“No matter how a man alone ain’t got no bloody f****** chance.”

—Harry Morgan, To Have and Have Not (1937)

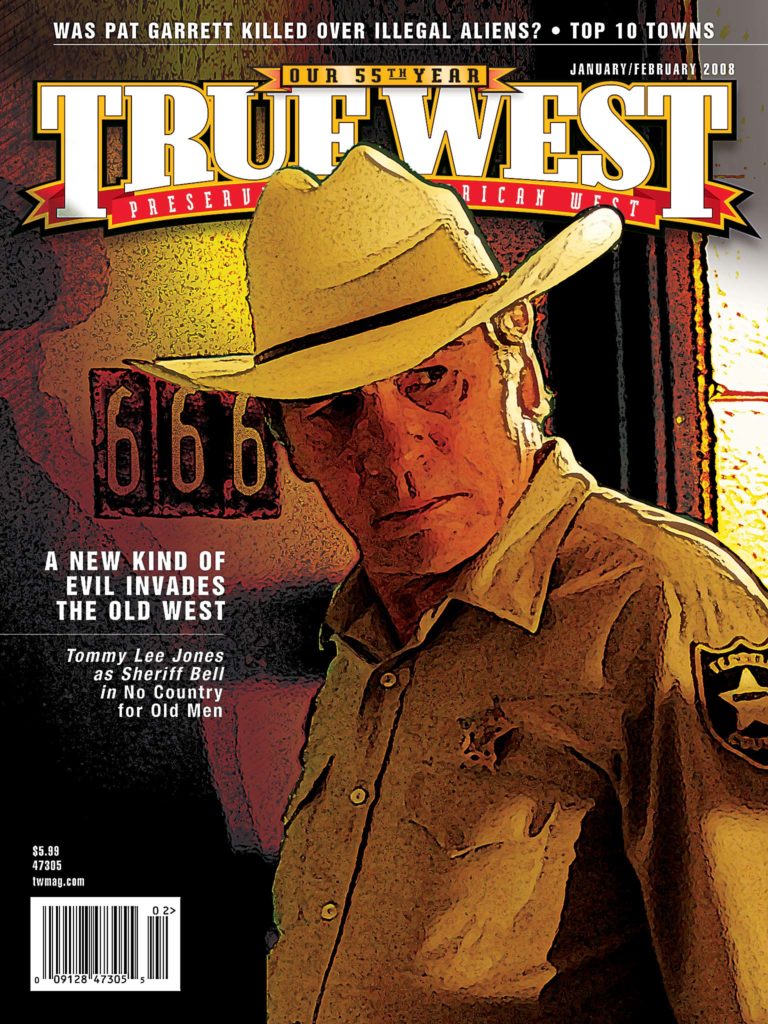

No Country for Old Men is really two movies, especially for audiences who believe they may be coming to see a Coen Brothers picture along the lines of earlier crime-driven works by Joel and Ethan, such as Blood Simple (1984), Miller’s Crossing (1990) and Fargo (1996). These are pictures that managed to be smart, funny and horrific, all at the same time, and No Country, for the most part, fits well into that group.

The novel by Cormac McCarthy would seem to be an almost perfect fit. Set in 1980, it’s the story of a resourceful, somewhat haunted Vietnam vet, Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), who happens upon a crime scene while hunting.

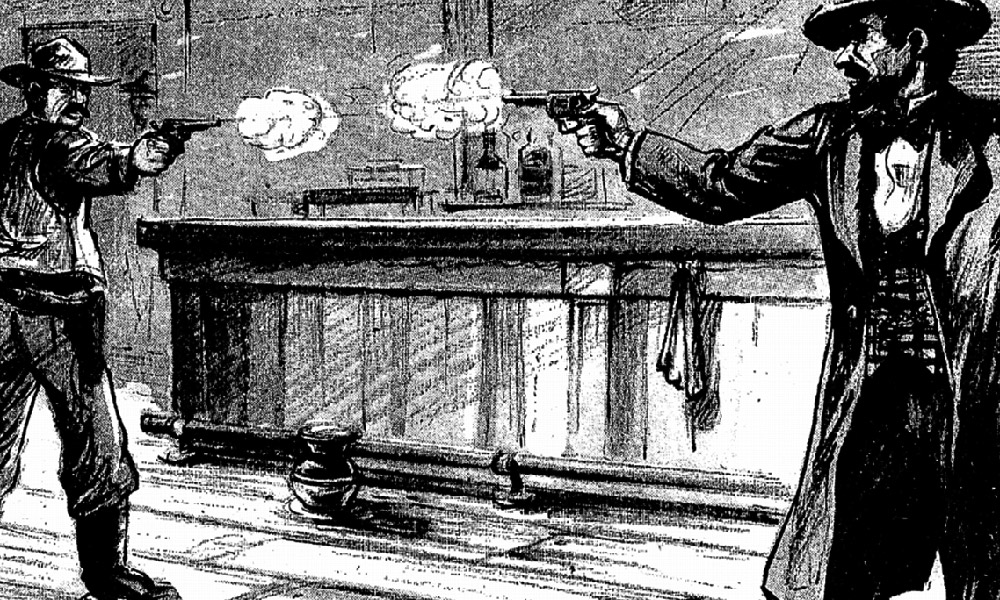

Spread out over a half acre of dirt in a gully in West Texas are the bodies of a group of men, their vehicles and a dog or two, all dead or dying. Still sitting on the back of one of the pickup trucks are the stacks of packaged heroin bricks, and not far from the site, beneath a tree, is the dead man who dragged himself away with two million in cash in a case.

When Moss decides to remove the case, he sets in motion the machinery of the plot which primarily involves his pursuit by merciless, relentless killer Anton Chigurh (pronounced Sugar, played by Javier Bardem)—the Pepé Le Pew of psycho killers who sports a Peter Tork haircut.

Chigurh enjoys his work to the extent that his weapon of first choice is a pneumatic retractable-bolt device of the sort that was once used to stun cattle. That it means Chigurh has to carry a tank of compressed air wherever he goes doesn’t seem to bother him in the least. What’s more, the device works equally well at killing and punching out cylinder locks in stubborn motel doors.

Not far behind is the local sheriff, Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), who has seen a good deal in his time, but when this deal is wrapped up, he will have likely seen it all, or as much as he’s willing to bear. Also on Moss’ trail are a few others who would like to retrieve the money, including a former colonel, Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson), who is working for the bad guys.

It takes a while before Moss realizes he’s carrying a tiny transmitter. Then staying alive becomes a 24-7 job, as he runs all over the Texas-Mexico landscape. Elements of Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway (1972) can be seen in the movie, but deeper to the story’s heart and the Moss character is the luckless Harry Morgan from Ernest Hemingway’s existential 1937 crime novel To Have and Have Not.

Jones, Brolin and Bardem are the center of the film, and their performances are flawless. Equally solid is Kelly MacDonald as Moss’ wife Carla Jean and Garret Dillahunt as Bell’s deputy, Wendell.

The Coens and McCarthy make a perfect team, and it’s truly remarkable that the film is so true to the book—that’s the good news and the bad news, and the bad news is not so very bad.

It just happens that while the movie delivers all of the wry and nasty elements one wants from a Coen Brothers picture, close to the end of the story, it becomes clear that in remaining true to McCarthy’s literary vision, the film has to refuse to take any easy outs. The audience is required to step from the Coens’ world into McCarthy’s, and it’s not a gentle or particularly gratifying passage.

The best news is that No Country for Old Men is both an entertainment and a solid, faithful adaptation of a literary work by one of our greatest living writers.

As this story goes to press, No Country for Old Men has just received the National Board of Review Awards for best picture, best ensemble cast and best adapted screenplay (Joel and Ethan Coen, based on Cormac McCarthy’s novel of the same name). It is also winning top honors among the Boston, Washington D.C. and New York critics. The Coen Brothers as directors and screenwriters, and Javier Bardem as the unstoppable murderous golem named Chigurh, are all being recognized.

By the time you read this, the awards season will be in full throw, and it’s reasonably certain that the film will at least see Oscar and Golden Globe nominations in several key categories. [Update: No Country received eight Oscar nominations and won two Golden Globes: Best Screenplay and Best Actor in a Supporting Role for Javier Bardem.]

Bardem is being singled out, but Josh Brolin, Woody Harrelson and Tommy Lee Jones are all outstanding as isolated figures who circle each other in the story but rarely interact face to face, which makes it entertaining that they’re being regarded as an ensemble cast.

As Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, Tommy Lee Jones is a sort of fixed point in the midst of all the carnage and chaos. In our interview, Jones tell us his character represents Good, in the symbolic scheme of things. But with Bell’s impassivity at the heart of the film, he seems to stand for what John Wayne’s character Ethan Edwards referred to as “the turnin’ of the earth.”

I spoke with Jones by phone from his offices in San Antonio, Texas.

True West: Bob Boze Bell, our executive editor, told me the other day he’d just gotten the DVD of Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada.

Tommy Lee Jones: Okay.

I told him he ought to listen to the commentary, you and Dwight [Yoakam]—

Uh huh.

So he did, and he put a number of quotes from it on his True West blog.

Okay.

I don’t know that many people see it as a comedy, but—

Ohhh! Good for you, to mention that word, comedy. Of course that’s the foundation and the spine of the movie, yes.

The line that I liked from the disc, Dwight Yoakam says, “Human behavior is so ridiculous and absurd at times,” and you answered, “Otherwise, Dwight, there would be no divinity.”

Oh, no, I don’t remember having said that, but it sounds like it makes sense. Yeahhh. I’d forgotten about that. Dwight and I did that. I’d forgotten.

And the girl was there too, but not much.

Oh January [Jones]. She’s not an overly loquacious girl.

Not much room between you and Dwight.

Dwight’s awfully good company.

Are you a fan of Cormac McCarthy?

Well, I’ve read all of his books and I’ve read most of the criticism that’s written about them—I don’t think if you take literature seriously, fan is not quite the right word, but yeah I like his work a great deal.

How did you get approached for the part?

Well, they sent me a script and asked me if I wanted to play Ed Tom Bell, and I read the script and I said yes. It was that simple…. I think Cormac is our best living prose stylist.

No Country is unique, though. It’s less dense than his other novels.

You couldn’t say that Blood Meridian is an easy book. But he’s not a simple man. He doesn’t have a simple mind, and he’s a truly great writer, and capable of just about any style. He’s entirely original every time he goes to work.

There’s some discussion as to whether No Country and Three Burials are really Westerns, since they’re contemporary.

Well, I don’t have anything to say about Westerns because I don’t know what they are. I assume it’s kind of a generic term to indicate a movie that’s got big hats and horses—and maybe some dust in it.

And I’ve never been able to really think about motion pictures in terms of genre, you know. You can talk about Romantic Comedies and Musicals and Situation Comedies and try to come up with some way to use the word genre as it applies to motion pictures, and the best you’ll ever do in that endeavor is demonstrate a firm grasp of the obvious. So I don’t really have anything to say about the Western because I’m interested in making good movies about the life and times of my own and that inevitably is gonna involve big hats and horses, but I don’t have anything thematic to say about the so-called Western. I don’t think life, and I don’t think cinema, is that simple.

I think this movie is a very good one made by some very good filmmakers, Ethan and Joel Coen, and Javier Bardem and Kelly MacDonald and Josh Brolin and Roger Deakins, the cinematographer, I think it’s the third time I’ve worked with him, he’s a good friend and from my point of view a highly admired coworker.

The thing I appreciated most about Joel and Ethan is their respect for Cormac’s book and how closely they adhered to it, and the fact that they had the wisdom to not presume to improve it.

That’s rare.

Yeah.

Deakins was also the cinematographer for 2007’s Jesse James movie.

I know.

Which is likewise faithful to Ron Hansen’s book.

Didn’t read it.

I have to say that when I talk with many Western buffs, the definition of what a Western is and isn’t can be something of an issue.

Don’t you get bored with that?

Sometimes, but I don’t much mind studying on it. After all, there are some who put Star Wars in the genre and others who get off the train at Hopalong Cassidy.

Oh, I loved Hopalong Cassidy when I was a kid! One of the proudest days of my life was when … my dad took me to town and it was in Rotan, Texas, a very small town, and we went into a store and [he] asked if there was anything I wanted. And there was a little sleeveless sweater that was woven, and it had Hopalong Cassidy on the front of it. And it was one of the proudest days of my life that my dad decided to buy me a Hopalong Cassidy sweater.

When I was a little kid, I thought Hopalong Cassidy was a hero. And he was.

He was.

And still is.

And that was all William Boyd. He made that happen. He was very shrewd.

I can’t imagine anybody doing a remake of Hopalong Cassidy because the audience is no longer there.

There are those who still see Hopalong Cassidy and Gene Autry as the template for what they feel Westerns ought to still be.

The fact is, life is not like that. It’s even less like that today than it was then.

Was it ever like that?

No.

Maybe for some people who had come out of the war, a Depression, those pictures made things easier to bear.

Yeah. Sure enough.

I was talking to Garret Dillahunt—[who plays Deputy Wendell in the film].

What a good young actor! A good young man too.

He was telling me that Javier Bardem was asked to have an accent for the part of Chigurh, and that the accent couldn’t be Spanish. Since Bardem is from Spain and doesn’t speak much English, it was daunting for him.

I don’t know how tough it was. You can’t tell if anything’s tough for Javier because he makes everything [look] easy. He wound up with some kind of accent—he could have been a Spaniard or a Serb. What the part called for was some kind of nondescript slight foreign accent. I think his work is impeccable and he did just the right thing with the accent. And I don’t think that Javier would be inclined to speak to degrees of difficulty. But I can’t imagine Javier being intimidated by anything.

Chigurh is an uncommon character; he seems to be almost mythical in the book and in the film, a kind of force of nature, or a representation of something—

I suppose you could say that his character represents evil, the character of Ed Tom Bell represents good and the character of Llewellyn Moss represents the common man caught in the struggle between the two. And you could go on and wax loquacious about the construct of the metaphor at work here, and again, you would have a firm grasp of the obvious.

What you ought to be thinking about is, how do you make a big metaphor like that work? You do it through being specific and believable and utterly inarguable in the reality of the narrative. And that’s where Cormac is so good, and the Coen Brothers are so wise in following his lead.

Hang on one second—

[Off phone] Y’all goin home? We’ll see you tomorrow. Okay. Good night.

We’re closing up shop here this evening.

So what distinguishes the metaphor from flesh is the honesty of it; you don’t want to see a movie with metaphors, do you?

No, but if you do, you want them well disguised as entertainment.

Or something.

Or something. Something original.

Metaphors have to have some blood pumping in them.

Yes they do. And some ground to stand on.

Otherwise there’d be no divinity.

Ha ha. That makes a lot of sense.

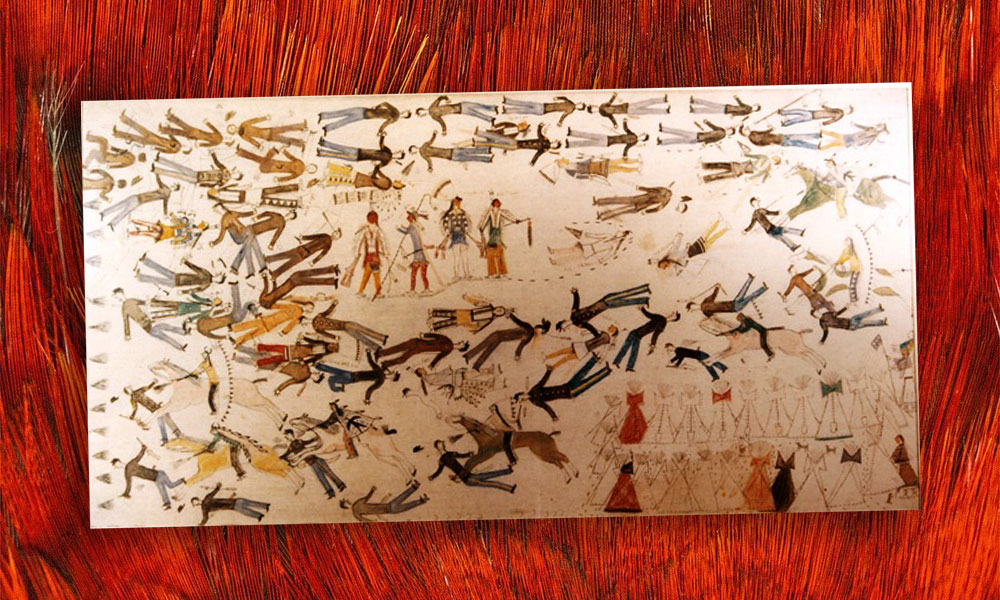

COMANCHE MOON

With Comanche Moon, the saga of Lonesome Dove comes to its final conclusion, as both a novel (1997) and a six-hour CBS movie airing on January 13, 15 and 16.

Even though Larry McMurtry’s book and the new miniseries bid farewell to that ragged bunch of Texans who first appeared in print in 1985, the events in Comanche Moon actually take place prior to the first Lonesome Dove TV series that aired in 1989. In other words, it’s the sequel to prequels and a prequel to … um, maybe it’s better to not go down that road.

Suffice it to say that those who have been missing the spunky Gus McCrae and dour Woodrow Call, Call’s bastard Newt, the hapless Jake Spoon and long-suffering Maggie, and the usual passel of Texas Rangers, Austin civilians and murderous Comanches, should take some comfort in knowing that they have returned from TV limbo to visit once again.

Making their first appearances on your big screen TV are a new villain, the evil Mexican Ahumado (Sal Lopez), whom even the Comanches fear, and the odd and urbane Ranger commander Inish Scull (Val Kilmer), who spends some time as the prisoner of Ahumado in a cage high up a cliff and then later in a snake pit.

Scull also has a wife, Inez (Rachel Griffiths), who is given to bedding just about any hapless male who piques her interest, or even wanders into view, particularly while her husband is away, which appears to be as often as he can manage. Her drives are, as Michaleen Flynn might have put it, “Homeric.”

Steve Zahn does a more than passable approximation of Robert Duvall as McCrae, much as David Arquette did before him in Dead Man’s Walk (1996), and Karl Urban handles Call with a scowl that would do Seth Bullock proud. It will be curious to see how he portrays the young Dr. McCoy in the upcoming Star Trek film.

Back for this grand curtain call is the original Lonesome Dove director Simon Wincer, as well as writers McMurtry and his collaborator Diana Ossana.

It would seem as though the miniseries has everything it needs to be a howling success, especially if one is acquainted with the novel, which is wicked and brilliant.

Unfortunately, this is not the case.

For example, the same traits that make the novel’s Inish Scull fascinating have, on the screen, curdled him into mere eccentricity; he’s become a Western variation on the stalwart Victorian adventurer, minus the pith helmet. When we meet him again, late in the story it looks as though Kilmer is doing a bad sketch parody of Mark Twain (weirdly, he’s starting to resemble 1940’s actor Howard Da Silva).

His wife Inez has had all the fun and farce sucked out of her. If ever a character cried out for the full no-holds-barred cable treatment, it’s Inez Scull. As written, she deserves a miniseries of her own and then some (how about it, Mr. McMurtry, Inez Does Cuba?).

As for the regulars, sadly, McCrae and Call are missing their warmth, the quality that bonded them in the earlier ventures. Without that chemistry, the story is all foreshadowing; it’s about what they were and will be, and most of the excitement we look for has to come from our familiarity with the earlier films and books.

McMurtry filled his novel with fine, smart twists and terrific bits; his Comanche Moon is often grisly, but it’s also a hoot. This series is neither. The sweaty humanity of Lonesome Dove has been lost to sweeping vistas and big music, and the picture chugs along making a point at a time, like chapter headings.

The sin of Comanche Moon, and it’s difficult to see where to place the blame since all the major players you could hope for are in play here, is that it’s an adult adventure trapped in the body of an all-ages, family-friendly Western. Wholesome entertainment has its place, but McMurtry’s novel is high proof, not sarsaparilla, and it deserves to be within reach.