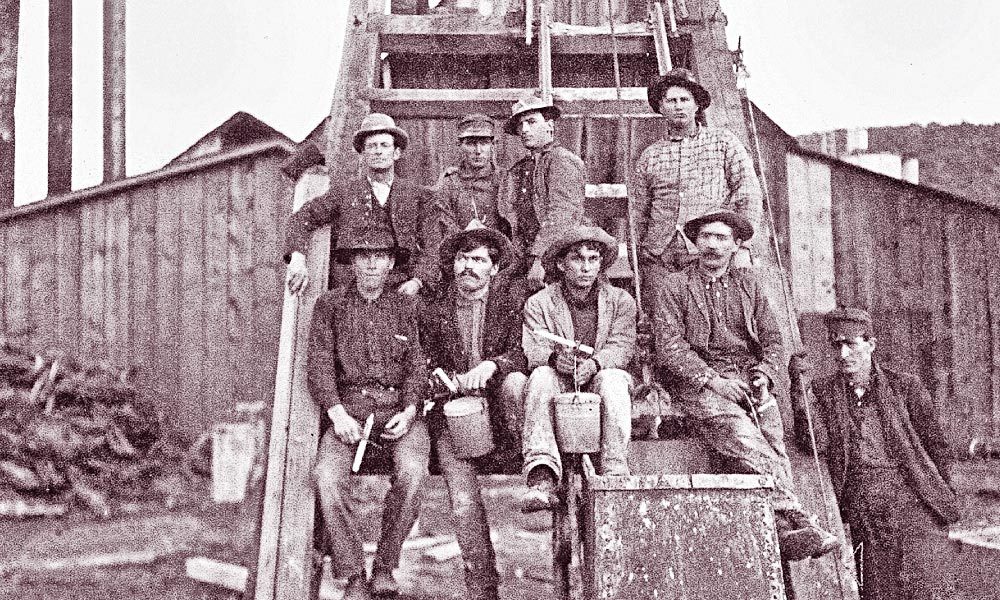

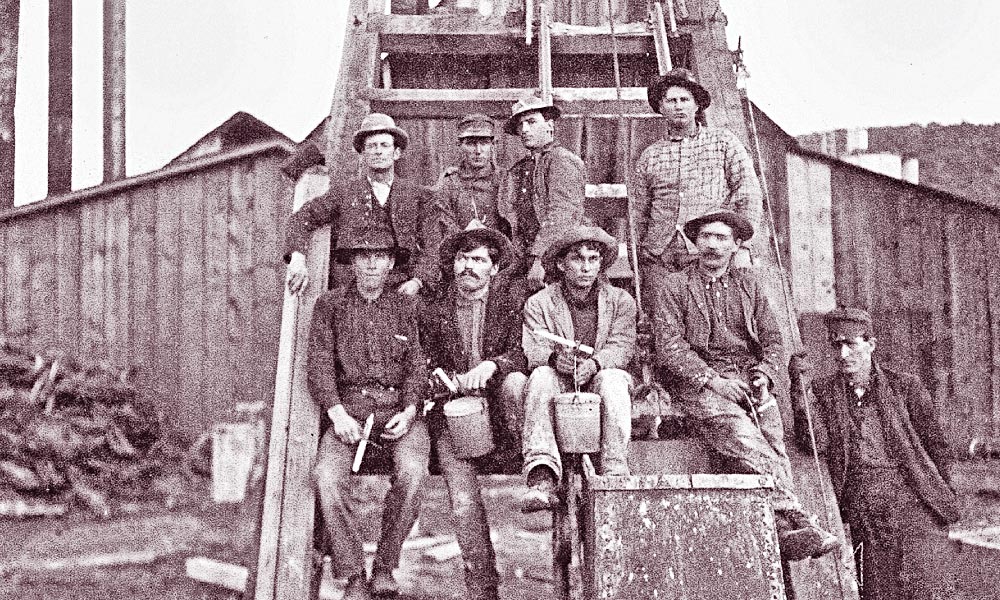

– Courtesy Gila County Historical Museum –

Author Mike Anderson prefers talking about the legends who played at Warren Ballpark in Bisbee, Arizona—Connie Mack, Honus Wagner, Jim Thorpe and others—but America’s oldest multisport facility (it opened in 1909) hasn’t always been used for baseball.

A century ago—in July 1917—Warren Ballpark became a detention center after vigilantes rounded up 1,500 striking copper miners and began the infamous Bisbee Deportation. The more than 1,100 miners who refused to return to work were forced at gunpoint into cattle cars and sent into the desert, and were eventually unloaded near Hermanas, New Mexico.

“No search warrant,” Anderson says. “No court order. No trial. No legal process.”

This history of copper mining in New Mexico and Arizona isn’t always pleasant, but it’s definitely rich.

New Mexico

Start in Hurley, the so-called “Gateway to Copper Country” in western New Mexico.

Hurley didn’t begin until 1910 after Massachusetts-born John Murchison Sully formed the Chino Copper Company and brought open-pit mining to the territory.

The mining company built the entire town. The Chino Pit, still open for view, wound up being 1,500 feet deep and 1.5 miles across, one of the world’s largest open pits near Santa Clara.

This area of Hurley-Bayard-Santa Clara, however, was rich long before Sully arrived.

In 1799, an Apache Indian showed a Spanish soldier named Jose Carrasco a copper deposit. Carrasco found Francisco Manuel Elguea, an entrepreneur from Chihuahua, who helped petition Spain for a land grant. A fort was erected in 1804 to protect the miners from Indians. Carrasco sold out to Elguea in 1804, after the Spanish had created Santa Rita del Cobre. Local historian Terry Humble writes, “It has been said that the metal in almost all of the copper coins minted in Spain and Mexico between 1800 and 1840 originated in Santa Rita.”

You won’t find Santa Rita—just a historical marker in Santa Clara. As the Chino Pit expanded, Santa Rita disappeared. Santa Clara (it became Central City, then just Central) got its start when Fort Bayard was established 1866. Before the fort closed at the turn of the century, Bayard had been home to Gens. George Crook and John J. Pershing, and Medal of Honor recipient, Cpl. Clinton Greaves. Who’s Greaves? He was serving in the 9th Cavalry in the Florida Mountains on January 24, 1877, when, according to his official citation, “…While part of a small detachment to persuade a band of renegade Apache Indians to surrender, his group was surrounded. Cpl. Greaves in the center of the savage hand-to-hand fighting, managed to shoot and bash a gap through the swarming Apaches, permitting his companions to break free.” A statue of Greaves stands at the Fort Bayard historic district.

Which brings us to Silver City. Yes, there’s more than copper here. Silver, naturally, led to the founding of Silver City in the 1870s, which brought Billy the Kid’s mother, and Billy, too, to town. But the city grew to become the capital of the copper district, and the Silver City and the Western New Mexico University museums are excellent places to learn the area’s diverse history. But keep this in mind: That log cabin next to the visitor’s center isn’t Billy the Kid’s boyhood home. It’s a set from The Missing, a lousy Western with nothing to do with Silver City, Billy the Kid or copper.Copper has taken a dive in recent years, but this district offers a wealth for history-lovers.

As author Bob Alexander writes in Six-Guns and Single-Jacks: A History of Silver City: “Silver City got short shrift in the Western annals devoted to frontier hot spots. Silver City and her outlying suburbs were a quintessential model for all that a first-class Western town had to offer—good and bad.”

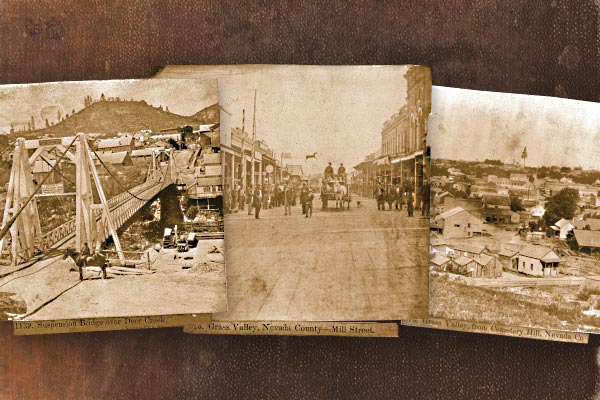

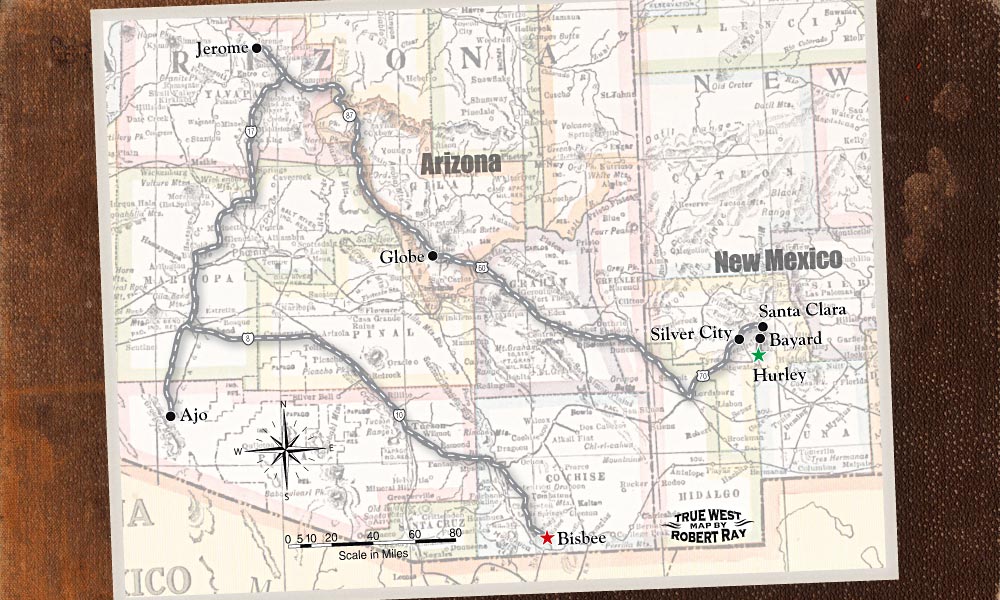

– Map by Robert Ray –

Arizona

Arizona also has a shining history regarding copper. Take Globe, for instance.

“Arizona’s copper industry became an economic force in the 1870s as mining gained prominence in the post-Civil War economy of the Southwest,” Phylis Cancilla Martinelli writes in Undermining Race: Ethnic Identities in Arizona Copper Camps, 1880-1920. “Arizona Territory was destined to be a bright star in the western constellation of copper camps after obstructions to mining ventures were resolved.”

Those obstructions were Indians, of course, and a lack of water. Miners began staking claims in the Pinal Mountains as early as 1870, but Globe wasn’t established until the Apaches had been driven out around 1876.

Globe started as a silver town but quickly discovered copper more profitable. Still a mining town, Globe also offers plenty for history buffs, including Besh-Ba-Gowah Archaeological Park, a 700-year-old Salado Culture pueblo; and the Gila County Historical Museum.

Globe’s sister cities, Miami and Claypool, also experienced the copper rush, drawing miners in the 1880s and seeing an even larger rush in the early 1900s. Check out Bullion Plaza Cultural Center and Museum in Miami and mounds and mounds of copper tailings.

The coolest of Arizona’s copper towns might be Jerome, practically a mile high atop Cleopatra Hill. Jerome began as a tent city when copper was discovered in 1876, but grew into the territory’s fourth-largest city.

Jerome “has found foothold on a mountain side, 2000 feet above the valley of the Verde, and not even a burro can climb the hill except by the ‘switch back’ method,” journalist Paul Hull wrote in 1899. “From its dizzy height is presented a scene of splendid solitude—of magnificent loneliness.”

It hasn’t changed much today.

By the 1920s, Jerome boasted 15,000 people (although I don’t know how they all fit there).

Phelps Dodge shut down its mine in 1953, but Jerome found new life as a tourist-arts town. Check out the Jerome Historical Society Mine Museum, Gold King Mine and Ghost Town, and Douglas Mansion State Park.

Down south, Ajo is among the Southwest’s oldest copper towns.

– A. Miller, Courtesy Library of Congress –

Although Spaniards mined here as early as 1750, the copper strikes really began in the late 1840s. Still, it took the Southern Pacific Railroad’s arrival at Gila Bend in 1879 and the coming of electric power (thus, a need for copper wires) to lead to better copper-mining ventures. Even then, only roughly 1.7 million pounds of copper were hauled out a year from the 1880s till 1917. From World War I until the Great Depression, copper mining exploded, and Ajo boomed. But copper prices are fickle, and the last mine closed in 1984. Today, Ajo has bright spots such as St. Catherine’s Indian School (now home to the Ajo Historical Society Museum), a scenic loop and its Spanish Colonial Revival style plaza, built in 1917. And it’s on the way to the amazing Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, just 30 miles south.

A similar story can be found in Bisbee, which survived after the copper collapse as a tourist-arts-Wild West town.

Bisbee boasted a population of more than 20,000 in its heyday. It was home to Arizona’s first golf course (Turquoise Valley) and Arizona’s first community library (Copper Queen). It was also home to Brewery Gulch, with some 50 saloons and assorted brothels. Many saloons are still there, but no brothels.

The library and golf course are still there, too. And, of course, so is Warren Ballpark, with all its history.

Copper, after all, brought baseball to Bisbee. Oh, the game was played long before, but when the suburb of Warren was laid out in 1906, a piece of level ground was reserved for a baseball field. Warren Ballpark went up, at a cost of $3,600, and a streetcar line was built to link the suburb (and its park) with Bisbee and other communities.

The strikers of 1917, by the way, did not get to take the streetcar.

Warren Ballpark wasn’t just for baseball—or a prison camp for striking workers. English immigrants played rugby there, and cricket, and even soccer. Circuses, rodeos and Wild West shows were staged there.

“This place,” Anderson says, “is a real field of dreams.”

Like most of the Southwest’s copper towns.

Because he’ll believe anything, Johnny D. Boggs wears a copper bracelet to prevent carpal tunnel when he types.