– Rick Collins –

Texans take great pride in their storied past, which is as wide and as deep as the vast Lone Star State itself. Nowhere is a sense of bygone days more evident than the legion of roadside markers that bristle like bayonets in nearly every hamlet and byway of this history-rich land.

Military sites especially abound. They are so numerous that volumes could not capture the full tale of soldiers, their families and the enemies encountered by a succession of forces from Spain, Mexico, the Republic of Texas and the United States. Indeed, for generations, fierce frontier military men galloped out on horseback or marched, fought and sometimes died in this rugged region north of the Rio Grande.

The story began as early as the 18th century when the Spanish dispatched a vanguard of lance-wielding soldados, padres, prospectors and other civilians to today’s Texas. One example of the efforts to conquer and colonize this remote area appeared along the San Sabá River. In 1757 a new fortified settlement arose which eventually would be named after the river that flowed outside the walls. During its heyday the San Sabá was a stone presidio, as the Spanish called their forts, measuring nearly 348 by 324 feet with towers on the northwest and southwest to bolster the defenses against the Lipan Apaches who had made their homes in the vicinity before the Spanish appeared. The short-lived colony came to its end during early 1768.

Eventually Spanish rule would be replaced by Mexican authority, but troops from that republic similarly hauled down their tri-color that in due course would be supplanted by the Stars and Stripes. One of the first bastions to fly Old Glory, Fort Bliss (founded in 1849 as Camp Concordia or aka the Fort at El Paso), has been a fixture on the border for nearly 170 years. Established after the United States secured staggering new territorial gains in the wake of the war with Mexico and the subsequent end of hostilities negotiated as the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Fort Bliss’s original mission was to keep order in the vicinity. Further, this assignment involved protection of hopeful emigrants trudging to California as they headed westward to link up with a trail blazed in part by army Lt. Col. Philip St. Cooke and his Mormon Battalion as part of the duel between Mexico and the United States.

With fewer than 11,000 officers and men in the entire regular army of the dozen

pre-Civil War years, this thinly spread force was tasked with national defense from coast to coast and from Canada to Mexico. The military’s assignments of the 1840s and 1850s were daunting, to say the least. Over scores of years, the longtime former frontier garrison of Fort Bliss evolved into one of the most modern and largest United States Army installations in the nation. Today thousands of high tech-savvy dedicated men and women in camouflage combat-battle dress prepare and stand ready to deploy around the globe, in stark contrast to the handful of blue wool-clad frontier troopers who once garrisoned this remote outpost. Some of them found their final resting place in nearby Concordia Cemetery among nearly 60,000 people buried in this hallowed ground.

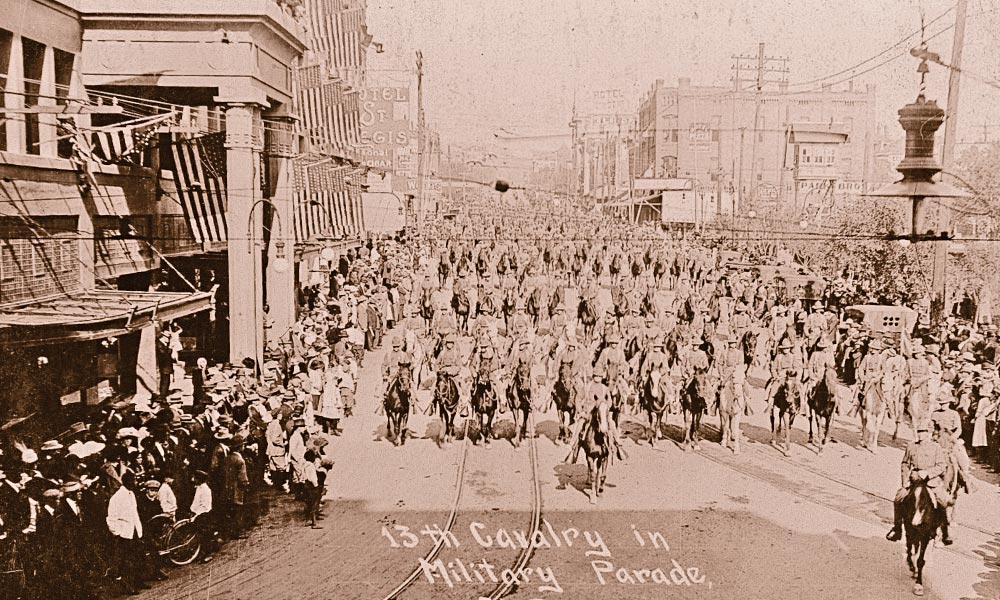

– Courtesy Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library –

Like Fort Bliss, the old El Paso-San Antonio Road was another feature of antebellum Texas. This vital route to and from California required protection that led to the establishment of a number of firebases along the way, such as the Post at the Limpia, established in 1854. Once again, this outpost assumed responsibility for settlers and travelers, some of whom bumped along as passengers on the jostling, cramped Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoaches in a locale crisscrossed by traditional Apache and Comanche raiding trails. Eventually the county in which it stood, and the fort itself, changed names, reflecting the impact of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis. His influence on the region included dispatching army exploration parties to locate the best roadways across the southwestern United States for wagon traffic and eventually the rail beds for the iron horse. Later, Davis would become better known as the president of the Confederate States of America.

After Davis’s administration collapsed the United States returned as a single nation and a contingent was dispatched to re-establish the abandoned site, albeit adjacent to the former fort. This slight shift was not the only change, however, because the post-Civil War U.S. Army differed from its previous makeup. In fact, one of the outcomes of the conflict between North and South was the abolishment of slavery along with the establishment of several regiments of cavalry and infantry that have become popularly known in modern times as the Buffalo Soldiers. Many formerly enslaved blacks joined by freedmen made up the rank and file. Some of these blacks in army blue had served during the war. Many others were new to the military, which was the case for the three African American officers who received commissions during the 1870s and 1880s (all other officers were white, based on racial stereotypes of the era). The first to earn this distinction, Henry O. Flipper, graduated from the United States Military Academy’s Class of 1877. Assigned to the 10th U.S. Cavalry, one of the two regiments of African American horse soldiers, Flipper reported to Fort Davis where he earned his spurs during the campaign against the capable, illusive Apache leader, Victorio.

Regrettably, the young shavetail’s military career proved short-lived. He would be brought up on charges of conduct unbecoming an officer and other allegations of wrongdoing. Placed in the Fort Davis guardhouse, despite the custom that officers were to be held under house arrest, Flipper faced his court martial in the post chapel pressed into service as a courtroom. A verdict of guilty resulted in the end of his career with a dishonorable discharge from the army. For the remainder of his life the disgraced lieutenant attempted unsuccessfully to regain his commission.

Fort Stockton, another way station for those heading to the West Coast from San Antonio, began in 1858. Within three years federal troops would abandon the camp. In 1861, soon after the outbreak of war with the South, a small Confederate contingent took temporary possession of the vacated facilities. Once more, the newest occupants of the garrison likewise withdrew, leaving behind rapidly deteriorating buildings.

Then, during July of 1867, black cavalrymen reported to build a new post under Col. Edward Hatch, regimental commander of the 9th U.S. Cavalry. Hatch would remain in command of this outfit for over two decades. Several of his subordinates also continued with the unit that called Texas home for many years before moving on to New Mexico Territory and other assignments. Whether staffed by black or white soldiers, the military mission helped fuel local economic growth. Troops needed food, firewood and other necessities that gave rise to booming business for merchants, cattlemen, farmers, freighters and others until the bubble burst with the post’s abandonment in 1886.

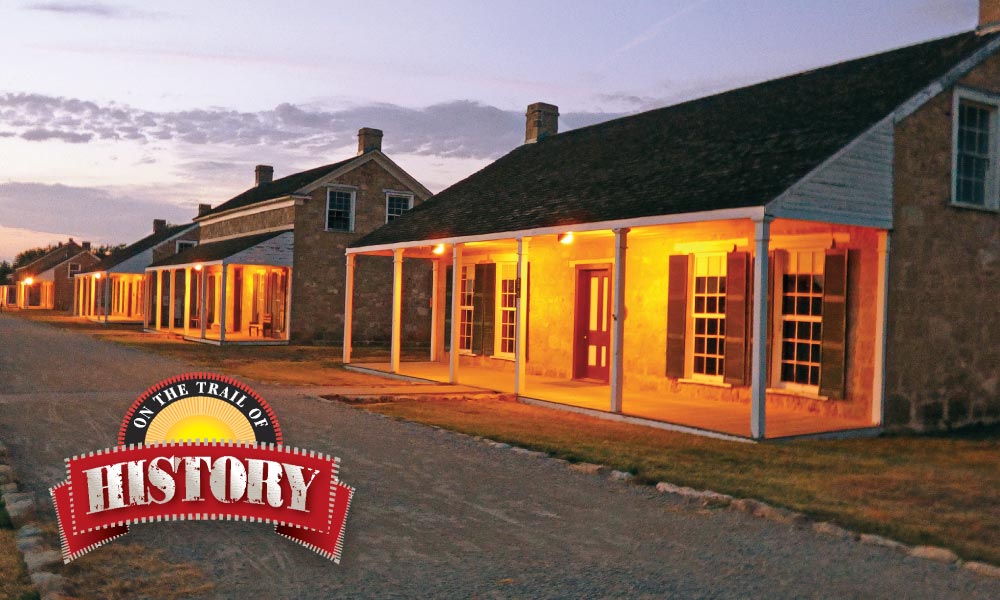

Another 1867 addition to the chain of Texas post-war forts was dubbed Camp Hatch after the 4th U.S. Cavalry officer Maj. John Porter Hatch who dispatched troopers to the confluence of the Main and Concho rivers. Hatch, a recipient of the Medal of Honor for heroic actions during the 1862 Battle of South Mountain, Maryland, evidently felt it inappropriate for the place to carry his name, so in 1868 he recommended Camp Kelly as a more appropriate title, for a comrade, Capt. Michael J. Kelly, who had died of typhoid fever—a not uncommon scourge for the military and civilian populace during the period. Eventually that name gave way to one that tied the post to its locale—Fort Concho.

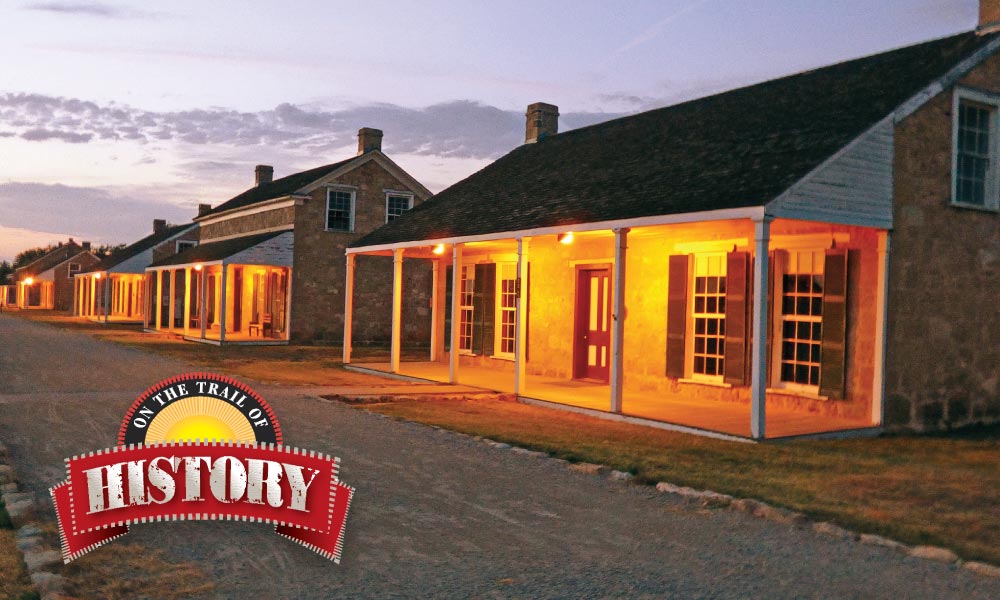

– The Lyda Hill Texas Collection of Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division –

Another Buffalo Soldier regiment, the 10th United States Cavalry under Col. Benjamin Grierson a former music teacher-turned-cavalry commander, rode onto the scene. After Grierson’s arrival, he and his successors saw to it that the post grew considerably through the late 1880s. Many large imposing stone structures would sprawl around the parade ground and beyond, forming an impressive martial community dedicated to maintaining calm in the area and once again priming the coffers for those who supplied the fort’s residents both in garrison and in the field. In the latter instance, patrols launched against the Apache, Comanche, Kiowa and other tenacious Texas tribesmen more than once ran out of their precious food and water while hunting highly mobile, formidable foes. The Lords of the Plains, as the Comanches had been called by some understandably impressed white adversaries, especially ranged far and wide, sometimes seeking sanctuary in the Llano Estacado (“Staked Plains”), where almost certain death faced those entering this godforsaken, barren wasteland.

Outlaw and revolutionary elements likewise loomed large, the former group including the comancheros as arguably the worst of a bad lot! Added to this, the diplomatic complexities of international relations further presented obstacles. In the 1860s European powers had dispatched occupation forces for a time in an effort to establish a puppet government in Mexico propped up by the French. This foreign presence threatened hostilities. Then, too, after the French abandoned their imperialistic adventure, the reconstituted Republic of Mexico frowned on crossings of the international line by Americans, even when hot on the trail of war parties and bandits seeking refuge across the border. But there were those who with equal determination sought to bring a tenacious array of rampaging raiders to bay. Among them, Col. Ranald S. MacKenzie might be considered the true unsung hero of the legions who followed the Guidon in Texas.

Last year John Langellier “field-tested” this travelogue with photographer Rick Collins as part of his Border to Border Buffalo Soldier Book Tour, promoted by True West magazine.