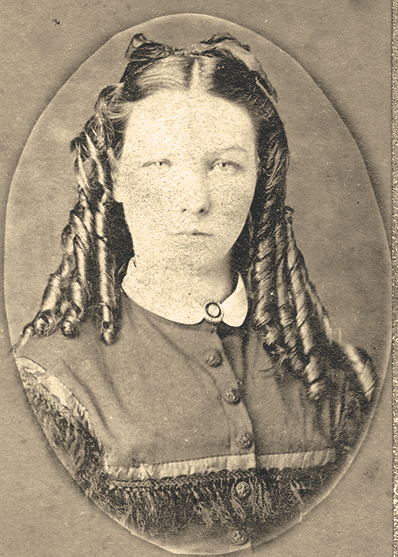

The Faces of Prostitution

All Images Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted

Courtesy Idaho Library Special Collections

Courtesy Idaho Library Special Collections