In 1847, the western U.S. was a sleepy wilderness populated mostly by American Indians and Mexicans. The region changed virtually overnight when word of frontier gold reached the East. Some 200,000 restless souls, mostly men, but some women and children, traveled to the untamed lands, primarily to California, during the first three years of the Gold Rush.

While fortunes were made and lost daily, gold seekers also sought out crude entertainments provided by ragtag bands, bear-wrestling and prize-fighting exhibitions, gambling dens, saloons, brothels and dance halls. After a while, the miners and merchants longed for more polished amusements. Theatres, backstreet halls and jewel-box-sized playhouses were built and stayed busy; their thin walls resounded with operas, arias, verses from William Shakespeare and minstrel tunes.

The pioneers’ passion for diversion lured brave actors, dancers, singers and daredevils west. Bored miners were willing to pay high sums to these entertainers, especially to the females.

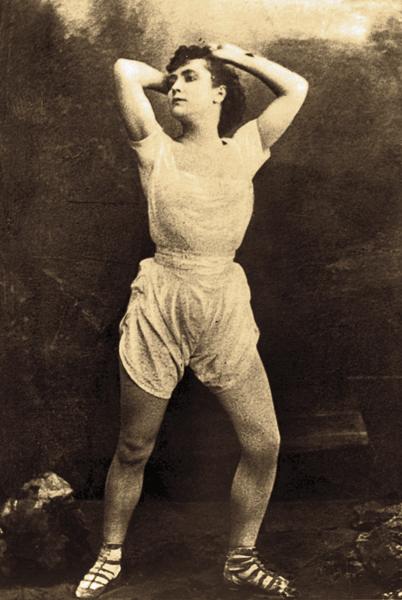

In the boomtowns during the mid-and-late 1800s, one of the most celebrated female entertainers was Adah Menken. Critics claimed she had one of the most beautiful figures in the world.

On August 24, 1863, the elite of San Francisco, California, flocked to Maguire’s Opera House. Ladies in diamonds and furs rode up in handsome carriages; gentlemen in opera capes and silk hats strutted stylishly. This was an opening night the city had never before seen. All 1,000 seats in the theatre were filled.

Scandalous on Stage

San Francisco was anxious to see Adah star in the role that was making her famous—Prince Ivan in Mazeppa. Rumors had circled that she played the part in the nude. Eastern newspapers reported audiences had found the scantily clad thespian’s act “shocking, scandalous, horrifying and even delightful.”

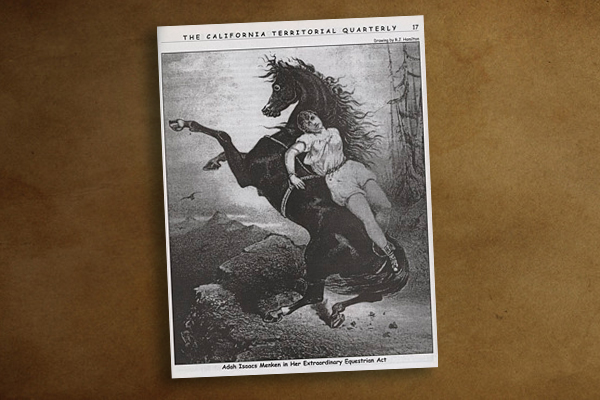

The storyline of the play was taken from a Lord Byron poem, in which a Tartar prince is condemned to ride forever in the desert, stripped naked and lashed to a fiery, untamed steed. Adah insisted on playing the part as true to life as possible.

The audience waited with bated breath for the actress to walk out onto the stage. When she did, a hush fell over the crowd. The beauty with the curly, dark hair and big, dark eyes wore a flesh-colored body nylon and tight-fitting underwear.

During the play’s climatic scene, supporting characters strapped the star to the back of a black stallion, which then raced up the narrow runway between cardboard mountain crags. The audience responded with thunderous applause. Adah had captured the heart of another city in the West.

A Star is Born

Adah was born Adois Dolores McCord on June 15, 1835, in New Orleans, Louisiana, to her French Creole mother and her highly respected, free black father. Prejudice against Adah’s ethnicity plagued her early career. Theatre owners familiar with her heritage refused to hire her. She created stories about her upbringing, apparently to secure work. The truth about her roots was not uncovered until the early 1900s.

At 20, Adah began her quest for stardom in Liberty, Texas. She gave public readings of Shakespeare’s works, wrote newspaper articles and poems, and taught dance classes. She searched for a rich husband to support her acting career by placing an advertisement in the Liberty Gazette newspaper on November 23, 1855:

“I’m young and free, the pride of girls With hazel eyes and ‘nut brown curls’ They say I’m not void of beauty— I love my friends and respect my duty— I’ve had full many a BEAU IDEAL, Yet never—never— found one real— There must be one I know somewhere, In all this circumambient air; And I should dearly love to see him! Now what if you should chance to be him?”

Alexander Isaacs Menken, a well-to-do pit musician and conductor, was touring the Texas Panhandle when he came upon Adah’s delightful poem. He wrote to her, and the two met, instantly firing one another with passion and ambition. They were married the following April, in Galveston.

Soon after Adah and Alexander said, “I do,” Adah began acting in supporting roles at the Liberty Shakespeare Theatre. With her husband’s financial help, she moved on to lead roles at the Crescent Dramatic Association of New Orleans in Louisiana.

Alexander worshiped his bride, and Adah was quite taken with him, but their notions of married life were diametrically opposed. Alexander wanted a stay-at-home wife who would make his meals and raise his children. Adah was not at all interested in domesticity; she wrote in the Liberty Gazette: “women should believe there are other missions in the world for them besides that of wife and mother.”

Regardless of his opinions, Alexander came to rely on Adah’s income when he lost his fortune in ill-advised real estate investments. Adah tried to bolster his demoralized spirit by naming him her manager, but new marital troubles were on the horizon. Alexander became jealous of the adoring young men who gathered at the stage door, roses in their arms for Adah. He distanced himself from his popular, independent wife when she wore pants and smoked in public, which proper women of the time absolutely did not do. Once he could no longer tolerate her habits, the pair separated.

Adah got over the collapse of her marriage by going on another acting tour. She traveled across the Great Plains and the West, performing in the plays Great Expectations and Mazeppa. Dressed in risqué costumes, the immodest Adah packed houses in boomtown theatres, prompting overeager critics to state, “Prudery is obsolete now.”

Adah was one of the first actresses to recognize the value of photography for both publicity and posterity. Playbills featuring her picture preceded her arrival, appearing in every newspaper anywhere near where she was set to perform. Her portrayal of the Prince of Tartar in Mazeppa and a lovesick sailor boy in Black-Eyed Susan brought rave reviews from theatre critics. The newspapers also printed the poems and articles she wrote when she wasn’t on stage.

Critics called her a second Lola Montez, comparing her to the bawdy Gold Rush performer known for being without inhibitions. One observed of Adah:

“her style of acting is as free from the platitude of the stage as her poetry is from the language.”

As her fame increased, Adah gained and lost two more husbands, and gave birth to two children. She never stopped working, though, and became known as the “Frenzy of Frisco.” In California, San Francisco adopted her as its favorite daughter. The St. Francis Hook and Ladder Company made her an honorary member of its firefighting brigade, presenting her with a beautiful belt and serenading her to the tunes of a brass band.

Adah wasn’t satisfied with being only the “Frenzy of Frisco.” She wanted to be the frenzy of the entire West. In 1864, she took to the road again, traveling east to Virginia City, Nevada.

The Gold Hill Daily News touted the actress’s arrival on the front page: “She has come! The Menken was aboard one of the Pioneer coaches which reached Gold Hill this morning, at half-past eleven o’clock. She is decidedly a pretty little woman, and judging her style we supposed she does not care how she rides—she was on the front seats with her back turned to the horses. She will doubtless draw large houses in Virginia City, with her Mazeppa and French Spy in which she excels any living actress.”

Adah opened her Virginia City show on March 2, 1864. Tickets ranged in price from $1.00 for a single seat to $10.00 for a private box. The theatre was packed on opening night. Some attendees were forced to stand in the aisles, and hundreds were turned away.

Adah earned an estimated $150,000 from her 29 Nevada shows. When she left Virginia City, lovesick miners gave her a silver brick valued at $403.31 and stamped: “Miss Adah Isaacs Menken from friends of Virginia City, Nevada Territory—March 30th, 1864.” They also named a local mine after her and formed the Menken Shaft and Tunnel Company. The company’s stock certificates bore a picture of a naked lady bound to a galloping stallion.

The actress then traveled to Europe, still starring in Mazeppa, and toured Paris and Vienna. Although her talent was appreciated abroad, she never felt more loved by an audience as she had when she performed in California and Nevada.

Adah’s Last Nude Scene

In June 1868, while acting out her famous “nude” scene, the horse Adah was bound to ran too near a stage flat and the flesh of Adah’s leg was torn. A doctor found a cancerous growth had formed as a result of the accident. Six weeks later, Adah collapsed from tuberculosis. She died on August 10, 1868, and was buried in Paris, France. The actress was only 33 years old.

Adah’s talent and daring had made her world famous and the toast of princes and poets of two continents. Among some of her most loyal fans were novelist Charles Dickens, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and journalist Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain.

The journalist’s description of her performance, published in the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City, Nevada, is considered the best surviving account of Adah in action: “She is a finely formed woman down to her knees,” Twain wrote in September 1863. “…Here every tongue sings the praises of her matchless grace, her supple gestures, her charming attitudes. Well, possibly, these tongues are right…. she works her arms, and her legs, and her whole body like a dancing-jack; her every movement is as quick as thought…. If this be grace then the Menken is eminently graceful.”

Chris Enss is a New York Times bestselling author who has written more than 20 books on the subject of women in the Old West. Adah Menken is one of the more than dozen actresses featured in Entertaining Women, her book due out this October.

Photo Gallery

– All images True West Archives –