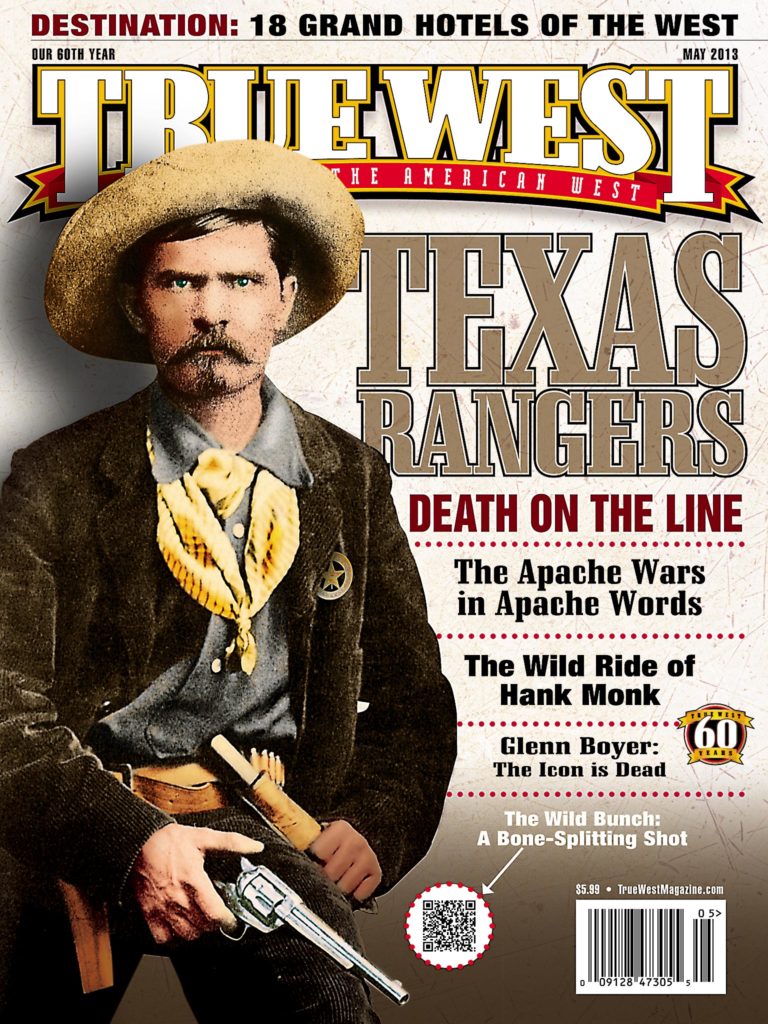

The Icon is dead. Hear the sounds of sadness, relief and … conflict.

The Icon is dead. Hear the sounds of sadness, relief and … conflict.

Glenn G. Boyer was the Icon, a nickname given to him by one of his admiring fans. For a number of years, the nickname was close to true; Boyer was the acknowledged expert on Wyatt Earp and company…until the walls came tumbling down.

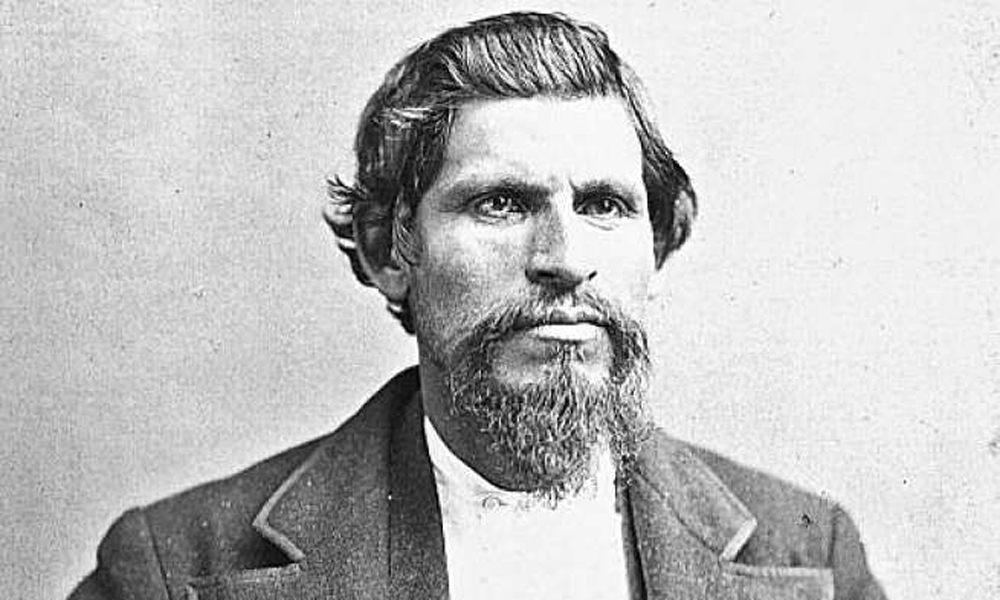

Boyer had first developed an intense interest in Wyatt and Tombstone when he was assigned to an Arizona base after joining the military in 1943. After his 1965 discharge, he befriended Wyatt’s niece, Estelle Miller, and other Earp kin. Miller apparently gave Boyer family documents and memorabilia, a treasure trove he often promised to show researchers such as Gary Roberts and Casey Tefertiller, only to produce nothing when they visited him (his supporters claim they got to see Boyer’s materials).

By 1967, he utilized the Earp kin material to write his first book in a trilogy, The Suppressed Murder of Wyatt Earp, which was actually about how other writers had “murdered” the factual details of Wyatt’s life and personality. Later came Wyatt Earp’s Tombstone Vendetta and the blockbuster I Married Wyatt Earp, purported to be the remembrances of Wyatt’s third wife, Josie Marcus. It became the second all-time best-selling Earp book, after Stuart N. Lake’s seminal 1931 Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal.

The Icon was riding high. But historians began pointing out discrepancies, provable errors and unlikely dialogue in his work, especially in I Married Wyatt Earp. That book allegedly shares Josie’s conversations with Wyatt and Doc Holliday, despite the fact that she had refused to talk about that time of her life with even her close relatives and friends.

In the 1990s, a group of Old West historians tore Boyer’s writings apart with critical analysis. The Icon responded—usually by questioning his accusers’ sexual preferences or dismissing them with colorful language. Up until his death, he surfed Old West message boards, posting comments that impugned the motives and characters of the nonbelievers.

The Icon, you see, was cantankerous, caustic, profane and egotistical. He believed the best defense was a good offense. He frequently threatened his enemies with lawsuits, although he never did sue anyone. Sometimes he intimated physical violence against his accusers.

He could also be charming and disarming, which helped him cultivate a posse of friends and followers who stood by Boyer and even attacked those who dared to question him or his work.

By the late 1990s, with a preponderance of evidence against him, Boyer changed his tune. He claimed he had always written creative nonfiction. What did he think about those who had believed in his Earp trilogy—or, even worse, had used his material in their own books or movies or TV shows? He sneered that they were suckers who should have conducted their own research.

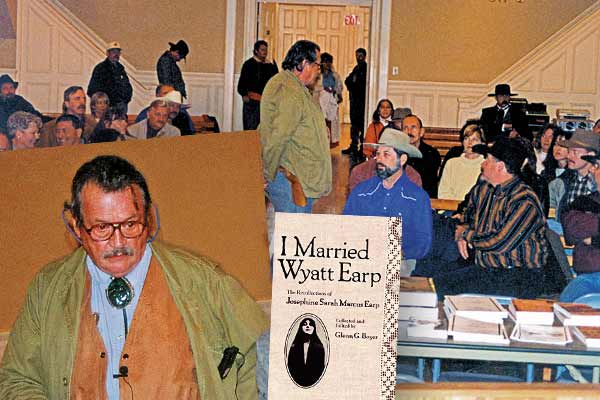

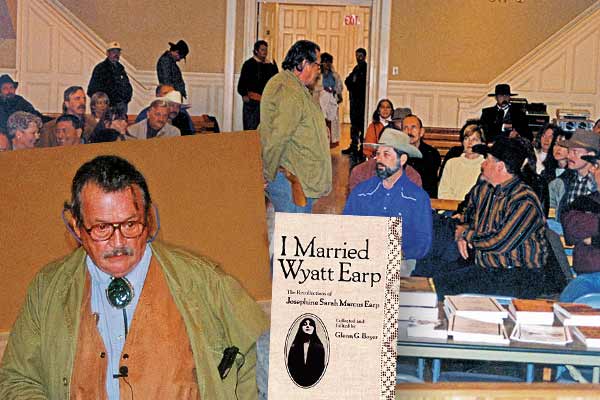

The climax came, appropriately, in Tombstone. On November 4, 2000, the Icon was signing books at Schieffelin Hall when Inventing Wyatt Earp author Allen Barra, a particularly strong critic of Boyer’s, walked into the hall with his family. Boyer and a few others immediately got into Barra’s face, yelling and threatening. Adding to the tension: the Icon and his stepson Danny Coleman were both armed with pistols. Several people feared violence might erupt, but thankfully everyone cooled down.

Not long after, Boyer decided to focus strictly on writing fiction.

Boyer died in Tucson, at 89, on Valentine’s Day, an ironic date for a man unloved by so many Earp experts. Even dead, he will likely remain a lightning rod for years to come. He would have had it no other way. He loved the fight; he relished the attention.

For he was, and is, the Icon.