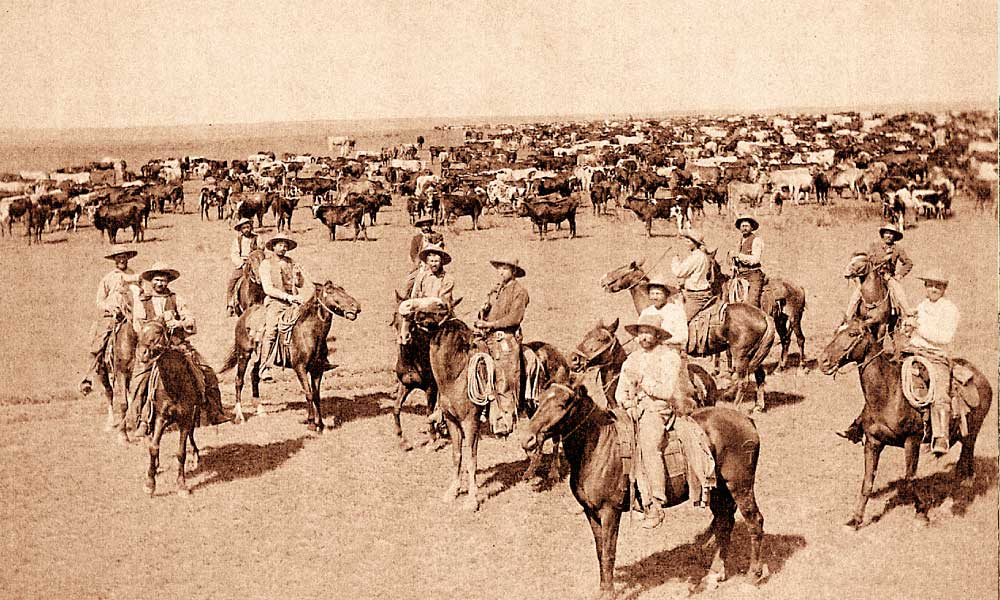

William Henry Jackson captured this iconic photograph of Texas cowboys with their herd behind them. “We always rode something like seventy-five feet away from the cattle, and sang a song or made some kind of noise,” recalled Evan G. Barnard, who became a Cherokee Strip cowpuncher in 1882. “That was done so that the cattle would not be frightened if we happened to have to ride near them suddenly. If they heard us singing or humming a tune, they knew what was coming. Also the noise we made kept the coyotes away from the herd. They often prowled around and scared the cows that had calves.”

–Courtesy Library of Congress –

Rise of the Cowboy

Before the Mexican-American War concluded in 1848, American traders who traveled to the Western frontier encountered Spanish vaqueros of northern Mexico. The arrival of railroads and an increased demand for beef during the Civil War drove the need for the cowboy. The earliest known photographs of these iconic Americans are tintypes, taken as early as the 1870s, most likely captured during a trail drive or at an end-of-trail town.

The Texas Live Stock Journal wrote glowingly of the cowboy on October 21, 1882: “A man wanting in courage would be as much out of place in a cow-camp, as a fish would be on dry land.

Indeed the life he is daily compelled to lead calls for the existence of the highest degree of cool calculating courage…the cowboy is as chivalrous as the famed knights of old.”

John Baumann, a British immigrant who moved to Texas and lived with the cowboy “on his lonesome prairies,” warned of obscuring the true character of these men with romantic qualities. In “On a Western Ranche” published in The Fortnightly Review on April 1, 1887, he cautioned the “restless, roving spirits who may be attracted by picturesque descriptions of a cowboy’s life that, unless they are prepared to toil during the long summer months, both by day and by night, for small pay and on scant fare, to be in the saddle from early dawn until sunset both Sundays and week-days, to abstain from comfort and civilisation for the greater part of every year, and so as to wear themselves out with exposure and manifold fatigues as to be reckoned old and past their work whilst still young in years, they had better remain at home and leave cowboy life alone.”

Baumann found journalism better suited him. He had been employed by a Panhandle cattle ranch four years earlier, working among the cowboys who painfully drove away half-dead and terrified horses struck by the poisonous loco weed that threatened to spread death to other horses and cows.

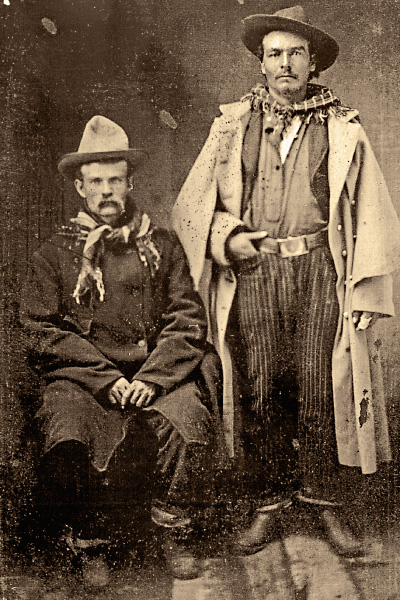

The image of another Panhandle cowboy has lasted the test of time. In an 1880s cabinet card, captioned “The Genuine Cow Boy Captured Alive,” Cottonwood Charlie Nebo stands with his “half-breed” partner Nicholas Janis, a descendant of an early-day interpreter at Wyoming’s Fort Laramie. Charlie’s daughter, Maude, captured his words in 1917: “I have been a cowboy for over 40 years. Have driven herds of cattle from the Gulf of Mexico to Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota. In one bunch we had over seven thousand steers. I have driven ‘The Staked Plains’ three or four times with big herds of cattle—96 miles without any water in some parts of the journey. Am a veteran of the Civil War and an ex-Texas Ranger. Have had some exciting times in my career.”

The man behind the camera is among the unsung heroes who preserved for posterity early-day frontier cowboys. Tintypes are rarely identified by photographers, but others entered the scene later on and made names for themselves capturing on camera the open range days up to the early 1900s. These recorders of history included Charles Belden, L.A. Huffman and Erwin Smith, the latter whom historians at the Amon Carter museum in Fort Worth have memorialized as one of the greatest photographers of cowboy life who ever lived. From the beginning, America’s pioneer image makers followed the cowboy on the ranges or in trail towns, transporting heavy cameras, tripods and wet-plate equipment, and developing their negatives in makeshift darkrooms that ranged from tents to a canvas blanket. Without them, we would have a far-sighted notion of one of the most dramatic periods of American history.

Throughout this issue, the editors bring to you the best cowboy photographs of the frontier American West. To us, each one of these cowboys epitomizes Baumann’s words: “He is in the main a loyal, long-enduring, hard-working fellow, grit to the backbone, and tough as whipcord; performing his arduous and often dangerous duties, and living his comfortless life, without a word of complaint about the many privations he has to undergo.”

—Meghan Saar

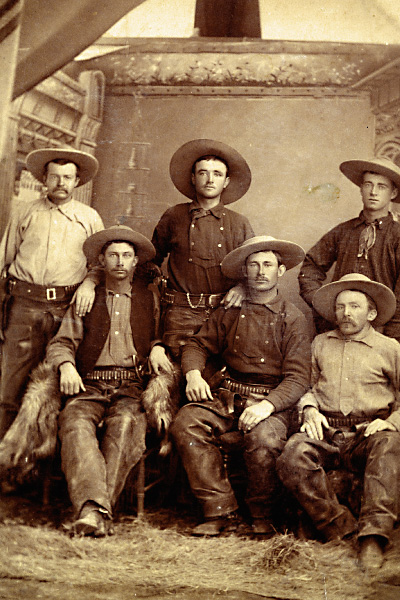

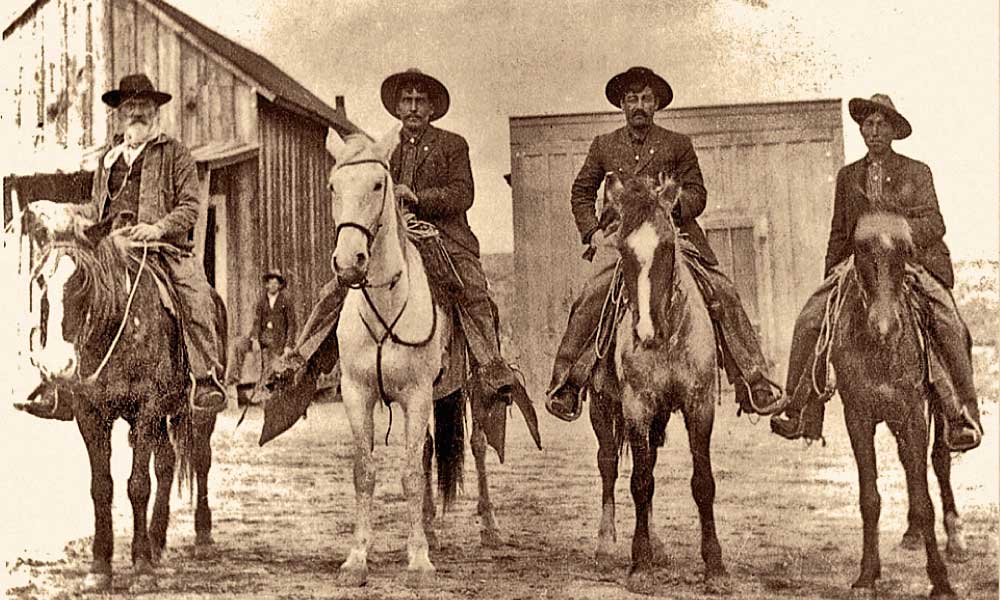

A Texas Ranger during the Civil War before becoming a cattle businessman, Texas John Slaughter opened his final ranch near Douglas, Arizona. Robert G. McCubbin, the world’s foremost Old West photo collector, says this circa 1885 cabinet card of Slaughter’s cowboys is the best group photo of real working frontier cowboys. (Top row, from left) James Pursley, Walter Fife and James G. Maxwell. (Bottom row, from left) Billy Riggs, J.H. Mclelme and Judge John Blake.

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

These cowboys in vests pose at a mid-1880s roundup on the VV Ranch, which introduced Angus cattle to the region surrounding Ruidoso, New Mexico. A wealthy whiskey distiller in Scotland, James Cree attempted to improve local longhorn stock by importing Angus bulls from his homeland to the railhead near Socorro, New Mexico.

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

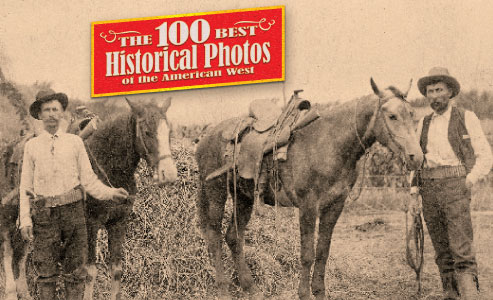

Working cowboys engaged in trailing longhorns to markets or to a new range, these drovers appear to date to the 1870s. They have not yet adopted traditional cowboy clothing and are wearing military frock coats, pinstriped pants and nondescript hats. The cowboy on the right held up his pants with a military belt and buckle.

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

Photographed in the 1890s in downtown Wickenburg, Arizona, these pioneer Hispanic vaqueros are named (from left): Jesus Olea, Francisco Macias, Juan Grijalva, Clemente Macias. Francisco is the great-grandfather of Julia Macias Brooks, the executive director of Wickenburg’s Chamber of Commerce and a fifth-generation descendant who authored a book about the town’s pioneer Hispanic families.

– Courtesy Wickenburg Chamber of Commerce –

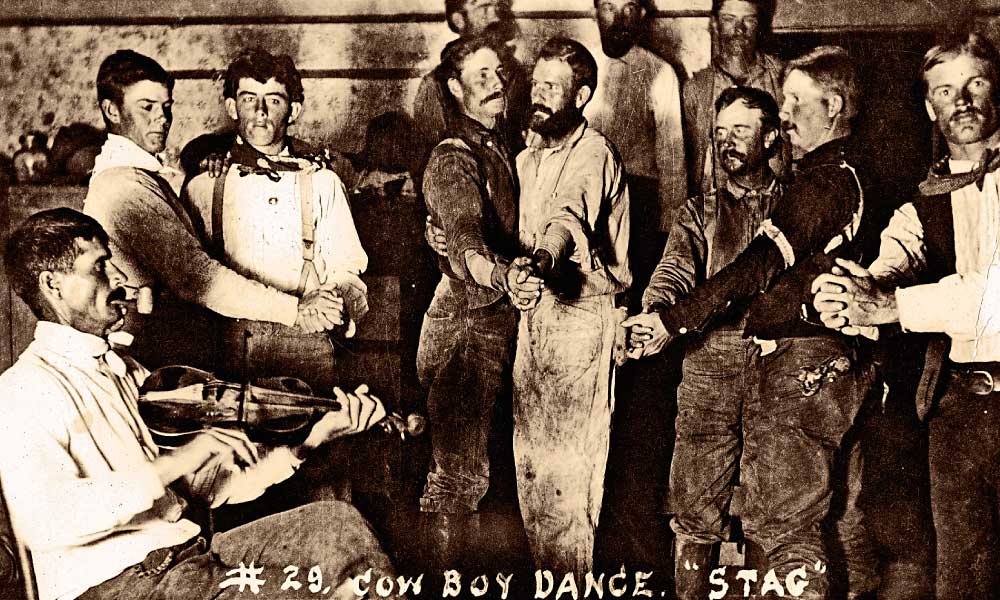

In frontier days, women were few and far between, particularly on ranches, so men would two-step and waltz with each other at dances. “Heifer branded men,” who danced the woman’s role, sometimes wore handkerchiefs tied around one arm, like the gentleman at right in the above photo. Such cowboy stag dances were mainly a source of humor and reflected good times.

– True West Archives –

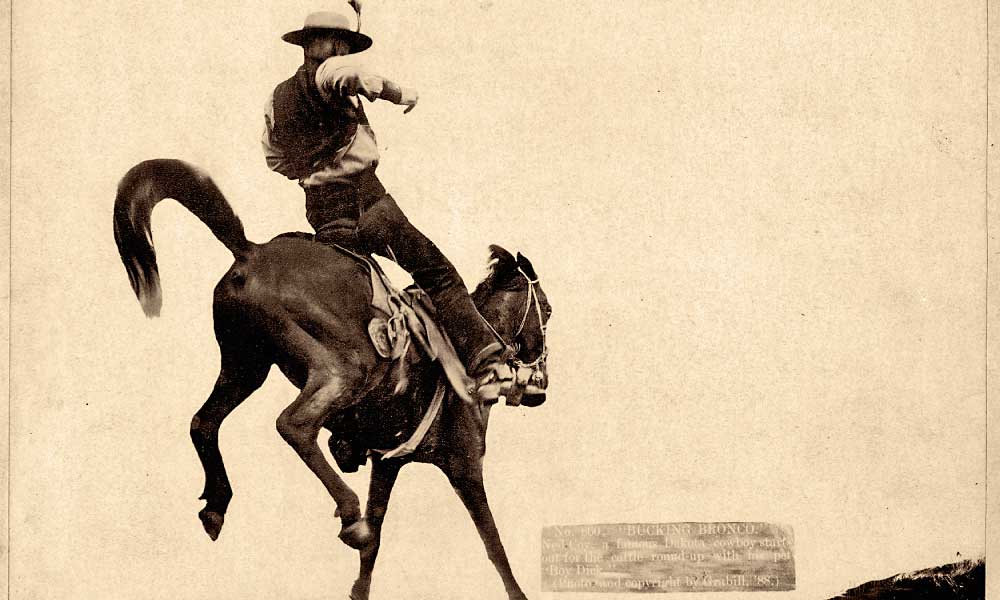

John C.H. Grabill opened his first photography studio in Sturgis, Dakota Territory, in 1886. Two years later, he photographed North Dakota cowboy Ned Coy on his bucking bronco, Boy Dick, during a cattle roundup. Not much is known about Grabill’s life before his arrival in the Black Hills nor after he left in 1892, yet his lens captured a majority of the earliest photography in the territory.

– True West Archives –