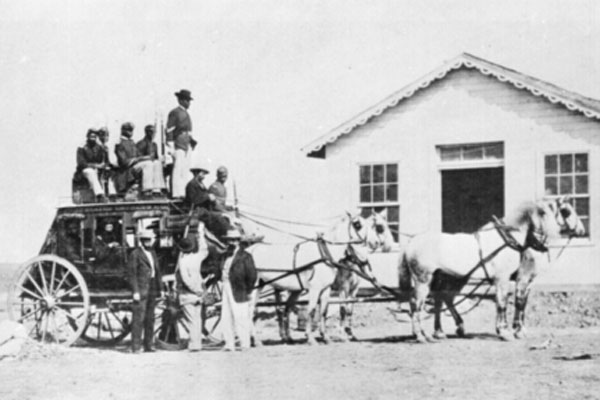

One of the iconic symbols of the old west is the stagecoach, and here’s betting there has never been a western movie without one making an appearance. It always looks so romantic, and if it’s delivering a new lady to town, she arrives all fresh and sweet, every hair in place, every pleat in her floor-length skirt as crisp as newly ironed.

Reality was a very different picture. “Stage journeys were expensive, nightmarish marathons over primitive boulder-strewn trails, up and down perilously steep grades, through swollen rivers or across them on flimsy grades,” according to “Arizona Memories” edited by Anne Hodges Morgan and Rennard Strickland.

This anthology is a collection of 28 essays and memoirs written from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s by people who lived Arizona history. The 1878 essay by E. Conklin entitled “A Stagecoach Robbery in the Desert” is very insightful.

The editors preface the memoir with a dose of reality on stagecoaches. For instance, the small coaches were meant for nine people—only doable if folks locked knees. More than nine—passengers perched on the roof or “held on for their lives.”

Food along the way was “poor,” the editors say, generously, and then share this delicious tidbit of old west trivia: “The experienced traveler carried mustard to mask the taste of the mule meat which sometimes was substituted for jerky or venison.”

And then there’s this: “The physical discomforts of a stage journey were bad enough, with sleepless nights in a crowded coach with no shock absorbers. But the abuse to the nostrils must have been worse in the era of desert travel prior to deodorants, mouthwashes, and tourist accommodations with showers.”

After all that, robberies occurred now and then, like the one reporter E. Conklin experienced.

This midnight robbery turned out OK. The two men who robbed his stage outside Florence, Arizona, got all $15 Conklin owned and the Wells Fargo box—all the while pointing rifles at him and the driver. But nobody got shot and as they resumed the trip, the robbers yelled after them, “Good night!”

Conklin writes that he was so taken aback by the polite exit, he thought for a second that they should turn around and inquire if the robbers would give everything back. But the driver told him he was nuts and they carried on. But it led him to nickname robbers “spirits of the desert.”

Once in Florence, the eastern reporter found two prospectors–Capt. Charles McMillen and Josiah Flournoy–sympathetic to his penniless plight. “Each put his hand in his pocket and passed carelessly over to me a twenty-dollar gold piece, telling me they guessed that would see me through to Yuma, and the twenty dollars would be as good to them at some other time. When I offered to give them ‘my note’, they looked displeased that human nature had fallen so low that a piece of paper was worth more than a man’s honor, and said: ‘A man’s word is his note in this country, my friend’.”