Angola, Louisiana, might not be considered the West to some folks, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen any roundup get as Western as its prison rodeo-and I’ve attended plenty of rodeos.

The Angola Prison Rodeo opens with an event called Bust Out, in which all six chutes open simultaneously, releasing felons on bulls. The last man on wins. Keep in mind that most of these inmates have as much experience, and business, riding roughstock as I do. It’s wild, and it gets wilder.

Angola’s prison rodeo started in 1965, and it has grown from a small event, not open to the public, to the “Wildest Show in the South,” with a stadium that packs in 7,500 paying spectators. The rodeo is held one weekend in April (17-18 in 2010) and every Sunday in October, complete with an arts and craft festival (for sale: spurs handcrafted from prison toilets) and plenty of Southern prison cookin’, from po-boys to fried fatback.

Louisiana’s only maximum security prison houses more than 5,100 inmates—52 percent serving life sentences. And “life means life in Louisiana,” prison officials keep telling me.

Angola’s prison got its start in 1880, when ex-Confederate Maj. Samuel James bought an 8,000-acre plantation and began keeping inmates in the Old Slave Quarters. James had been awarded the state pen’s lease in 1869. Prison conditions were brutal, about a thousand times worse than depicted in the Steve McQueen movie Nevada Smith. You can get a feel for that at the prison museum, which opened in 1998. The T-shirts inmates are selling at the rodeo put it bluntly: “Angola Ain’t No Place To Be.”

Unless you’re visiting for the annual rodeo, of course.

“Rodeo brings out the best in the inmates,” warden Burl Cain says. “It gives them a chance to be cheered for. We’re generating hope instead of despair.”

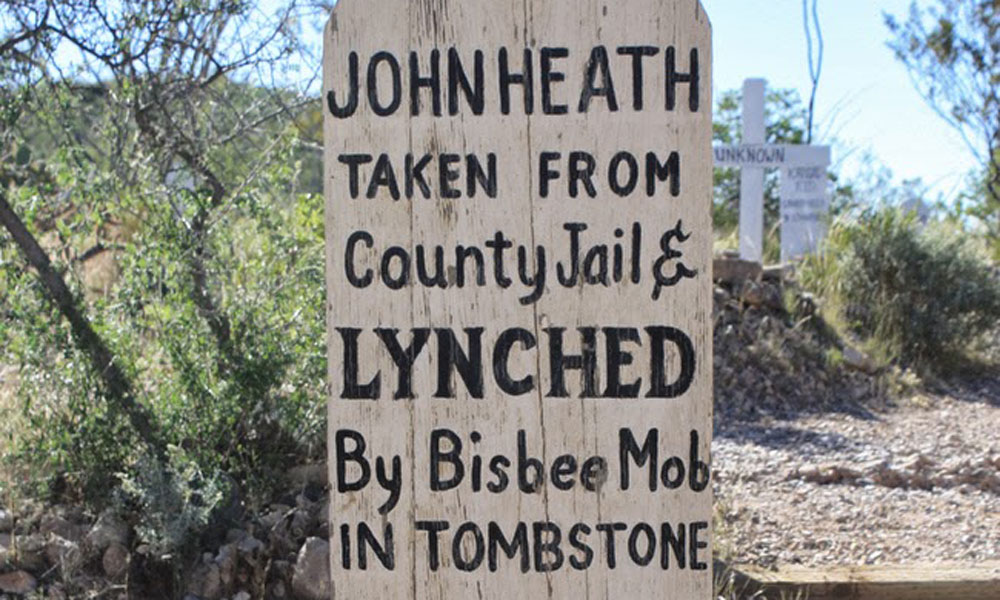

Huntsville Slammer

Alas, the Huntsville slammer no longer puts on its rodeo. That event ended in 1986, but you still have plenty to see at the Texas State Penitentiary in Huntsville, alias Huntsville Unit, alias the Walls Unit. After all, these brick walls once held notables such as Kiowa chief Satanta, musicians David Crosby and Huddie Ledbetter, psycho gunfighter John Wesley Hardin and a Great Depression-era bank robber named Clyde Barrow.

“A lot of our visitors say they’re kin to either John Wesley Hardin or Clyde Barrow,” says museum director Jim Willett, as he shakes his head in disbelief that the list of relations could be so long.

The museum opened in 1989 and moved to its current location off Interstate 45 in November 2002. Visitors to the museum number about 23,000, or 13.5 times the maximum (all-male) inmate population. Museum displays—including “Old Sparky,” the electric chair used on 361 prisoners between 1924-64—tell the story of the prison, which opened for business in 1849.

Visitors can also take a driving tour around the prison, where you can see the now-defunct rodeo arena. Farther from the walls is Peckerwood Hill Cemetery, the 22-acre boneyard that marks the resting place of more than 1,700 prisoners, including Satanta, who committed suicide at the prison in 1878 (his remains were later moved to Fort Sill in Lawton, Oklahoma).

OK’s Prison Rodeo, Not So Okay

Before statehood, convicts in Oklahoma and Indian territories were shipped to the Kansas state pen in Lansing. But since 1908, the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester has been home to inmates. These days, you’ll also find death row and a museum.

You used to be able to find a “behind the wall” prison rodeo too, but not this year. In February, the McAlester Chamber of Commerce announced that the Oklahoma State Prison Rodeo would be suspended for 2010 because of state budget shortfalls.

August would have marked the 70th anniversary of the rodeo, which brought in record attendance last year. “Unfortunately, the reality is we just don’t have the number of correctional officers available to transport and secure the offenders who participate in the event,” warden Randy Workman says.

Oh, well, at least the prison museum’s still operating. Or was, at least, as of press date. The small museum tells the story of the state pen, including the 1973 riot that left three inmates dead, 21 inmates and guards hurt, 12 buildings burned and an estimated $30 million in damages.

Dept. of Corrections for a Cannibal

Since the Territorial Prison in Cañon City (later named Colorado State Penitentiary) housed its first guest in 1871, it has confined a number of inmates, including Colorado’s most famous cannibal, Alferd Packer. Packer’s cell tells his story, while 31 other cells inside the circa-1935 Women’s Correctional Facility—now the Museum of Colorado Prisons—relate the history of the prison and the stories of its prisoners.

Also on display are the gas chamber and the prison’s last hangman’s noose. The museum is next to the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility, a.k.a. “Old Max.” When I was walking toward it, a guard racked his machine gun from his post on the wall. Showoff. He didn’t look as tough as the guard at the Walls Unit in Huntsville who told me to get my butt off state property.

Wyoming’s Big Houses

I don’t think Wyoming has as big a crime problem as Texas, but it has two prison museums worth seeing. First stop, the Wyoming Territorial Prison State Historic Site in Laramie.

“The Big House Across the River”—and big it was, built of white and red stone in 1872—housed more than 1,000 men and at least a dozen women. The Wyoming Territorial Prison became the Wyoming State Penitentiary in 1890, then housed sheep and cattle for the University of Wyoming until 1989, when the good citizens of Laramie decided the Big House needed to be restored. The prison opened as a historic site in 1991. That’s a good thing too. After all, this is the pen that once housed Butch Cassidy.

Today, visitors can tour the prison, as well as the warden’s house and the broom factory, where inmates made brooms between 1892 and 1902. Wyoming’s brooms swept up dirt across the Western United States and as far away as Honolulu, Japan and Hong Kong.

In 1903, inmates were transferred to the new state pen in Rawlins, so I’m off to the Wyoming Frontier Prison museum. The 1901 prison incarcerated some 13,500 folks during its 80-year history.

Guided tours at the museum take visitors through the dark, depressing but enlightening walls. This prison also had a broom factory, at least, until inmates burned it down during a 1917 riot. Baseball, not rodeo, was the popular sport among prisoners and guards. And between 1949 and 1981, the year the prison closed, inmates manufactured, you guessed it, license plates!

Montana’s Medieval Prison

I’m hoping to find a deal when I pull into the Old Prison Museum gift shop in Deer Lodge, Montana. Maybe a horsehair-stitched belt for …oh, well, that’s a bit out of my budget. But the Old Prison Museum is a deal; you can take a self-guided tour of the compound that housed inmates from 1871 until it closed in 1979.

The walls weren’t always stone. Originally surrounded by a 12-foot-high wooden fence, the Deer Lodge prison got a facelift under the direction of Frank Conley, who served as warden from 1890 to 1921. Warden Conley wanted his inmates to work, so he had them construct a massive stone wall 4 1/2-feet thick. Inmates made 1.2 million bricks to complete the 1896 cell house and other buildings. The place looks like a medieval castle.

How tough was it here? Well, check out the display of work shoes, which inmates with escape on their minds were forced to wear. They had concrete soles and weighed about 20 pounds each.

From Cash’s Folsom to “The Rock”

Folsom prison may offer more than Johnny Cash, yet the Folsom Prison Museum (actually, its official name is the Retired Correctional Peace Officers Museum at Folsom State Prison, but that’s a mouthful) in California’s Gold Country pays a lot of tribute to the Man in Black and his famous live 1968 album.

Built to relieve overcrowding at San Quentin—where Cash made another dynamite live album in 1969—Folsom opened for customers in 1880. The first escape came about the same year. That’s because the blue granite wall did not yet surround the prison (which also did not have any heating or plumbing). The Greystone Chapel Cash sung about, written by inmate Glen Sherley, was completed in 1903, and the walls finished 20 years later.

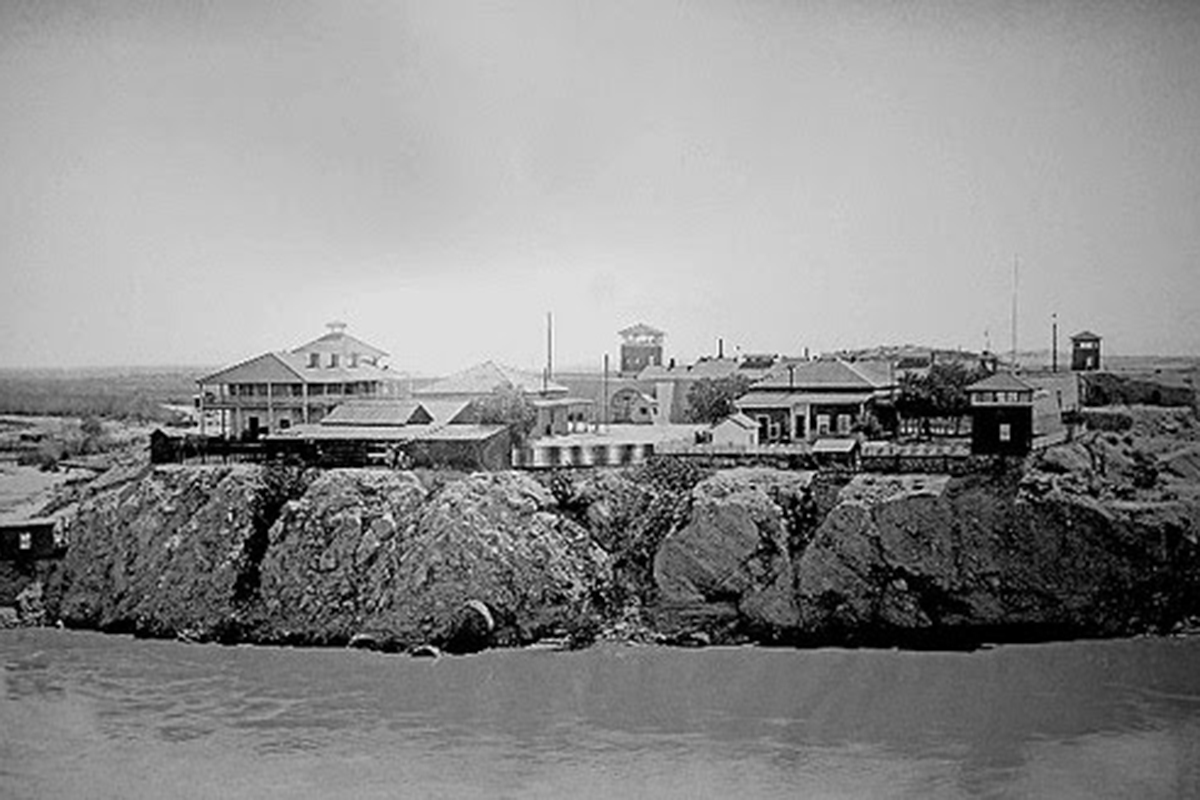

Another famous prison, down the road and offshore from San Francisco, is the famous Alcatraz Island. Used by the military as early as 1850, Alcatraz began taking in prisoners in 1861. A jail was built in 1867, and the following year Alcatraz was designated to house military prisoners. The Department of Justice acquired “The Rock” in 1933, and the island became a federal prison the following year. Al Capone spent some time here. So did Machine Gun Kelly, Alvin Karpis and the “Birdman of Alcatraz” himself, Robert Stroud.

The pen closed in 1963 and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1986. To get there, you’ll need to book a ticket through Alcatraz Cruises, located at Pier 33 not far from San Francisco’s famous Fisherman’s Wharf. When packing for the trip, remember what Mark Twain said: “The coldest winter I ever spent was a summer in San Francisco.”

Cold has never been used to describe the final stop on this prison tour.

Arizona’s Territorial Prison Saved

Talk about a stay of execution: The Yuma Territorial Prison State Historic Park was set to close its doors on March 29. Earlier this year, the Arizona State Parks Board voted to close 13 parks because of budget reductions. Yuma was not the only park that drew a black bean. The historic sites of Fort Verde, Tubac Presidio, Lost Dutchman, Picacho Peak and even the Tombstone Courthouse are scheduled for closure.

The closure would have been not only a blow for Yuma—the prison is the city’s best tourism draw— but a slap in the face to Western history lovers, and even Western history. But on March 10, Yuma Mayor Al Krieger announced that, based on projections of tickets and merchandise sales, the community will reach its goal of raising $50,000. That amount was raised to match the $50,000 the Yuma Crossing National Heritage Area gave to save the museum. “That means that the Yuma Territorial Prison will remain open and operating,” Krieger says.

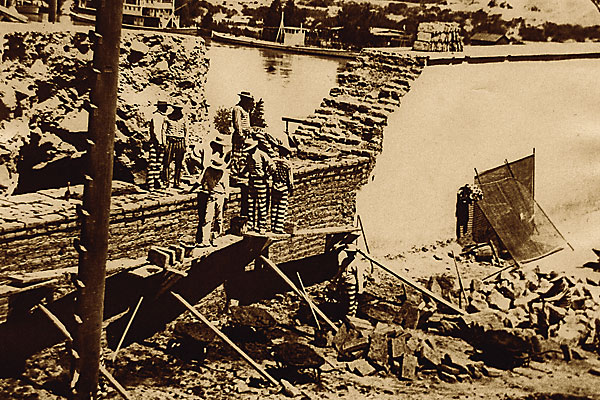

The first seven inmates entered the hot, desolate, brutal Territorial Prison in Yuma on July 1, 1876. Everything you’ve ever heard about Yuma is likely true, although docents try to convince me that Yuma was a model prison, and the inmates were treated humanely. It was even home to one of Arizona’s first public libraries. I wonder if they had Elmore Leonard’s great 1972 novel about Yuma, Forty Lashes Less One, available for checkout.

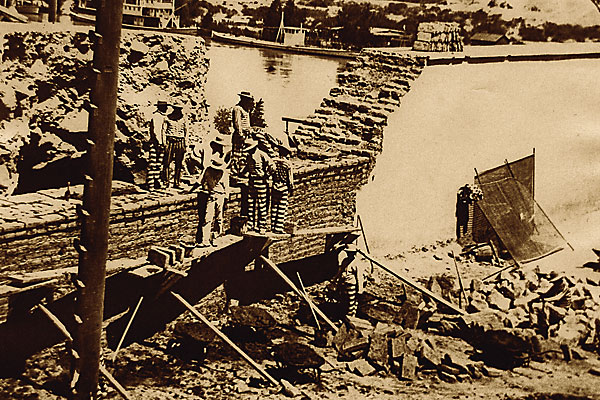

Over its 33 years, Yuma’s prison housed 3,069 prisoners, 29 of those women, including stagecoach robber Pearl Hart. Twenty-six of those prisoners escaped, though only two managed to get out from behind the prison walls. In 1907, overcrowding forced construction of a new pen in Florence, and the last prisoner left Yuma on September 15, 1909.

Thank goodness the museum was saved. A prison road trip just wouldn’t be the same without seeing those iron bars in Yuma.