For a guy who never existed, Zorro has had quite a year.

For a guy who never existed, Zorro has had quite a year.

April saw the publication of Zorro, the first serious fictional treatment of America’s first masked superhero, by the Peruvian born, Chilean raised and now California resident Isabel Allende. Allende’s novel is a landmark; Diego de la Vega, after more than 80 years, finally has an origin and a background. (Allende has given him not only noble Spanish blood but a mother who is a full-blooded Indian.) In May, the artist-writer team of Don McGregor and Sidney Lima resumed their acclaimed Zorro comics series. In September, the original Zorro story, published in 1919 as “The Curse of Capistrano,” was reissued by Penguin Classics under the title The Mark of Zorro. And, in the biggest Zorro news of all, November marks the release of The Legend of Zorro, the follow up to the hugely successful 1998 film, The Mask of Zorro.

You can call it a comeback, but in truth, in the 86 years since his creation, Zorro has never really gone away. He is both the first hero of the Old West—his adventures begin before 1820, when California was still part of the Spanish empire—and the last—since California, both literally and symbolically, is at the end of American’s Western dream. “He’s the real all-American hero,” says Antonio Banderas, who has played him in both recent films, “and America’s first Spanish hero. He’s an American original.”

The character of Zorro—“fox” in Spanish, as everyone ought to know by now—originated not in Mexico or Spain, but in the mind of a New York journalist and pulp writer Johnston McCulley. McCulley moved to southern California in 1908 and picked up something of the color and lore of the provincial times, though nothing at all of its history. No one is sure exactly who the literary inspiration for Zorro was, though a likely candidate is the hero of Baroness Emmuska Orczy’s 1905 adventure-romance pot boiler, The Scarlet Pimpernel, about a masked Englishman who rescues French aristocrats from revolutionary fanatics. But the Scarlet Pimpernel fought for the aristocracy, while Zorro fights against the nobility for the common man; he was an outlaw and almost certainly was modeled, at least in part, on legendary California bandits such as Joaquin Murieta and Solomon Pico.

The former, in particular, engendered a cult which has lasted to this day. Said to be the terror of Gold Rush-era California, Murieta was allegedly killed in 1853. In 1966, he was the subject of a play by Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, The Splendor and Death of Joaquin Murieta. In the 1980s, when Latino activism in California was at its peak, it wasn’t uncommon to see the name “Joaquin Murieta” spray painted on walls in East Los Angeles, as if his ghost was still watching over his old territory.

Since much of the Murieta story that survives is also legendary, it’s no surprise that Zorro and Joaquin have sometimes been seen as parallel characters. In the late 1950s, the hero of Walt Disney’s TV series Zorro, played by Guy Williams, was often seen as the “good” rebel while Joaquin Castaneda, clearly modeled on Joaquin Murieta, was presented as the example of the irresponsible “bad” rebel who Zorro constantly had to lecture to and keep in line. In an ingenious touch, the screenwriters of The Mask of Zorro had Joaquin Murieta’s brother, Alejandro, played by Antonio Banderas, become the new Zorro after Joaquin’s death. And now, in The Legend of Zorro, Alejandro’s son, played by Adrian Alonso, is named Joaquin after his uncle. The story hints that he will someday inherit both traditions.

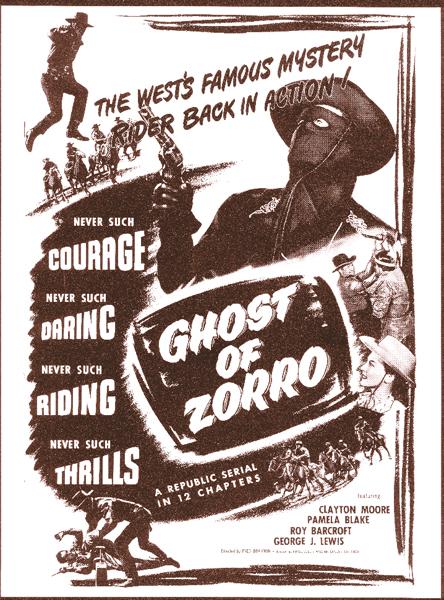

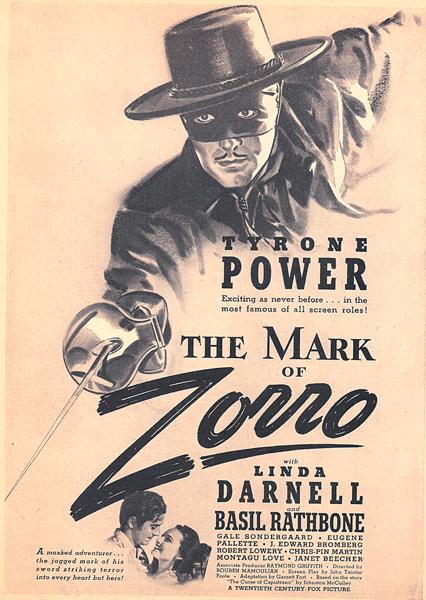

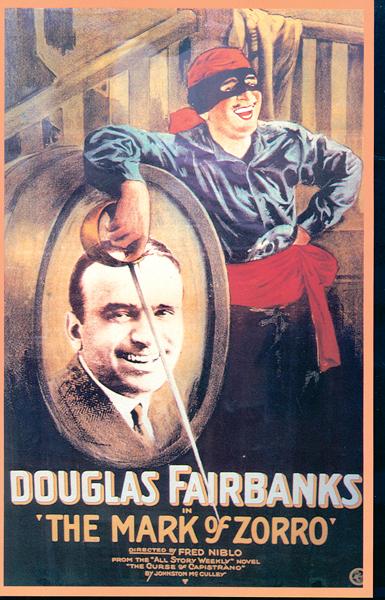

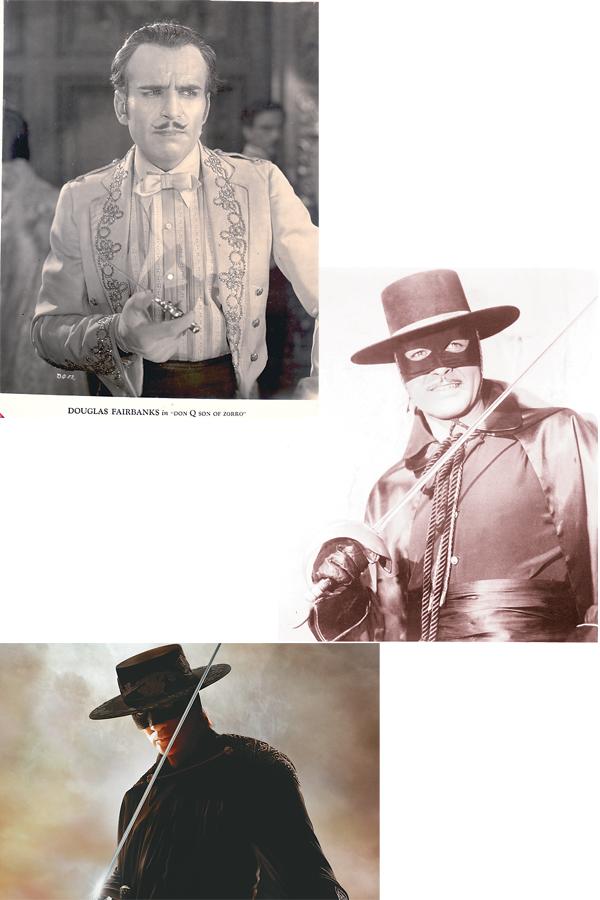

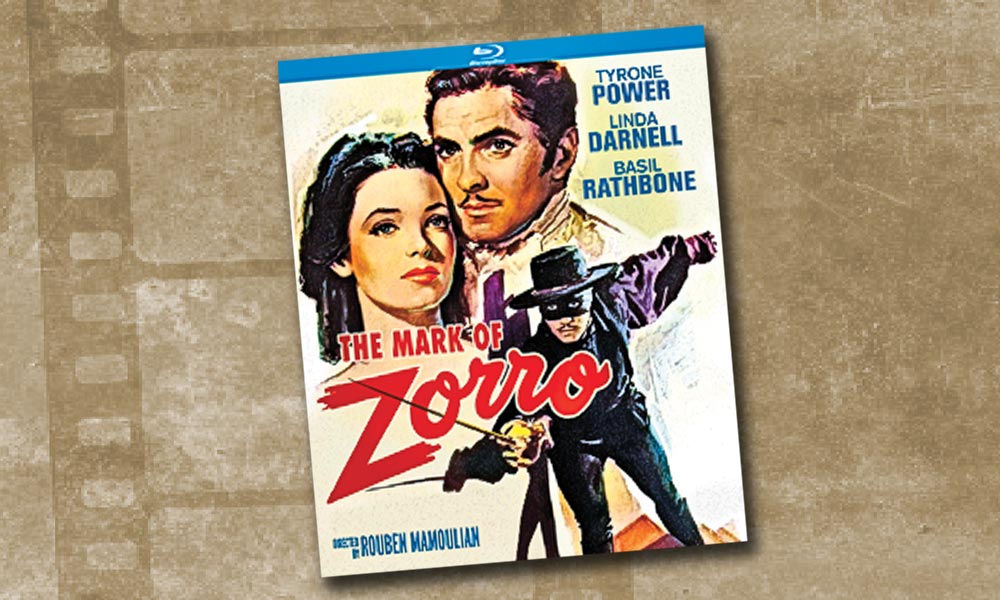

The Zorro we have come to know and love wasn’t a product so much of birth as evolution. McCulley’s first Zorro, written for a pulp adventure magazine, was simply a Spanish gentleman in a mask fighting for the rights of the downtrodden Mexican peasants and Indians. In 1920, a year after McCulley’s first story, Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. changed all that, transforming him into a black-suited acrobatic daredevil (audiences oohed and aahed at Fairbanks’ amazing athletic stunts) in the original The Mark of Zorro. After the enormous success of Fairbanks’ film, McCulley revived the character, writing more stories for the pulps and reshaping his literary hero in Douglas Fairbanks’ image. Over the decades, that image has been embellished by numerous actors from Tyrone Power (in the remake of The Mark of Zorro) to Guy Williams in the late 1950s’ Walt Disney TV series to Alain Delon in 1975’s Zorro. There has even been a gay Zorro—a gay caballero?—played by George Hamilton in the hysterically funny 1981 spoof, Zorro: The Gay Blade.

Along the way, Zorro has been the inspiration for dozens of crime fighters. Bob Kane, Batman’s creator, paid homage to him by having Bruce Wayne’s parents murdered while coming from a theater where The Mark of Zorro was playing. (This must have been the Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. version, as Batman was created in 1939 and the Tyrone Power remake wasn’t released until 1940.)

Of course, the most recent and most successful incarnation of Zorro is Antonio Banderas—amazingly, the first Hispanic actor ever to play the role, though several Hispanics have been cast as the villains, most notably Ricardo Montalban in the 1974 TV remake of The Mark of Zorro. Montalban was also the first Hispanic actor to voice his discontent over the hero’s role going to a non-Latin actor (in this case, Frank Langella), while a Latino was the bad guy.

In the new Zorro movie, Director Martin Campbell says, “We made a conscious effort to infuse some of the legend and lore connected with the Zorro story. Clearly, we’re not aiming for historical accuracy, since Zorro is a fictional character. Yet, we felt it made the story richer to tap into the many cultural strains that have gone into the creation of Zorro.” For instance, Campbell says, “the head of Joaquin Murieta in the jar. We found from several sources that Murieta was killed by a ranger named Captain Love and his head was kept in a jar. We borrowed the head-in-a-jar for The Mask of Zorro and decided to call our villain Captain Love in tribute to Joaquin’s slayer.” (A long-cherished California tradition has Murieta’s head and the hand of his accomplice, Three Fingered Jack, preserved in jars for more than half a century until they were lost in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906.)

A New Zealand native, Campbell, best known for the James Bond film, Golden Eye, was actually the third director attached to The Mask of Zorro after Steven Spielberg and Robert Rodriguez had to bow out because of prior commitments. (Spielberg stayed on as one of the film’s executive producers.) “I was thrilled to have the opportunity,” Campbell says. “I grew up with the Zorro films and TV show. I must say that I think the Tyrone Power film to be a bit overrated, and in The Mask of Zorro, I wanted to take things back to the dash and athleticism of the Fairbanks original. To that end, we brought on Bob Anderson to do the choreography and Gary Powell to be stunt coordinator. I think they brought a great deal of panache to the production.”

The action sequences in both The Mask of Zorro and The Legend of Zorro buck the current trend towards special effects-enhanced fight sequences that have been fashionable in Eastern and Western cinema since Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. “I have nothing at all against that style of action,” Campbell says, “but I love to see the natural motion of the human body. I like to have the viewer watch something knowing that it’s possible for a human being to do that because they just saw a human being do it.”

Like Campbell’s first Zorro film, Legend was shot in Mexico. “We were lucky for the first film,” he recalls. “The location for the opening execution scene in the courtyard was so perfect that I thought ‘Why hasn’t someone used this in a movie before?’ I didn’t find out until later that someone had used it before—after we completed production I found out that Sergei Eisenstein had come over to Mexico from Russia in 1931 and shot much of Que Viva Mexico there. I’m afraid I didn’t show proper reverence to the fact that I was shooting on the same spot where one of the greatest directors in movie history had previously worked.”

The Legend of Zorro was shot at a new site, a hacienda about four hours north of Mexico City. “It was perfect,” Campbell says. “More lovely than any movie set could have been. We scarcely had a single travel day; almost the entire movie was shot in the area.” Campbell is reluctant to give away much of the plot, but he insists The Legend of Zorro “takes the character in a completely new direction from anything you’ve seen before. Zorro’s world has changed, and he must now deal with issues such as statehood that were undreamt of when he was a boy.” Banderas sees Zorro as a figure of nobility in an age of increasing technology. “He insists on sticking with the sword as his primary weapon and disdains the gun, the revolver, which is such an impersonal Anglo-Saxon weapon.”

This time around, Zorro must not only deal with his adversaries but contend with the problem of being Zorro and still maintain his family. His wife has become increasingly disenchanted with his spending so much time away from home. “Of course,” Campbell says, “since his wife is played by Catherine Zeta-Jones, there’s a big inducement to stay home.” Does Catherine get to pick up a sword on this film as she did in the first?

“Oh God, yes,” Campbell replies, “she kicks ass in this one. Even more than in the first. Her character is certainly more applicable to today’s woman than a Spanish noble woman of 1850s’ California, but all period movies, no matter how they might try to convey a sense of the past, must contain anachronisms. With a bit of luck, you can reflect the glory of the past and combine it with the sensibility of the modern age. Each generation will get the Zorro it deserves.”

Allen Barra is the contributing editor for American Heritage magazine and author of Inventing Wyatt Earp, currently in its fifth printing. His latest book is The Last Coach: A Life of Paul “Bear” Bryant.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Sony Pictures –

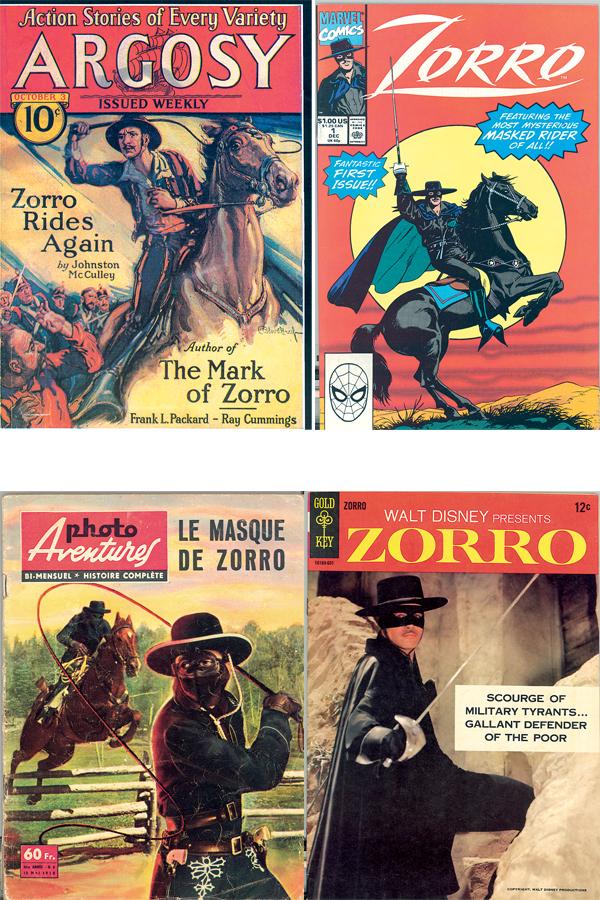

Johnston McCulley introduced Don Diego a.k.a. Zorro in the pulp zine All-Story Weekly on August 9, 1919, with the story “The Curse of Capistrano.” When the public saw Douglas Fairbanks’ silent-screen adaptation of McCulley’s creation in 1920, McCulley began writing more adventures for the masked hero, penning around 65 additional tales over 40 years. (Upon McCulley’s death in 1958, Italian editor Gialli Ponzoni introduced to the French market Photo Aventures, which printed “La Masque de Zorro,” bottom left. This is a photo-comic of the 1937 Republic film Zorro Rides Again, starring John Carroll as a singing Zorro.) The first issue of Johnston McCulley’s “Zorro Rides Again” (top left) began a four-part series in Argosy on October 3, 1931, which ended on October 24, 1931. Dell Comics produced the first comic books featuring Zorro in 1949, with 15 issues featuring art by Alex Toth. Gold Key then produced nine issues featuring Zorro in 1966 (bottom right), modeled after Guy Williams’ Zorro for Walt Disney. Marvel issued its Zorro series in 1990 (top right) but lasted only 12 issues.

– All photos courtesy Paul Hutton unless otherwise noted; Banderas photo courtesy Sony Pictures –