A city kid visiting the West eyes a cowboy up and down, then asks him, “Mister, why do you wear a big hat?”

A city kid visiting the West eyes a cowboy up and down, then asks him, “Mister, why do you wear a big hat?”

“My hat protects my head from the sun, the rain, the wind and the cold,” the cowboy replies.

The kid considers that for a moment, then asks, “Why do you wear that vest?”

“Well, my vest has lots of pockets where I can keep things I need handy,” the cowboy explains. “It also frees up my arms to throw a rope.”

The kid points at the cowboy’s chaps, and asks, “What are these funny leather things on your legs?”

“They’re chaps,” replies the cowboy. “They protect my legs from cactus and thorny bushes.”

Then the kid looks at the cowboy’s feet. “I thought cowboys wore boots?” the kid points out. “What’s up with the running shoes you’re wearing?”

“That’s so nobody thinks I’m a trucker,” the cowboy replies.

As suggested by this joke, the unique clothes worn by cowboys and ranch hands help them do their work and protect them from their work environment, which is anywhere cattle can graze. Thanks to dime novels, Wild West shows, movies, Country music and other forms of mass entertainment, the cowboy has attained mythic stature in the American saga. Mixed in with leather-clad mountain men, fearless Indian fighters, daring outlaws and legendary lawmen, the cowboy still represents the Old West.

In addition to his independence, courage and resourcefulness, the cowboy is celebrated for his signature attire. In reality, his clothes were both shaped and limited by his circumstances, the goods available to him and his choice of profession. The 19th-century cowboy’s wardrobe may have been limited—as was his reign of the plains—but he would cut a dashing figure across screens and the imaginations of people around the world.

The American cowboy would become our greatest national hero, and his clothing, America’s only indigenous fashion category: Western wear.

Original Cowpuncher’s Outfit

With some regional and individual differences, an Old West cowboy’s basic getup consisted of tall boots with big-roweled spurs, wool or cotton trousers under leather chaps, a nondescript shirt under a waistcoat or vest, an oversized neckerchief and a wide-brimmed hat. A rain slicker or a duster was often tied to the cantle of his saddle (as well as some form of self-defense, but that’s a whole other topic). Except for the shirt and pants, every piece of a cowboy’s clothing was tailored to the cowboy’s professional needs.

A hodgepodge of cultural and stylistic traditions converged, and frequently clashed, on the Western frontier to create the original cowpuncher’s outfit. The leather shirts, pants and moccasins worn by American Indians were adopted by early European adventurers, including the fabled trappers, mountain men and, later, buffalo hunters. Cowboys had little use for Indian ways; they opted for European uses of leather for boots, belts, gloves and, occasionally, vests and overcoats. Victorian styling was the high fashion of the day, and elements of that buttoned-up ethos naturally influenced the cowboy’s way of dressing—as far as it was practical.

All this was limited, of course, by his financial circumstances. Cowboys have never been particularly well-paid (a pair of boots could cost a month’s salary). Consequently, early cowboys, especially the boys recruited to drive cattle north from Texas, were a motley crew whose wardrobes consisted of one set of clothes each.

With their apparel sometimes proving inadequate to long days in the saddle, American cowboys subsequently bought, or made, clothes designed to meet the needs of their profession. Fancy embellishments on cowboy clothes would come slowly, grounded in practical considerations for structure or durability.

Sombreros to Stetsons

Long before cowpunchers began trailing beeves out of Texas in the 1860s, Hispanic horsemen tended vacas, Spanish for cattle, in Mexican Territory from Tejas to California. Known as “vaqueros,” these mounted herdsmen wore flashy garments: wide-brimmed sombreros, short waistcoats and jackets, colorful serapes, leather chaparreras over short pantaloons and tall-topped boots.

In a fatal decision to populate the area, the Mexican government invited American settlers to immigrate. As Texian cattlemen appropriated Mexican cattle and land, they adopted elements of the vaquero’s working attire. Modern buckaroos throughout the Southwest inherited much of their forebearers’ culture, including their name—an imprecise rendering of the word vaquero.

The dimensions of the sombrero overwhelmed the anglo interlopers who wore small-billed caps, slouch hats, bowlers and derbies. In 1865, Philadelphia hatmaker John B. Stetson designed a more modest version that still sheltered its wearer from the sun and rain. Stetson’s “Boss of the Plains,” originally a hand-felt design meant to amuse traveling companions on a tour of the American West, quickly became the first, and arguably the most distinct, identifiable part of a cowboy’s ensemble.

Cowboy Boots

The cowboy boot came next, leaving an indelible footprint on the Western landscape.

American and European horsemen decamping for the West after the Civil War arrived wearing low-heeled stovepipe boots or military issue cavalry boots and Wellingtons—calf-high boots with a standard shoe heel. Immigrants traveling West by foot or on wagons or in trains wore Wellies, brogans, moccasins or even went barefoot.

None of these footwear options suited cowboys spending 10 to 12 hours at a time in the saddle. Cobblers in Coffeyville, Kansas, are generally credited with producing the first boots that satisfied the needs of drovers trailing herds through the area in the early 1870s. These boots featured round toes, narrow, reinforced arches and higher heels.

The first boots were custom made and handcrafted. They lacked the stitching and other ornamentation commonly seen on modern cowboy boots. Stitching would come about as a way to stiffen the tall leather shafts and keep them from slouching. Another shift in the boot’s design was the high, underslung heel—adapted from the similarly-styled “Cuban heel”—which helped prevent the rider’s foot from slipping through the oversize stirrups on Western saddles. (Some observers contend that the heel made cowboys feel taller and gave them a little swagger when they walked. The reality is probably a little of both.)

In 1879, H.J. “Joe” Justin moved to Spanish Fort, Texas, to make boots for cowboys herding cattle north. Justin and other pioneer bootmakers, such as Tony Lama and Sam Lucchese, soon dominated the cowboy market with their high quality, comfortable boots. Justin was the first firm to offer mail order boots, with a measuring system invented by Joe’s wife Annie. The system revolutionized custom bootmaking, making Justin famous throughout the West as it became settled.

Cowboy boots eventually became palettes for artistically-inclined bootmakers who were happy to oblige the vanities of preening cowpunchers and, later, Hollywood cowboy actors and Nashville musicians. The comfort and fit demanded by Western boot customers in the 1980s would radically change the components and construction of cowboy footwear. Plain Wellingtons, known as “ropers,” became a fad in the 1980s, largely because of their shoe-like fit. In the early 1990s, technologically-advanced boots introduced by a new company, Ariat, revolutionized Western boots and created a whole subcategory of Western and riding boots.

Cotton serge de Nimes

In 1873, Jacob W. Davis, a Latvian-born tailor in Reno, Nevada, asked his fabric supplier in San Francisco, California, to help him with a patent. Davis thought that small copper rivets could reinforce seams and pockets on waist-high overalls he was making for miners. Levi Strauss agreed the rivet design was a potentially profitable innovation, and the pair partnered up to produce these overalls in volume.

They started out making the work pants from hemp sail cloth, eventually turning to cotton serge de Nimes, or denim. By the 1890s Levis were being sold to blue-collar workers of every stripe, as well as marketed to ranchers and cowboys. A couple more decades passed before denim jeans became the signature trousers of cowboys.

By the 1880s, the hats and boots worn by working cowboys had been refined to the point that they would not change appreciably, just stylistically, for the next 100 years. The other gear worn by cowboys, pants and shirts, would be transformed as the mythology of the West and its most famous inhabitants took on a life of its own.

The Wild West Show & Rodeo Look

In the last decades of the 19th century, the exploits and stories of adventurers, Indian fighters, outlaws, lawmen and cowboys were related in the vivid, often lurid prose of dime novels and magazines gobbled up by city folks enthralled and terrorized by life on the frontier. The popularity of the writings, which were often a mixture of fact and fiction, initially spawned small theatrical productions depicting vignettes of frontier dramas and re-enactments of popular events. Real-life characters straight out of the pulps and fresh from the West, including the likes of William F. Cody, “Texas Jack” Omohundro and James Butler Hickok, were recruited to portray themselves. The success of the theater events inspired the idea of grandly-staged Wild West exhibitions featuring all the denizens of the West, including their horses and their apparel.

The fringed leather shirts and coats worn in these shows by Indian fighters and cavalry scouts like Buffalo Bill became associated, and ultimately intermixed, with cowboy clothes. Elements of the Wild West shows would be incorporated in rodeos, which were fast becoming popular attractions in cities back East. By the 1920s the influx of competing cowboys and cowgirls following rodeo money to New York, Boston and other major cities would prove to be serendipitous to a few tailors and seamstresses who repaired or made clothes for rodeo stars. Some of these tailors would have pivotal roles in the future impact and design of Western wear. Indeed, they opened the door for, and inspired, boutique designers of cowboy- and Indian-influenced apparel for men and women. Cowboy couture from designers like Patricia Wolf, Pat Dahnke Designs and Double D Ranchwear found a market for their limited-edition creations in the 1980s that still flourishes today.

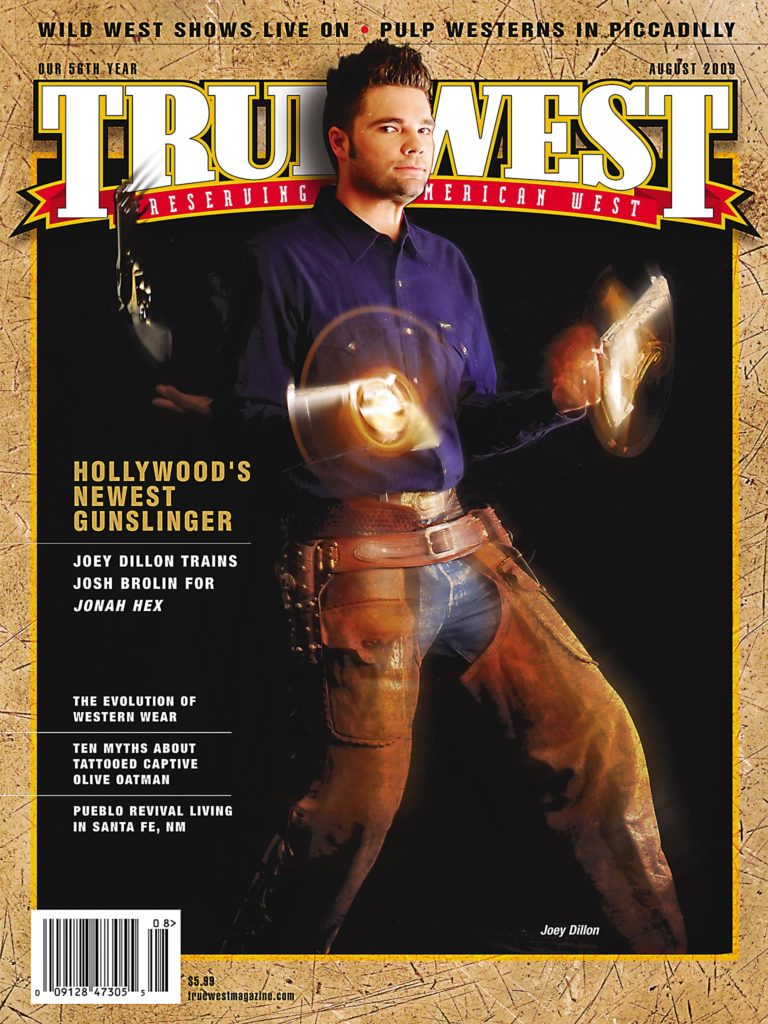

Reel Cowboy Style

The Wild West shows set the stage for the ultimate cowboy myth-making venue, motion pictures. One of the first narrative movies was also the first Western. The Great Train Robbery, a silent black-and-white film produced in 1903, ran 12 minutes and depicted outlaws in realistic cowboy garb robbing a train. One of the actors in Robbery went on to become the first cowboy movie star, “Broncho Billy” Anderson. Broncho Billy, William S. Hart and other early silent movie stars strove for authenticity in their portrayals of cowboys.

While the first Westerns were fairly realistic as far as wardrobes were concerned, movies and their stars soon became more fanciful in their depiction of life on the range. Tom Mix, a former Wild West performer and rodeo champion, was known for his flamboyant personal style before his film debut in 1910. His rugged good looks and penchant for flashy cowboy clothes made him one of Hollywood’s first superstars, and his films set the standard for cowboy movies for years.

The arrival of sound in movies in the late 1920s heralded the rise of the next generation of cowboy stars, including singing cowboys Tex Ritter, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. Around this time beadwork, porcupine quills and other Indian-inspired designs on many cowboy performers’ clothes were being interpreted in colorful overlays and embroidery. Los Angeles-based tailors originally from Eastern Europe, including Nathan Turk and Nudie, were making ostentatious cowboy and equestrian clothes for Hollywood clients. Elaborate embroidery, contrasting piping, smile pockets and cowboy motifs, including steer heads, cactus plants and guitars, became the norm for singing cowboys. When Nashville-based Country music artists began copying the vocal and sartorial stylings of singing cowboys in the 1950s, the musicians upped the ante for garishness by adding sequins and rhinestones to the mix.

Working Cowboys Perfect Western Wear

Not so surprisingly, working cowboys took a far subtler route as their apparel evolved. By the 1920s denim jeans had become the norm. Around that time period an enterprising cowboy sewed a bandanna to the shoulders of his shirt, and the Western yoke was born.

Perhaps the biggest boost to Western apparel as a category was the rise of dude ranches in the 1920s-30s. City dwellers flocked to the West to get a taste of the cowboy life they read about in Zane Grey novels or saw on movie screens. They wanted the whole experience, so they bought Stetson hats and Justin boots and Levi jeans to wear. The modern Western shirt was yet to be developed, but regional shirt makers benefitted from the dudes’ penchant to emulate a “real” cowboy.

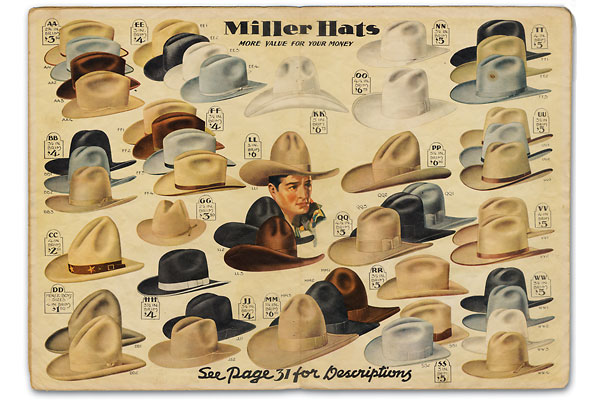

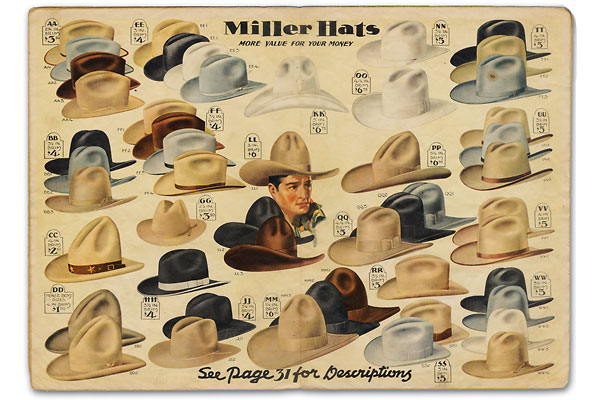

Denver-based Miller & Co. became the first supplier of Western wear to ranchers, cowboys and farmers in the 1920s. Miller’s Stockman stores and catalogs supplied Western wear to countless millions before they were sold off and shut down in the late 1990s. Miller International’s best known subsidiary is the Rocky Mountain Clothing Company. A new Miller Ranch label will debut this fall.

Pendleton Woolen Mills of Oregon produced one of the first shirts identified as a Western-style shirt in the late 1930s. The Western Gambler featured slanted pocket flaps and shank buttons.

The end of WorldWarII saw the rise of the unheralded Western shirt industry. Independently and almost simultaneously, Rockmount Ranch Wear, Karman Western Wear, H-Bar-C/California Ranchwear and Panhandle Slim began pumping Western shirts into the market.

The 1940s-50s became known as a Golden Age of Western shirts, based not only on the popularity of the new style, but also on the sheer artistry and construction that went into many of the production shirts. Snaps and yokes would remain stylish signatures of Western shirts, but embroidery and fancy pocket treatments all but disappeared until the 1980 movie Urban Cowboy revived interest in elaborate details. By the early 2000s, retro-Western shirts from Rockmount Ranch Wear, Scully, Roper, Panhandle Slim and other companies—including a number of mainstream shirtmakers—revived the interest in smile pockets and embroidery that is still a classic style today.

At the same time, Wrangler’s 13MWZ jeans appeared with its innovative zipper and repositioned back pockets. The modern cowboy’s outfit and the category of Western wear were officially established.

The 1980s also saw the return of Victorian-era cowboy apparel. The 1989 mini-series Lonesome Dove turned the frock coats, bib shirts and vests that were popular among re-enactors into a mainstream look. A number of Western manufacturers continue to make Old West-styled shirts, but a few, including the Old Frontier Clothing Co. and WahMaker by Scully, specialize in the look.

As times, tastes and technology change, so do the cowboy’s clothes. Sleekly smooth Shantung straw hats made from paper fiber and woven in China would be introduced in the 1970s by Resistol, while factory-distressed straws from Shady Brady and Dorfman Pacific would be hot in the new century. Hi-tech plastics compete with hand-pegged leather for the soles of boot wearers today. But even after 150 years, Western apparel is as distinctive and evocative of the cowboy, and all he represents, as it ever was.