On a chilly October afternoon in 1881, a misdemeanor arrest in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, escalated out of control in a matter of moments. Thirty seconds and 30 bullets later, three of four sworn officers were wounded. Of five civilians, three were dead, and one of them was unarmed.

Within hours, the AP wire service made the “gunfight at the O.K. Corral” news around the world. To this day, the names of the participants are remembered and controversy about the event remains lively. What was the fight really about? Whose fault was it?

Legal and moral ambiguity has made the story compelling to hundreds of writers, myself among them. I suspect, however, that most of us are drawn into the history because of Doc Holliday.

In life, he had few friends, but in American mythology Doc has become clever Odysseus to Wyatt Earp’s stalwart Achilles—a source of detached amusement and witty commentary. Wyatt’s the hero, but Doc is the one we love.

There are many versions of the tale. Usually a gambler and gunman called Doc Holliday arrives in Tombstone with a bad reputation and a hooker named “Big Nose” Kate. The character is dying of TB, so he is careless of his own life, a quick death being preferable to what tuberculosis threatens.

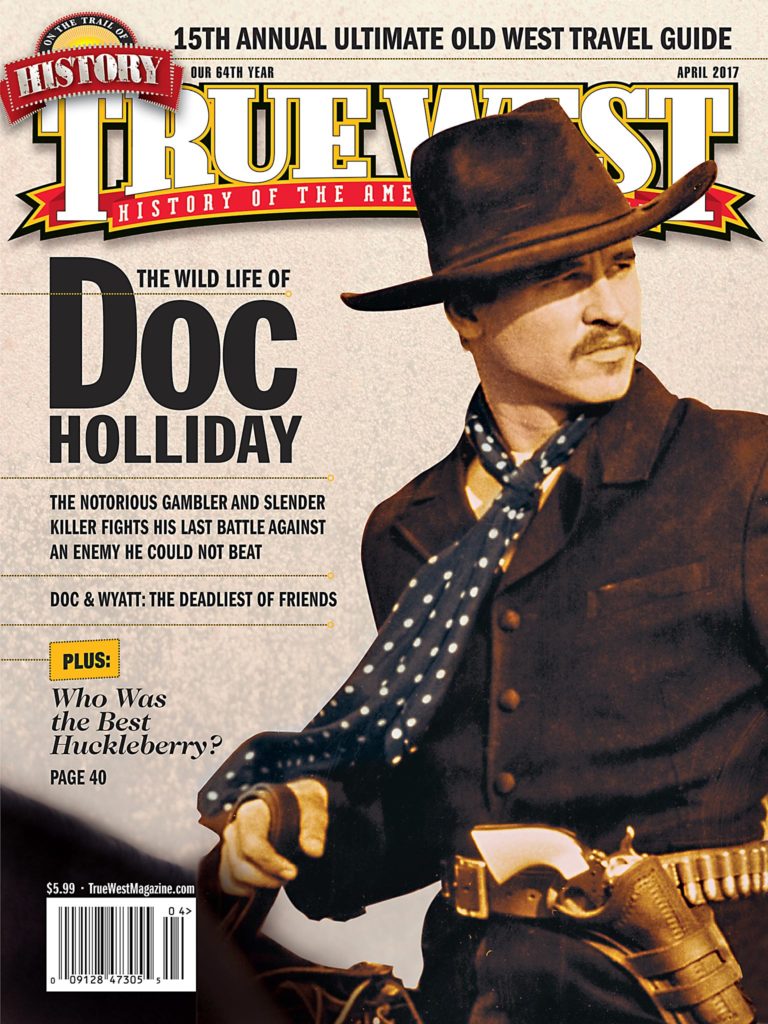

Some fine actors have been cast as Doc, and they all brought something memorable to the role. In 1967’s Hour of the Gun, Jason Robards was sarcastic and funny, though too old to play a man who died at 36. In a 1971 film, “Doc,” a young Stacy Keach made us listen to the appalling, violent cough of late-stage TB, making us feel how ugly and painful the disease is.

Dennis Quaid lost 30 pounds to play the tubercular dentist for 1994’s Wyatt Earp. The screenplay gave him awful dialogue, but when you see Quaid stalking along on those broomstick legs, you get a real sense of Doc’s physical frailty.

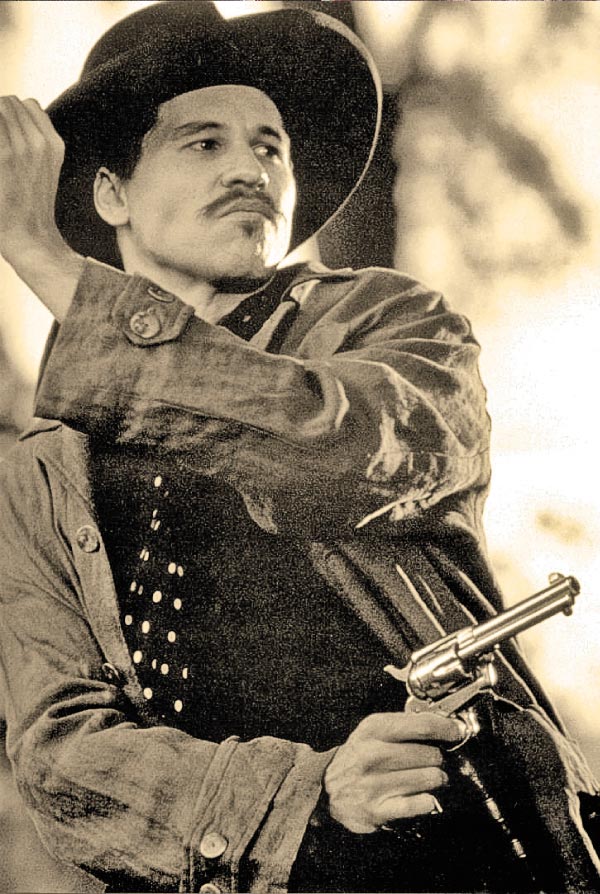

Val Kilmer’s Doc looks a little too robust by contrast. And yet, in my opinion, nobody captured the real Doc Holliday as well as Kilmer did in the 1993 classic Tombstone.

– All Tombstone photos Courtesy Buena Vista Pictures –

He had great material to work from: a Doc who is amusing and amused, worldly and urbane, a man who is seriously ill, but who waves off his friends’ concerns about his illness and sneers at sympathy.

Kevin Jarre’s well-researched screenplay accurately presents Doc as a consumptive Southern gentleman who speaks Latin and plays Chopin. The Holliday family was indeed privileged Georgia gentry, and Doc was, in fact, well-educated.

Throughout his short life, however, the real John Henry Holliday faced a series of medical challenges. He was born with a cleft palate and lip in 1851, when that condition commonly resulted in an infant’s death by starvation or pneumonia. His own uncle, Dr. John Stiles Holliday, surgically repaired the defect—the first time that European procedure was done in North America.

As a toddler, the child had a significant speech impediment. His mother invented speech therapy for him and started his piano lessons early, to counteract his shyness.

Ten years old when the Civil War began, the boy endured hunger and deprivation, and watched that hardship hasten his mother’s decline as tuberculosis slowly withered her to bone.

A serious scholar, he earned the degree of Doctor of Dental Surgery at the age of 20 from the best dental school in America. Just 18 months later, he himself was diagnosed with advanced pulmonary tuberculosis.

Take that, Ringo!

– Illustrated by Bob Boze Bell –

At 22, he left everyone and everything he loved, hoping that the dry air and heat of the desert Southwest would give him more time. It did, but like his mother, he died in his 30s, having been sick his entire adult life. He lost his battle at 36, living a year less than his mother had.

He was no fatalist seeking death. To the very end, he was hoping for a cure. He wanted what everyone in a hospital wants: to get better and go home.

The beauty of Kilmer’s portrayal of this man is that he briefly lets us see how scared and ill Doc is. Now and then, we enter the private life of a sick man whose dignity and pride require that he keep his distance from most people. That feels like a privilege.

Few of us will confront death as dramatically as Doc and the others did, standing six paces from armed and angry men. But all of us will die, and many of us will do so slowly.

Doc Holliday and Val Kilmer showed us how to stare at that kind of death and face it down with humor and bravura and gallantry. We are grateful, and we’ll remember both of them.

Author of acclaimed novels Doc (Random House, 2011) and Epitaph (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2015), Mary Doria Russell holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology; she taught head and neck anatomy at the Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine.