January 11, 1886

January 11, 1886

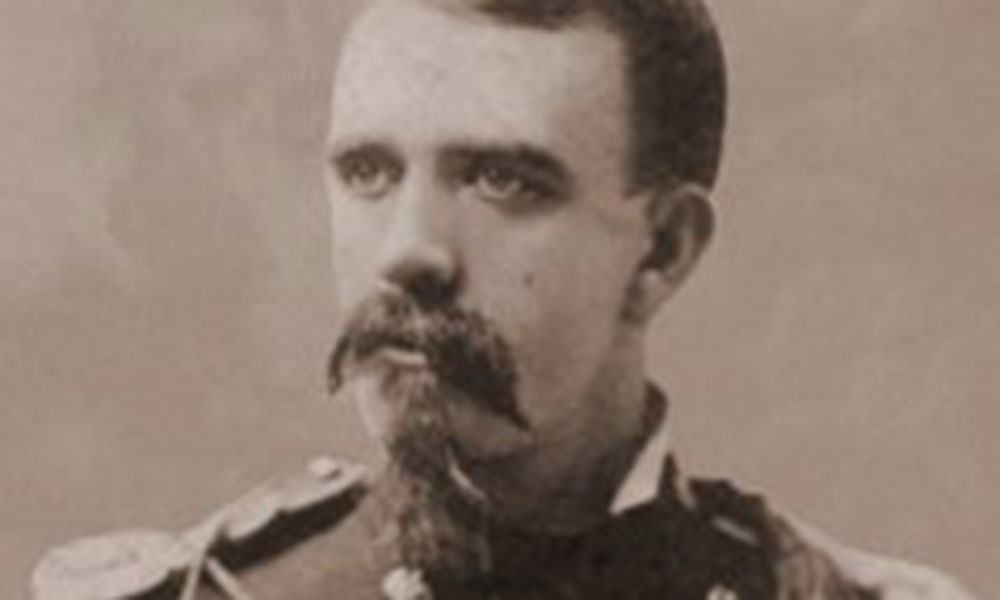

Captain Emmet Crawford is on the brink of victory. Yesterday, his punitive raiding party of three officers, one medic, one interpreter and 79 Apache scouts completely surprised and captured all the provisions and horses of Geronimo’s stronghold at a rugged place called Espinosa del Diablo—Devil’s Backbone—in Sonora, Old Mexico (see map).

On this foggy, rainy morning, Capt. Crawford is preparing to meet with Naiche and Geronimo to discuss a possible Apache surrender, when, at 7:30 a.m., Apache scouts spread the alarm on the approach of a 128-man Mexican force, including a contingency of Tarahumara Indians, enemies of the Apache.

Before Crawford or his men can react to the news, the Tarahumaras, taking up positions in the rocks above the camp, send in a volley from their Springfield breechloaders. Three Apache scouts are wounded, one of them in his sleep.

Several Apache scouts return fire from a ridge east of the camp, while Capt. Crawford runs with Lt. William Shipp, Lt. Marion Maus and Chief of Scouts Tom Horn to find out what is happening.

Maus and Horn repeatedly identify themselves as American soldiers. Scattered firing continues for 15 minutes, but with the constant pleading of the American officers, it finally stops.

Incredibly, the three Americans —Crawford, Horn and Maus—are unarmed as they proceed out of the rocks to meet 10 heavily armed Mexican troops under the command of Maj. Mauricio Corredor (the major is a well-known Mexican soldier who is credited with taking down Chiricahua Apache Chief Victorio roughly six years earlier).

Horn is about 100 feet in advance of Maus when he sees Crawford waving a white handkerchief as a sign of peace. Corredor and four of his men ignore Horn and walk past him.

In Spanish, Lt. Maus says, “Don’t you see we’re American soldiers? Look at my uniform and the captain’s.”

While the officers powwow, the Apaches and the Tarahumaras begin trading insults and threats. When the officers hear the sharp snap of the breechloaders, both Crawford and Corredor implore their men not to fire. Crawford jumps up on a five-foot boulder and once again waves his truce flag.

A Mexican sniper fires, hitting Crawford in the forehead. Corredor turns and smiles at Horn, then fires at the unarmed scout, hitting Horn in the arm. One of the Apache

scouts, Dutchy, shooting Corredor through

the heart.

Three Chiricahuas spring from hiding, close to the Mexican line, and shoot. Thirteen Apache bullets pierce the body of Corredor’s second in command, Lt. Juan de la Cruz.

The Tarahumaras attempt to flank the Americans, but Maus’s company of scouts drive back the attackers.

Without leadership, the Mexican forces falter and then flee with their wounded to a series of hills about 300 yards away.

The next day, Maus opens up a dialogue with the attackers. He goes to the enemy’s camp, along an interpreter, and brokers a cease-fire.

The fighting is over, but the U.S. border is a long ways from the

Devil’s Backbone.

– True West Archives –

High Praise for Apaches

Maus is effusive in his praise of the Apache scouts who accompanied the command into Mexico, saying, in part, “Their system of advance guards and flankers was perfect, and as soon as the command went into camp, outposts were at once put out, guarding every approach. All this was done noiselessly and in secret, and without giving a single order.” But he also admits, “It was impossible to march these scouts as soldiers, or to control them as such, nor was it deemed advisable to attempt it.”

Unfortunately, when neither the Apaches nor the officers adhered to the above system, it proved disastrous.

The Night Stalkers

A few days before the gunfight, Crawford and his command left their camp in Nacori. They ditched their horses and proceeded on foot, bringing along three of their “toughest mules.”

Fording the Aros River, they discovered a main trail, about six days old, which led east into a country “rough beyond description.” They marched mostly at night and suffered from the cold, making it impossible to sleep. At one place, Maus said they saw a leopard, spotted and as large as a tiger.

At sunset on January 9, their Apache guide Noche sent word that the hostile camp had been located 12 miles away.

The men rested for 20 minutes. Unwilling to build a fire for fear of discovery, they ate hard bread and raw bacon. A doctor and one of the interpreters were worn out and couldn’t continue.

Six hours later, after crossing and recrossing the turbulent river, and making their way “over solid rock, over mountains, down canyons so dark they seemed bottomless,” the rest of the soldiers and scouts finally neared the camp. Near dawn on January 10, after marching continuously for 18 hours, the men spread out to surround the camp. Maus said, “Noiselessly, scarcely breathing, we crept along.”

Before Maus could get into position, the “braying of some burros was heard. These watchdogs of an Indian camp are better than were the geese of Rome.” Immediately the camp “was in arms.” “We fired many shots,” Maus reported, “but I saw no one fall.”

“That Beardless Youth”

To some historians, the fight on the Devil’s Backbone on January 11 was the highlight of Tom Horn’s career. Horn biographer Larry D. Ball is among them. He tells us, “The morning of the fight was rainy and visibility very poor. Crawford did not put out sentinels, but permitted everyone—exhausted from the previous march to the hostile camp and the following battle—to sleep in. It was a tragic error on Crawford’s part. Since the Chihuahuan militiamen thought they had surprised the renegades’ camp, they did not hesitate to attack. Only after the Mexicans opened fire for a second time did it become apparent that they were a treacherous lot.

“Tom Horn was the first representative of Crawford’s command to walk out unarmed to try to persuade the attackers to back off. He was the Spanish interpreter, although Maus could also speak Spanish.

“In subsequent official Mexican documents, they praised Tom Horn’s bravery, calling him ‘that beardless youth.’ Horn was clean shaven and still only 25 years of age. He continued throughout the confrontation to communicate with the Mexican camp. However, he balked at leading some horses from the American side into their camp, believing the Mexicans should come and fetch the animals themselves.

“Furthermore, he, like the scouts and white soldiers, were peeved at having to turn over valuable army mules in order to obtain Maus’s release [Maus had been “detained” when he went to talk to the Mexicans, and they demanded mules in exchange for his release].

“Perhaps, Horn’s biggest contribution to this tragic expedition was assisting Lt. Maus, now in command, in getting the column out of Sonora unharmed. Since Horn spoke Spanish, he assisted Maus in negotiating with Mexican officials and attempting to keep the Apache scouts in line. The scouts were outraged at not having the freedom to wipe out the Chihuahuans and did commit some depredations on the retreat to the border.

“While Maus did receive the Medal of Honor, he recommended Horn for some sort of recognition in the general order praising all the participants, but this request was refused.

“Unfortunately, Horn’s autobiography, Life of Tom Horn: Government Scout and Interpreter (posthumously published in 1904), has served as the primary medium for publicizing his frontier activities. It is almost always untrustworthy—in varying degrees, from gross exaggerations to outright prevarications. What is unfortunate is that he did not have to exaggerate. His accomplishments, including praises from various Army officers, were sufficient if he had only told the truth.”

Dutchy Pays for Avenging Crawford’s Death

A deputy U.S. marshal from Tombstone, Arizona (Maus does not name him), surprised the Crawford detachment in Nacori. The marshal had traveled several hundred miles into Mexico to arrest the Apache scout Dutchy on a murder warrant (he was accused of killing a miner near Fort Thomas).

Crawford asked the marshal to “delay the arrest till I may be near the border where protection for myself, officers and white men, with my pack-trains, may be afforded by United States troops other than Indians.”

Maus claimed the scouts were “intensely excited, and under the circumstances the marshal did not wish to attempt to arrest Dutchy, and returned [to Arizona] without delay.”

Ironically, in the fight against the Chihuahuans on January 11, 1886, Dutchy would be the one to dispatch the sniper who shot Crawford.

After Geronimo’s surrender to Gen. Nelson A. Miles in September, Dutchy was removed to Florida along with the other Chiricahuas. He died in captivity.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

After the January 11 battle, Tom Horn and Marion Maus met with the Mexican officers and allowed medical aid for wounded Mexicans. Captain Emmet Crawford, while still alive, remained unconscious. The next morning, the Mexicans called Maus to their camp to discuss the use of mules to transport their casualties. After he arrived, they refused to let him leave and demanded to know his right on Mexican soil. Only after they got the requested mules did the Mexicans permit Maus to depart.

On January 15, Geronimo, who had watched the fight from a bluff nearby, refused to surrender to Maus. In March, Geronimo agreed to discuss a surrender with Gen. George Crook, but to no avail. Nelson A. Miles would be the general who secured the chief’s surrender in September.

Crawford died on January 18 and was buried at Nacori in Sonora, but his body was later transported to his home in Kearney, Nebraska (Crawford, near Fort Robinson, is named in his honor).

Crook called Crawford’s death an “assassination.” Secretary of War William Endicott termed the deed “utterly unjustifiable.” Congress demanded reparation and punishment of the guilty parties, but on April 1, Mexican President Porfirio Díaz countered that his troops did not recognize Apaches as U.S. troops. The Mexican authorities also claimed the Apache scouts were guilty of stealing livestock. (On January 10, Crawford had captured Geronimo’s stolen stock, some 300 horses, and he was in possession of it during the attack the next day.)

In 1887, Mexico returned the animals taken from Maus and gave a draft of $500 to cover their use. The U.S. Army awarded the Medal of Honor to Maus in 1894 for his actions in the fight. As for the fate of his compadres, Lt. William Shipp was killed in the battle for San Juan Hill in 1897, while Tom Horn was hanged for murder in 1903.

Recommended: The Apache Wars by Paul Andrew Hutton, published by Crown; Tom Horn in Life and Legend by Larry D. Ball, published by University of Oklahoma Press; and From Cochise to Geronimo by Edwin R. Sweeney, published by University of Oklahoma Press