– All Photos Courtesy NevadaTourism Unless Otherwise Noted –

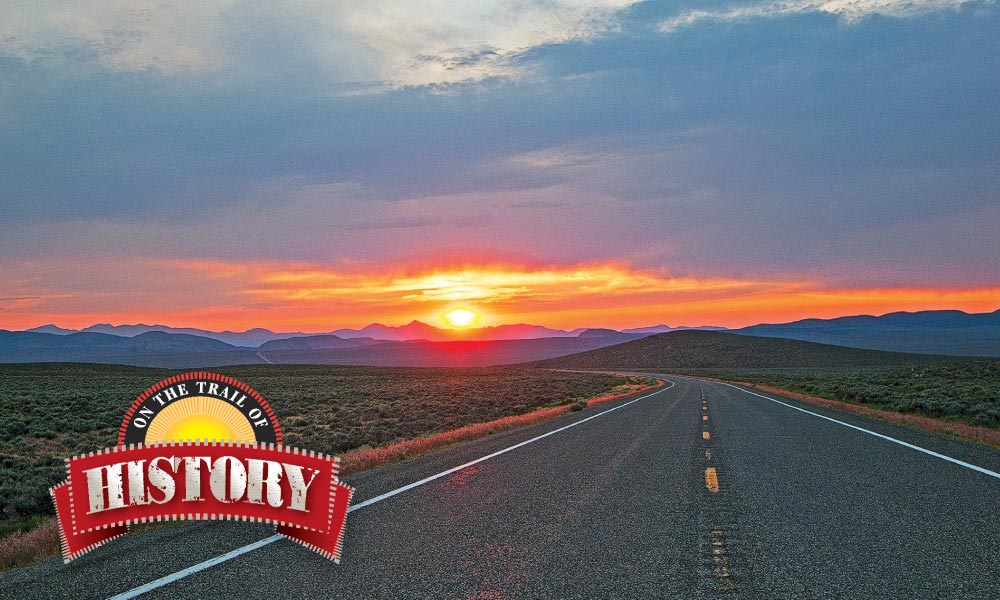

With its turquoise skies, billowing thunderheads, wide deserts and blue mountains, Central Nevada is right out of a Maynard Dixon landscape. Cresting a desert ridge to see another wide Great Basin valley and thirty miles of open highway running straight and empty to the next range, is one of the highest highpoints of driving the West’s back roads. Highway 50 approximates the Pony Express and Overland Stage road trail across Nevada. From Ely west to beyond Fallon, it’s also the Lincoln Highway, America’s first transcontinental road.

For anyone seeking disappearing history, adventure, good folks and great scenery, there’s no place better to look than Highway 50. Its “Loneliest Road in America” nickname is so worn out it could use a new one—how about the best scenic road to real Western history? Or the best place to revisit 1956?

Over the 406 miles between the Utah border at Baker to Stateline on Lake Tahoe, this two-lane highway crosses the 1827 trail of path-finding mountain man Jedediah Smith, John C. Fremont’s 1845 wandering trail to Walker Lake, and the route topographical engineer James Simpson explored for the U.S. Army in 1859, following the trail George Chorpenning had opened up in 1858 for his California Mail Company—aka the Jackass Mail.

Baker, Nevada, and Great Basin National Park are a great place to start. (Know those classic clips of wagon trains fording rivers or parting ways for Oregon or California?

They’re from The Covered Wagon, filmed in 1922 at Otto Meek’s Baker Ranch.) At 13,065 feet, glacier-clad Wheeler Peak is the highest point in the park and once home to Prometheus, a bristlecone pine at least 4,862 years old—perhaps the old living life on earth—before researchers cut him down in 1964. Ooops.

The park’s Lehman Caves are a subterranean wonderland of limestone speleothems, stalactites, stalagmites and ancient American red hematite pictographs. (There would be more, but after Ab Lehman discovered the caverns in 1885, he told early tourists “if you can break it, you can take it.”) The caves’ Grand Palace, Music Room and Lodge Room have done double duty as speakeasies, fallout shelters, bandstands and dancehalls but still amaze 100,000 annual visitors.

Highway 50 connects the mining towns of Ely, Ruth, McGill, Eureka and Austin, passing steam trains, opera houses, petroglyphs and turquoise mines to the Naval Air Station at Fallon, where the highway adds two lanes and turns south to Carson City.

For fifteen years its six stories made Ely’s 1929 Nevada Hotel the state’s tallest building. Its 67 rooms (named after folks such as Jimmy Stewart and hometown girl Pat Nixon), casino, and always-open restaurant make it a fantastic place to play and stay.

The busted boomtowns at Eureka and Austin are mining history gems. Eureka was Nevada’s second-largest town in 1878, and its fireproof Opera House, built on the smoking ruins of the Odd Fellows Hall, has served as the community’s heart since 1880. The county restored it to its original glory in 1993. This beauty and its companion Eureka Sentinel Museum, where newspaper time stopped in 1960, are both priceless.

For a great 114-mile side trip, head north from Eureka to Carlin on Nevada 278 and east on I-80 to Elko, Basque restaurant heaven and home of the Western Folklife Center. West of Elko you’ll find the Hastings Cutoff and the California Trail Center, where you too can “See the Elephant.”

West of the historic mining town of Eureka, Highway 50 crosses the Simpson Park Mountains at Hickison Petroglyph Recreation Area. Close to Nevada’s geographic center, the summit offers a great view and a half-mile walk through panels of mysterious ancient art. (You can see more desert varnish masterpieces at Grimes Point archeological site east of Fallon.)

Austin nestles at 6,605 high feet on the western slope of the Toiyabe Range. According to legend, a Pony Express pony kicked over a rock, discovered silver, and started a rush that created Austin in 1862. The next year Austin’s 10,000 miners raised a quarter million dollars for Civil War wounded. Parts of the International Hotel arrived from Virginia City. The International still serves meals and drinks, and there’s lodging across the street at the Cozy Mountain and Lincoln motels. You can soak in Spencer Hot Springs or, a thousand feet from town, check out Stokes Castle.

A mining magnate built this impressive three-story stone tower, used it for a few weeks in 1897, and never came back.

Driving west through what Mark Twain called a “majestic panorama of mountains and valleys” reinforces much of what he said about the Great Basin being “one of that species of deserts whose concentrated hideousness shames the diffused and diluted horrors of Sahara—an ‘alkali’ desert.” Driving Highway 50 shows there was no easy way to get a wagon to California. Overlanders and their animals had to face hundreds of miles of arid trails, and the trail got worse until it reached the Sierra Nevada’s rivers. Mountain men, explorers, and promoters spent a generation trying to find shortcuts.

General Albert Sidney Johnston later died at Shiloh, but in 1859 he was commander of the U.S. Army’s largest post at Camp Floyd. He reported “the successful result of Captain Simpson’s exploration for a new and more direct route.” James Simpson “believed his new route shorter by three hundred miles.” It was “excellent, and abounding in all the requirements of a good road…except for about 36 miles, which he says is bad.” Johnston assumed this meant “as compared with the other parts of the route.”

Better data changed Johnston’s mind. The route might be “of real value for military and mail purposes,” but until the country was better known, Johnston did not want Simpson trying “to turn the main tide of emigration” onto it. If the shortcut lacked sufficient grass and water, as it did, the tide could not be “checked and turned aside in time to prevent immense suffering.”

It did work as an Overland Stage road. Celebrities who rode mail wagons to California included Horace Greeley, Sir Richard Burton, and Mark Twain. The “long-headed” Mormon Danite and formidiable frontiersman Howard Egan helped Russell, Majors & Waddell’s Central Overland California & Pike’s Peak Express Company—the Pony Express—appropriate Chorpenning’s stations. “Stagecoach King” Ben Holladay bought the line when the Pony went bankrupt and sold it in 1866 to a little outfit called Wells-Fargo Express for a cool $1.5 million.

Pony Express and stage stations survive at Rock Creek and Cold Springs. After Richard Burton staggered off the stage at Sand Springs Station in October 1860, he described it as “roofless and chairless, filthy and squalid,” full of dust, with “walls open to every wind.” Burton’s “vile hole” is now a hike off the highway but is worth it, for Sand Springs is often called “the best-preserved Pony Express station” in the USA.

From Fallon, Highway 50 follows “the tracks of the Elephant”—the California Trail—across the Carson Route of the notorious Forty-Mile Desert. For Twain, this forty memorable miles of bottomless sand was “the Great American Desert,” a prodigious graveyard where rotting wagon wrecks were “almost as thick as the bones” you could step on for forty miles. The sight gave him “something of an idea of the fearful suffering and privation the early emigrants to California endured.”

Drive far enough west on 50, and the scenery looks like the Sun’s Anvil in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. You almost expect to run into camels. During the 1860s at least seven overland diarists mentioned seeing camel trains hauling supplies to mining camps. Shortly after George Harter camped at Diamond Springs north of Eureka, “two men with three dromedaries came up and camped with us. These animals frightened our mules very much,” he wrote in 1864. “These animals are used some here on the deserts and carry large burdens.” The beasts, maybe survivors of the U.S. Army’s 1857 experiment, never caught on in the West. Though often derided, camel drivers were as specialized as muleskinners. Harter nailed why the experiments failed: camels terrified the mules.

West of Fallon, 50 heads south to Eagle Valley and Nevada’s capital at Carson City. The adobe walls of Civil War relic Fort Churchill, now a state park, and the great Comstock Lode are both close by. A buck will get you into one of Virginia City’s oldest buildings, the Territorial Enterprise. Now the Mark Twain Museum, you can see the desk and chair in the basement where Sam Clemens became America’s greatest comic. Or you can share a drink with Twain’s ghost at the Bucket of Blood Saloon.

Two great steam-powered wonders—the Nevada Northern Railway at Ely and the Virginia & Truckee Railroad at Virginia City—bracket Highway 50 east and west. The Nevada Northern is open year-round (except Tuesdays, Christmas, and New Year’s Day) and isn’t bragging when it claims to be “the best-preserved example of a standard-gauge short-line left in North America,” because it’s true. The V&T runs only in summer to Gold Hill, where the doomed Grosh brothers discovered the Comstock Lode in 1857 but died. Old Virginny Finney, Big French John Bishop, and other drunks claimed the discovery and got the credit two years later.

The Nevada State Museum preserves Carson City’s U.S. Mint. Fremont’s lost howitzer and the world’s largest Columbian Mammoth are on display. If you’re from Wabuska, Nevada, you’ll find your historic station still selling tickets for original V&T rolling stock fifteen blocks south at the Nevada State Railroad Museum.

From Carson City, Highway 50 heads into the Sierra along the line of Colonel Jack “Cock-Eye” Johnson’s wagon road. The twin tunnels through Cave Rock connect Glenbrook and Zephyr Cover through De ek Wadapush (Standing Gray Rock), looming above Lake Tahoe’s south shore. You can’t linger or loiter at this sacred Washoe site, but it’s a good spot to end this trek and tale.

Will Bagley’s two dozen books have won three Spurs from Western Writers of American. He is working on The Whites Want Every Thing: Native Voices from the Mormon West, for the Arthur H. Clark Company.