On August 27, 1871, an arcing ax handle landed solidly on John Lemon’s head, plummeting him to the ground.

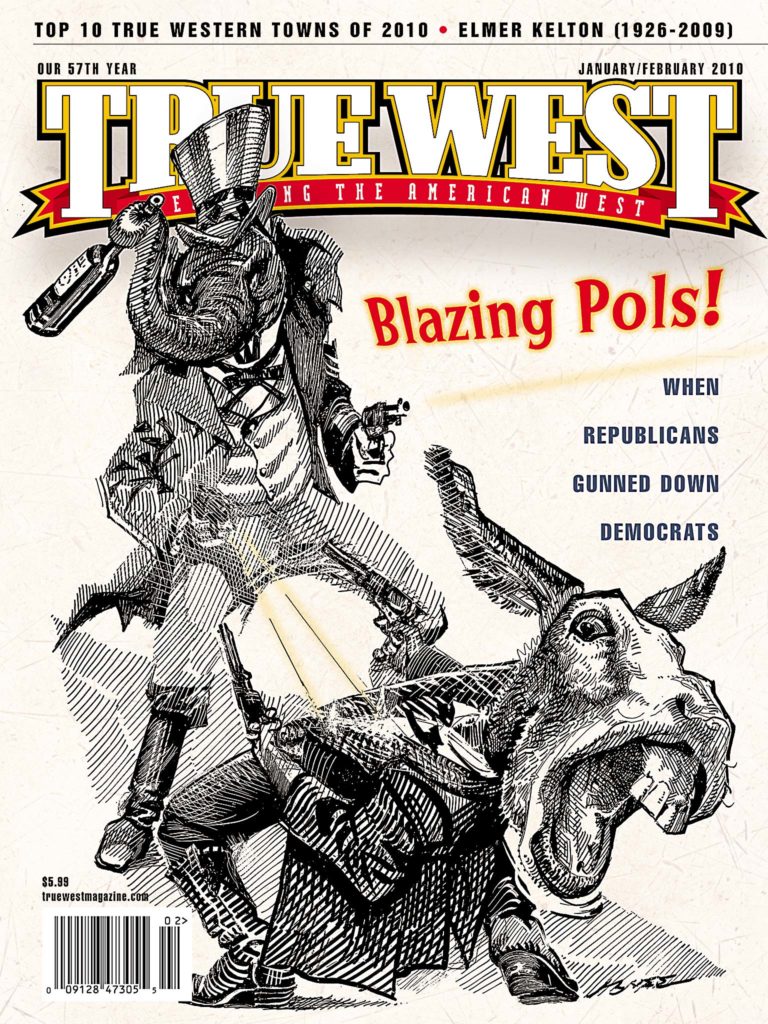

The Doña Ana County politician and Republican party boss—a hopelessly intractable firebrand if one were a Democrat—lay unconscious in the street, wholly oblivious to the pandemonium. On the typically quiet, quaint plaza in La Mesilla, New Mexico, chaos was contagious; gunfire was ubiquitous. Democrats and Republicans were at war!

The upcoming election on September 4 had evoked fanaticism. Partisan control of the entire Mesilla Valley was up for grabs. The Rio Grande ran through this agricultural mecca, making the district fertile and fruitful and financially worthwhile. Republicans and Democrats were vying for political dominance with fervor—each salting campaign rhetoric with fiery words, free whiskey and earsplitting refrains from competing brass bands.

The afternoon sun, scorching, beat down. The blood-alcohol content, numbing, went up. Wooziness claimed its share. Rival musicians marched to loudly hammered melodies around La Mesilla’s plaza—Republicans clockwise, Democrats counterclockwise. With a purposeful in-your-face attitude, the Democratic band piped out a rendition of “Marching Through Georgia,” barefaced skullduggery to dyed-in-the-wool Republicans, many who were former Unionists during a not-too-distant Civil War.

Some 1,000 sweltering participants, wannabe officeholders and curious onlookers filled the town square. Trumpets blasted. Tambourines clanged. Ceaseless drumbeats scored the cadence. Inflammatory taunting and boasting escalated—to a fervently dangerous pitch. Raw nerves frayed.

Proximity was perilous. All felt 10 feet tall, but none were bulletproof. A six-shooter came out. Apolonio Barela’s shot into the air may or may not have been a signal, but the booming report fired both bleating bands into opposing noisiness, surging boiling tempers past the breakwaters of good sense.

Lemon stridently confronted I.N. Kelley, a Democratic activist, declaring he would just as soon shoot him as the next man. That’s when Kelley’s ax handle united with Lemon’s cranium, according to the Democratic version. Republicans asserted the head thumping was unprovoked. Either way, when hard wood connected with the hardheaded politico, the shooting began—at people.

Felicito Arroyas y Lueras shot Kelley five or six times—fatally—before he, too, caught bullets, crumpling him to the dirt street DOA. Additional rioters hotfooted for rooftops, trying to gain high ground and a clear killing field. Others stood toe-to-toe, unleashing hellfire at close quarter. Unarmed men ran home to get their guns. Terrified women grabbed crying children by the hand, dashing for safety. Innocents were caught in the middle. One, a mentally retarded boy, was killed outright.

Republicans were indiscriminately shooting at Democrats; Democrats were haphazardly shooting at Republicans. Bleary-eyed drunks were just shooting—wildly. La Mesilla’s tightly confined plaza was a war zone. The list of casualties—dead and dying—was climbing. Inside 15 minutes, upwards of 500 shots were fired. The wounded, who could count?

Someone, exhibiting good judgment, dispatched a courier to Fort Selden some 20 odd miles upriver. Surely, Uncle Sam’s cavalrymen would put a kibosh on the senseless slaughter underway.

As an evening sun set and night breezes swept away dissipating wisps of burnt powder, the crowd cautiously dispersed—those who were mobile. Others screamed for help—or mercy.

The plaza, now “drenched with blood,” was an open-air morgue. Dead and dying lay prostrate as solemn testimony to pigheaded political madness.

Rattling Sabers & Lathered Horses

In a contemporary letter delivered to the U.S. Secretary of State, the body count was gauged: “At present writing it is known that seven persons have been killed while the estimate of wounded reaches as high as thirty of whom seven or eight are wounded mortally….” Varying reports place the dead as high as 15 and the wounded upwards of 50. With certainty John Lemon, I.N. Kelley, Fabián Cortes, Felicito Arroyas y Lueras, Sotelo López, Francisco Rodriguez and the “village idiot boy” were dead.

A list of known wounded would include, but not be limited to, Juan Barela, Juan de Dios Saenz, Francisco López, Leandro Miranda, Jesús Cubero, Hilario Moreno, José Quesada, Cesario Flores, Manuel Neváres, Jesús Calles, José Maria Padilla and Jesús Lopez. Absolute numbers are elusive: “….no one ever knew for sure.”

Upon learning of the chaos at La Mesilla, Col. Thomas C. Devin from his Fort Selden headquarters dispatched Capt. William Kelly and Lt. Millard F. Goodwin, at the head of 65 troopers; he’d follow later to manage a proper deployment. The 8th U.S. Cavalry unit rode at the gallop, carrying the flag and showing force in La Mesilla by 10 p.m. If the quietus hadn’t already overtaken excitable revelers, it did so shortly after Lt. Goodwin’s 20-man detachment took position as “peacekeepers” flanking the town’s plaza. Two miles away, in Las Cruces, Kelly’s squad established a stabilizing no-nonsense presence. At last, peace in the valley.

Days later, the election was held—absent an ounce of spilt blood. Democrats carried the day.

The Democratic candidate for Doña Ana County sheriff, Don Mariano Barela (a former sheriff), was successful by a 300-vote margin during the hotly contested election. History reports that the bullet killing the “mentally defective” boy was meant for Barela. Barela went on to serve multi-terms.

Democrat José M. Gallegos won New Mexico Territory’s nonvoting spot in the U.S. Congress. Many supporters of his defeated Republican rival, J. Francisco Chaves, decamped the Mesilla Valley and, in protest, took up residence across the Rio Bravo at Ascension, Mexico.

William Logan Rynerson, a Republican kingpin, who had earlier killed a New Mexico Territory Supreme Court judge, married John Lemon’s widow. No strange bedfellows here: just keeping it within the family—the Republican family.

Bloodbath Politics

No one was ever brought to justice for the La Mesilla bloodbath. Prosecutors were afraid to touch the hot potato of southern New Mexico politics. They didn’t want to get burned—or shot!

The foolish shoot-out on La Mesilla’s plaza, plus other hot political firestorms, delayed the Territory’s statehood efforts. Lethargic law enforcement, political ineptness and closeness to an international border were magnets, making southern New Mexico a “refuge for numerous outlaws driven from Texas and the other States.” The Territory became the “gunfighter proving ground of the Southwest, a blistering cauldron where so many Wild West gunmen made their reputations.”

Saved By a Coin

At 18, Florencio C. Lopez was at La Mesilla’s plaza when the indiscriminate shooting erupted. Unfortunately a stray ball punched through his vest pocket. Fortunately the projectile struck his coin purse, then collided with a coin, causing its rupture, but exhausting the teardrop ball’s energy. Felipe C. Lopez, Florencio’s older brother, was nearby and reacted, saying, “No sons-of-bitches can shoot at my family,” as he drew his pistol, firing at an adversary. Democrat? Republican? That was hush-hush, a family secret. Not any pesky DA’s business. Florencio, besides the bruised rib cage, wasn’t hurt and lived a long adventurous life in the Southwest fighting bronco Apaches and serving as both a New Mexico militiaman and Doña Ana County deputy sheriff.

Hot Lead, Lost Notes and Long Johns

Hearing a roaring outbreak of gunshots outside, seven-year-old Teresita Garcia, ignoring warnings from her clergyman, rushed from the church on the plaza and into the bedlam and bullets overwhelming Mesilla. Trying to make sense from the kaleidoscope of confusion, Teresita hysterically searched for the comforting form of her father Antonio Garcia. She had seen him last trumpeting notes from his prized horn, a member of the Republican band rallying for a march around the plaza.

At the same instant she picked him out of the crowd, her heart almost stopped. Antonio had fallen to the ground, struck by a bullet from someone’s revolver. Hot lead was flying everywhere, and people’s bodies were falling all around her.

Teresita raced for home, a short distance away. Flinging open the door she screamed: “Mama, Mama, Papa has been shot dead!” Antonio’s wife and Teresita’s mother, Soledad Garcia de Bermudez, stopped supper’s preparation, began gently quizzing the tearful Teresita, while at the same time looking for her shawl. She must rush to her husband’s side, regardless the risks.

Soledad dashed for the doorway, only to be met by her visibly distressed husband, who had excitedly and now breathlessly reached home. For the family it was good news. For Antonio it was a heartbreaker. The stray ball had missed him completely but had stuck his favorite instrument with enough force to knock him down. The bullet hole in the brass horn made it utterly useless—unless the aperture was somehow plugged.

Antonio was frantic. Almost panicky he cried, “Mama, Mama, fix it!” Soledad stated the obvious, “I’m not a welder. I don’t know anything about fixing musical instruments.”

Antonio, this time with a reworked idea, hurriedly pleaded, “Get me some linen or wool or cotton or something.” Dutifully, but gloomily, Soledad answered: “Antonio, I have no more fabric. It’s all gone. I’ve been making quilts for the winter. There’s not even a scrap.”

Undaunted, Antonio made his own search. But to no avail. Mama knew best. Not a patch of fabric was in the house. Necessity is the mother of invention—and innovation. Precious time was wasting. Antonio jumped into action. Alone in his bedroom he pulled out his pocketknife, dropped his britches, unbuttoned the flap-door on his red flannel underwear and sliced off a piece of the tailgate. Somewhat proudly he readjusted his trousers and, with a perceptible swagger, walked back into his family’s presence.

Soledad did not wait for instructions; she knew what Antonio wanted. Out came the sewing box, the needle and thread. Wrap after wrap of material, pulled tight and sewed strongly, had solved Antonio’s dilemma. A quick toot as a test proved the bandaged horn could yet blast out loud notes—maybe not good as new, but loud enough for a political bandsman.

With renewed confidence Antonio now bragged, “Those Democrats aren’t going to stop me.” And they didn’t. He rushed back to the warfront on Mesilla’s plaza. Despite the silliness and seriousness then underway, he dodged bullets and blew that horn until the Army’s bugler brought a stop to the politicians’ din.

EXACT SPOT, How to Get There, What to Do.

Old Mesilla, New Mexico

WHERE IT HAPPENED

La Mesilla Plaza: In recognition of its importance to our national history, the plaza was declared a state monument of New Mexico in 1957 and a National Historic Landmark in 1982.

MUSEUMS

Gadsden Museum: Besides exhibiting Antonio Garcia’s horn that he played during the Democrat-Republican fracas, this museum is also home to artifacts donated by the family of Albert Jennings Fountain, the trial lawyer who defended Billy the Kid in 1881.

Dona Ana County Sheriff’s Department Museum: The region’s only museum dedicated solely to law enforcement is home to Pat Garrett’s desk, as well as artifacts and photographs of most former Doña Ana County sheriffs dating from 1854 forward.

CANTINAS GALORE

Double Eagle Restaurant: Constructed in the late 1840s, this building has witnessed the Mexican-American War of 1846 and the confirmation of the Gadsden Purchase on the plaza in 1853 (you can view an 1849 map depicting the Gadsden Purchase area that includes Mesilla). Enjoy aged steaks and margaritas.

Peppers Cafe: The casual side of the Double Eagle, this cafe specializes in Santa Fe-style cuisine, with Green Chile Cheeseburgers and Banana Enchiladas, which you can down with a margarita.

El Patio Cantina: Before he became the “Law West of the Pecos,” Roy Bean and his brother Sam operated this cantina during the 1850s-60s. Today, the cantina offers live music from 2 p.m. until closing time.

La Posta de Mesilla: Constructed in the 1840s, Roy and Sam Bean operated a freight and passenger line to Pinos Altos from this building in the 1850s. Cooking century-old recipes, this restaurant is famous for its chile and its large tequila selection.

WHILE YOU’RE HERE

A decade after Republicans and Democrats clashed on La Mesilla’s plaza, the Mesilla court and jail was where, in 1881, a jury convicted Billy the Kid of killing Sheriff William Brady in Lincoln. Today, it is the Billy the Kid Gift Shop, offering souvenirs and Indian arts and crafts. Hear Sunday mass at the San Albino Roman Catholic Church, originally built of adobe in 1855 and rebuilt to its present structure in 1906.

BEST TIME TO VISIT

Every September, the residents celebrate their Pan-American Fiesta, with parades, music in the famous plaza and culinary delights that include barbecued lamb and frijoles.