A journey on the historic route goes through the heart of traditional Lakota and Cheyenne hunting areas.

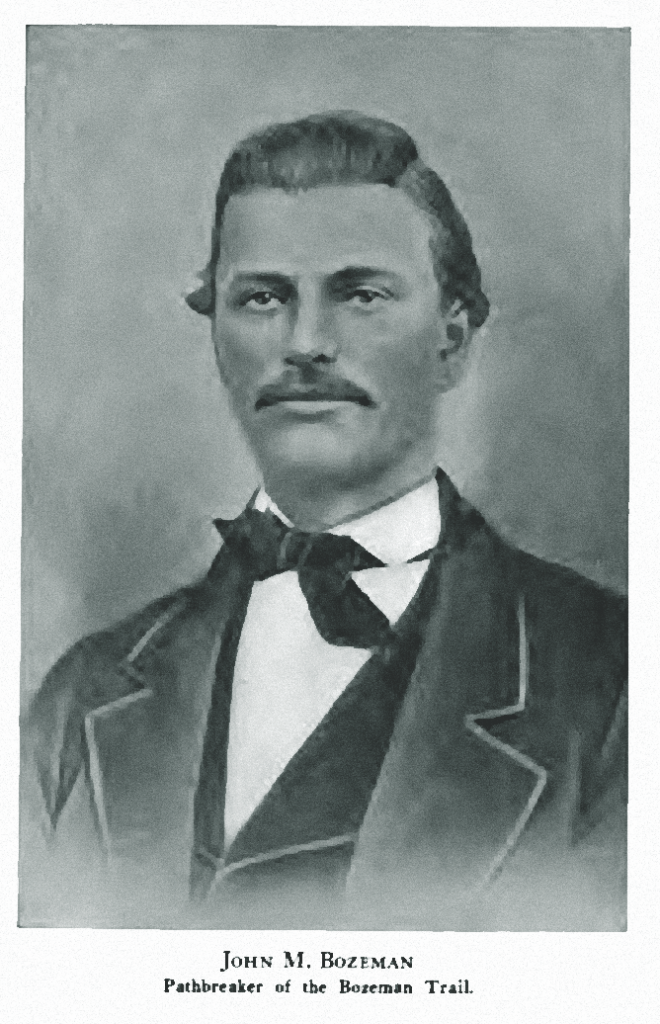

Long before John Jacobs and John Bozeman rode across what is now Wyoming’s Powder River Basin toward Fort Laramie in 1863—finding a route that brought gold seekers to western Montana—native people lived in the area.

Bozeman and Jacobs traveled from western Montana, where gold had been discovered in Alder Gulch giving rise to Virginia City. After crossing the pass later named for him, Bozeman followed the Yellowstone River through Crow lands, and then turned to the southeast, skirting the flank of the Bighorn Mountains and across the Powder River Basin. Familiar with Fort Laramie, the major military post in the area, he knew people would want to get to the new gold strike in Virginia City as quickly as they could. By leading those seekers over his route, he could gain wealth for himself and give the new miners a better shot at riches for themselves.

the Bozeman Trail, including the Battle of Red Buttes. Courtesy Candy Moulton

Hunting Grounds

The challenge of the new route lay not with the terrain, but rather with those people who already lived there, especially in the first couple of hundred miles from Fort Laramie to the north end of the Bighorn Mountains. Among the residents of the region were northern groups of the Lakota tribes, including Miniconjou, Oglala and Hunkpapa Lakota, as well as many Cheyennes.

Jacobs and Bozeman went right across the heart of the prime hunting lands for these tribes. The route the gold hunters would follow along the eastern Bighorn Mountains was a well-known Indian trail known as the Trail Going South.

In addition to their longtime use of the area, the Lakota and Cheyenne people understood they had a right to live and hunt in the region, codified by the 1851 Horse Creek Treaty that was signed by some tribal headmen. Lakota and Cheyenne tribe winter counts, according to the tribal historic record and the oral storytelling tradition, show that the people camped and lived in the area from the Black Hills to the Bighorns. They often spent summers closer to the Bighorn Mountains and were routinely engaged in raids and warfare involving the Crow or Apsaalooke.

Donovin Sprague is a Lakota historian whose family was one of those significantly involved with events in the region during the 1860s. His great-great grandfather was the Lakota headman Hump, and he was related to Crazy Horse and to the Cheyenne leader Morning Star, also known as Dull Knife.

Before Bozeman and Jacobs attempted leading their first wagon train along what became the Bozeman Trail, the families of Hump, Crazy Horse and Morning Star had moved to camps along the Tongue and Powder rivers. Their initial purpose was to keep the Crows farther north. But with the influx of gold seekers, the focus turned to the Bozeman Trail. Sprague says from their camps at Devil’s Tower and along the Powder and Tongue rivers, everything converged on the trail. The Lakotas and Cheyennes moved south along the trail, establishing camps in areas west of Kaycee and in the Crazy Woman Creek area. The intent of the tribes was to target travelers on the Bozeman Trail and “wreak havoc any way [they] could,” Sprague says.

Danger on the Trail

Other outside influences on the northern tribes also affected Bozeman Trail travel. In November 1864, Col. John Chivington and Colorado Volunteer troops attacked Black Kettle’s camp at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. In the massacre, Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho people were killed, many of them elderly, women and children.

Retaliation attacks began almost immediately. In January 1865, tribal fighters attacked Julesburg, Colorado, and began raids along the South Platte River. As spring and summer advanced, gold seekers set out again on Bozeman’s Road to Virginia City. Simultaneously, the tribes in the area began planning a major revenge raid, which they carried out in two separate events, both on July 25, 1865. Early that morning they lured soldiers from the 11th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry and Lt. Caspar Collins of the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry from the post at Platte Bridge, ambushing the soldiers, killing some, including Collins, and forcing the others to retreat to the post.

Later in the morning a supply wagon train led by Sgt. Amos Custard, traveling east from the Sweetwater Station, topped a hill just west of the Platte Bridge post, and the soldiers were immediately overrun by tribal fighters. Within a couple of hours, Custard and 20 men with him were dead.

Hump and the Cheyenne war leader Little Wolf planned and executed the attack with Crazy Horse, Young Man Afraid of His Horses, Cloud and other prominent fighting men involved in the actual attacks as decoys or fighters. The two battles that day were significant victories for the tribal fighters.

Fort Laramie to Sheridan

The route Bozeman’s wagon trail covered left Fort Laramie on the main Oregon Trail path, and split to the north at Fort Fetterman, northwest of Douglas. To protect the trail, the U.S. Army established three forts in that Lakota and Cheyenne country: Fort Reno in the heart of Powder River Basin, Fort Philip Kearny north of Buffalo Creek, in Buffalo, Wyoming, and Fort C.F. Smith, beside the Yellowstone River at the edge of Crow territory.

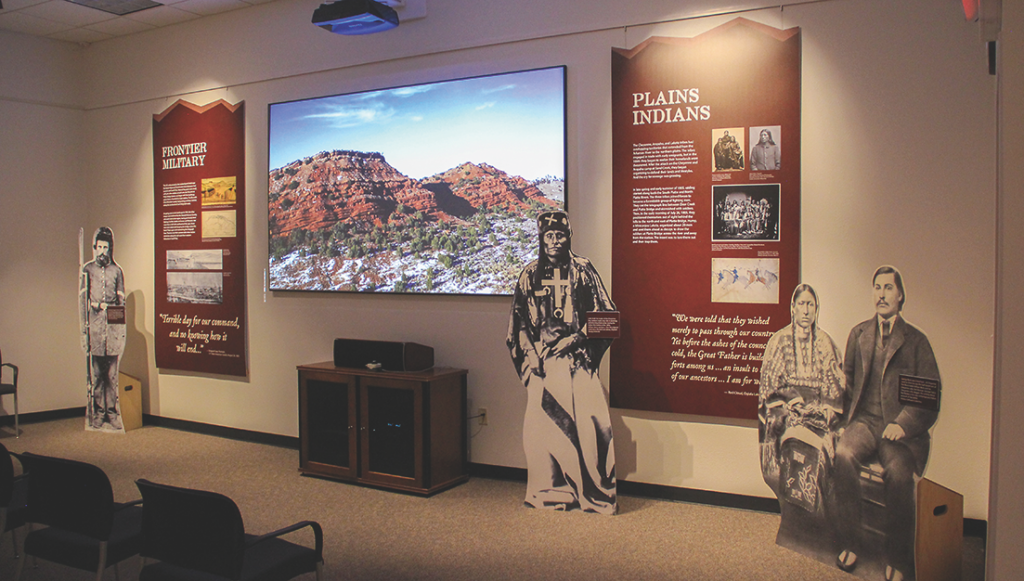

To follow the trail route today, take U.S. 20/26 from Fort Laramie to I-25 and continue to Douglas and Casper. In Casper visit Fort Caspar, where troops involved with the Battle of Platte Bridge and Battle of Red Buttes were stationed. The fort buildings are recreated, and volunteer historians give periodic programs. A new exhibit and film at the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Casper provide detail about the Battle of Red Buttes.

From Casper travel north on I-25. Hoofprints to the Past Museum in Kaycee has information about the Dull Knife Battle, an attack late in the frontier Indian war period in the region. Buffalo’s Jim Gatchell Museum has displays of American Indian accoutrements. North of Buffalo, divert from I-25 to Fort Phil Kearny State Historic Site, a recreation of the fort built to protect the Bozeman Trail, and then follow state highways and county roads to locations where important fighting took place, including the site of the August 2, 1867, Wagon Box Fight and the battleground where the Lakota and Cheyenne warriors surrounded and killed Lt. William J. Fetterman and 80 troops on December 21, 1866. Historians have often referred to this as the Fetterman Massacre, but it was a well-orchestrated battle planned by Hump and others that resulted in the deaths of the soldiers. The Lakotas call it the Battle of the Hundred in Hand.

Big Horn to Bozeman

The Brinton Museum near Big Horn, Wyoming, holds a significant collection of Lakota items from clothing to war weapons, as well as other rare American Indian objects.

After following I-90 from Sheridan north into Montana, cross the Crow Reservation on Highway 91 to Chief Plenty Coup State Park, and then return to I-90 near Laurel and drive west across Bozeman Pass to Bozeman before continuing southwest to Virginia City. Some 1,500 travelers followed the Bozeman Trail in 1864, with more following until 1868, when forts Reno, Phil Kearny and C.F. Smith were abandoned, and a new treaty was negotiated with Oglala leader Red Cloud and others.

The Bozeman Trail had provided a route to Montana’s gold at Alder Gulch, but at a high price with soldiers and civilians killed along the trail, and definite impact to the Indian camps and families. Because the forts were abandoned, and the Bozeman Trail closed, the tribes claimed a victory when the forts were vacated and soon burned.

There are divergent views on the end of the fighting along the Bozeman Trail in Wyoming. Donovin Sprague explains it this way: “I think what the paperwork says is that the military said it’s no longer feasible to maintain these three Forts: Reno, Fort Phil Kearny, Fort C.F. Smith. But what we say is that the Lakota and Cheyenne defeated the United States of America. And so, with that, it’s back like it was. There’s no wagons, there’s no non-Indians.”

The tribes had successfully closed the Bozeman route to Montana’s gold.

A Wide Spot in the Road

Fort C.F. Smith and Chief Plenty Coups

The Bozeman Trail crossed Crow lands north of the Bighorn River, and travelers today can do the same by visiting Fort C.F. Smith and Chief Plenty Coups State Park. During the height of tension along the Bozeman Trail, Lakota and Cheyenne warriors orchestrated regular and sometimes coordinated attacks on sites along the trail. On August 1, 1867, they engaged with soldiers from Fort C.F. Smith in the Hayfield Fight. The Crow Indians did not battle with the soldiers. As traditional enemies of the Lakota people, they became more allied to the soldiers, even though the Bozeman Trail also cut through their lands. Plenty Coups became a chief of the Crow tribe by the time he was 28 years old, and he was recognized for his bravery and leadership, fighting in many ways for his family and tribe.

In 1884 he settled on a farm, which was deeded to him through the Indian Allotment Act. That farm, where he lived until his death at age 84, is now Chief Plenty Coups State Park, located on the Crow Reservation south of Billings. In addition to original farm buildings, remnants of an old apple orchard, and trails across the property, a visitor center has displays of Crow heritage items.

To reach these sites, take I-90 north from Ranchester, Wyoming, and then head west on Highway 91 to St. Xavier, Montana. At St. Xavier, follow Montana 313 to Fort C.F. Smith, and then to Chief Plenty Coups State Park.

Crow Reservation, Pryor, MT Courtesy SoutheastMontana.com

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: Js Bar and Grill, Casper, WY; Montana Brewing Company, Billings, MT; The Coffee Pot, Bozeman, MT;

Wells Fargo Steakhouse, Virginia City, MT

Good Lodging: Occidental Hotel, Buffalo, WY; Fairweather Inn, Virginia City, MT;

Nevada City Hotel and Cabins, Nevada City, MT; C’mon Inn, Bozeman, MT;

Hotel Bozeman, Bozeman, MT;

Just an Experience, Nevada City, MT