For almost 80 years, archaeologists were pretty sure how and when the first humans came to the New World.

A 1932 excavation of a prehistoric village near Clovis, New Mexico, established that people first showed up in North America at the end of the last Ice Age, around 13,000 years ago. They came across an ice bridge that spanned the Bering Strait. Those first people are known to science as the “Clovis Culture,” and most accept them as the ancestors of all native people.

So it caused quite a stir in April 2008 when Oregon archaeologists announced they had scientific proof people were here at least 1,000 years earlier, before the ice bridge formed.

The revelation means everyone has to rethink almost everything we know about ancient people.

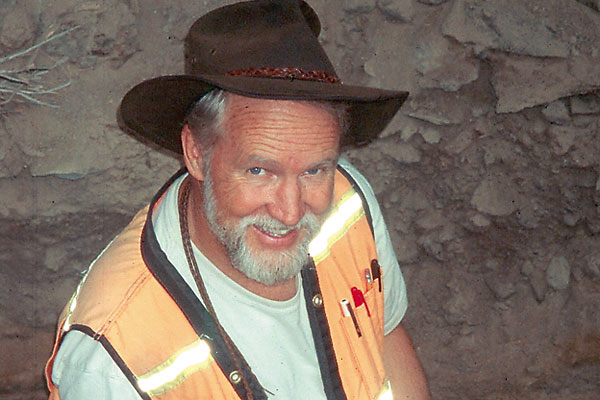

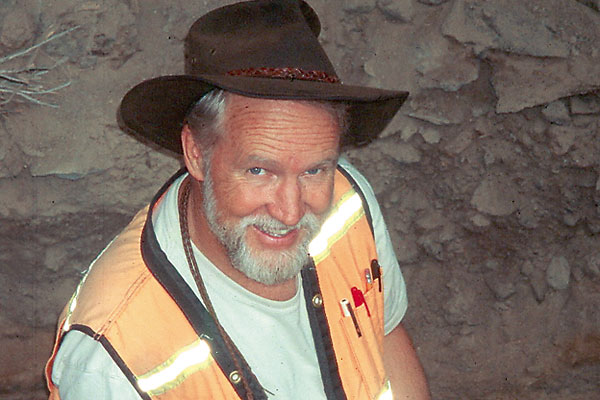

Dr. Dennis Jenkins led the team that made those remarkable discoveries right in his own backyard in south-central Oregon. “Native Americans love it, they say, ‘Dennis, I’ve told you we’ve been here forever.’”

The search began in 1989, when Dr. Jenkins began teaching at the University of Oregon Field School. He and an associate developed a research plan to investigate the seven Paisley Caves in Oregon where ancient remains had been found in the 1940s. The human and animal bones were suspect because scientists worried they had been “mixed” over the centuries, so they wouldn’t accept them as proof that the bones pre-dated Clovis Culture.

In 2002, focusing on Cave Three, Dr. Jenkins decided to test again to see if the earlier theories were correct. “Grave robbers had seriously disturbed the cave, and that was daunting, but it didn’t stop us,” he says. “We found camel and horse bones, a few threads and some human coprolites [fossilized feces].” The waste material is like gold, he explains, “Once it is dried, it doesn’t change, and this was entirely dried up like a mummy.”

From such waste archaeologists can establish age and what was eaten and most important, they can extract DNA, the building block of all life.

The waste was sent to Copenhagen, Denmark, to be studied: Did it contain ancient DNA, was that DNA native (all native people share two specific markers) and just how old was it?

Dr. Jenkins remembers being at his lab in a WWII quonset hut at the University when he got an e-mail that would change his life: “How old do you think these coprolites could be?” a playful scientist from Copenhagen asked. Jenkins excitedly e-mailed back “Why, what did you find?” He got back the answer, “We’re getting ancient native DNA out of them.”

Dr. Jenkins wanted to jump up, pump the air and shout, yet he was cautious. “This was exciting, but way too many times, people thought they found pre-Clovis material and later it was shown they were just wrong.”

Two more years passed before the European scientists finished all their tests and ruled out any other possibility. For instance, they had to establish none of the Oregon scientists or students were natives who could have handled the material and thereby contaminated it.

When all the tests were done, proving these were native remains from as long as 14,300 years ago, that is when Jenkins jumped in the air, pumped his fists and shouted in triumph.

“These were the most extensive genetic tests I know of,” he says, and they established without a doubt that the Clovis Culture was a Johnny-come-lately. The new oldest ancestors are now the Paisley Culture.

“We have to now question how people got here,” he notes, “because they couldn’t have walked over the ice bridge because it hadn’t opened up yet. They had to get here another way.”

Did they come down the Pacific Coast by land or boat? Or were they here before the ice bridge formed? Or maybe they didn’t come from the north at all; maybe they came from the south. And maybe the Paisley Culture isn’t the oldest culture we’ll ever find. Maybe even older ancestors are out there still waiting to be found. Dr. Jenkins says questions like these thrill his soul.

“This gives us a brand new sense of stimulation—we’ve gotten past the Clovis barrier,” he says. “And Native Americans love it that we can study their ancestors [through the coprolites] without disturbing bones. It has really opened many possibilities for other archaeologists.”

These first inhabitants ate bison and small animals, consumed prickly pear and rose hips, and drank a lot of water. “But we have no clue what they looked like,” Dr. Jenkins says.

In December, the High Desert Museum presented him with its 26th Earle A. Chiles Award, in honor of this “milestone in archaeology.” Dr. Jenkins will lecture on his discovery at the Museum in Bend, Oregon, on May 8.

Dr. Jenkins hopes his discovery will inspire young people to become archaeologists. “I knew I wanted to be an archaeologist since I was 13, after I found a few arrow points. To young boys and girls who are motivated to this field, I say ‘Go for it!’”