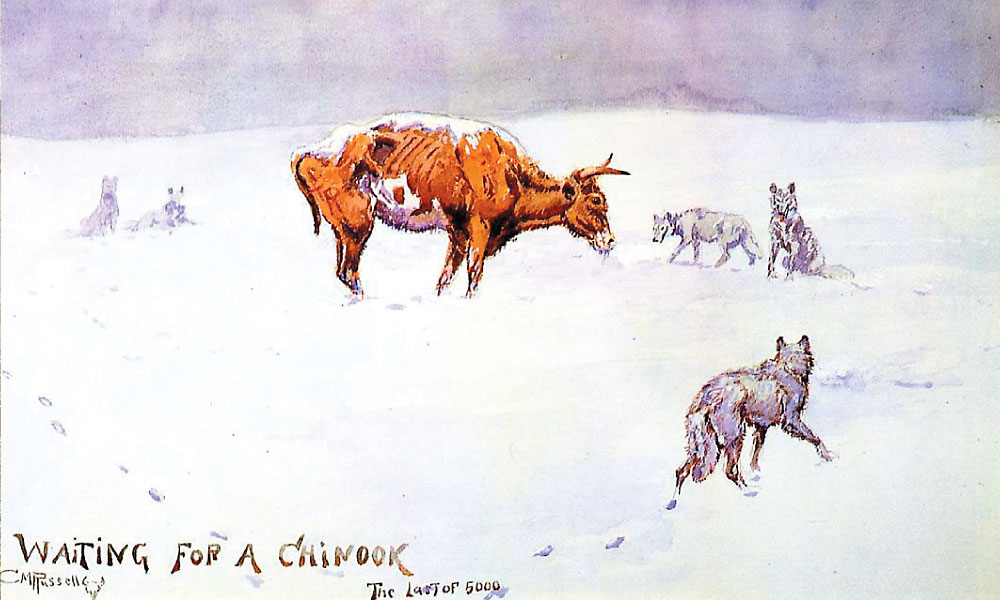

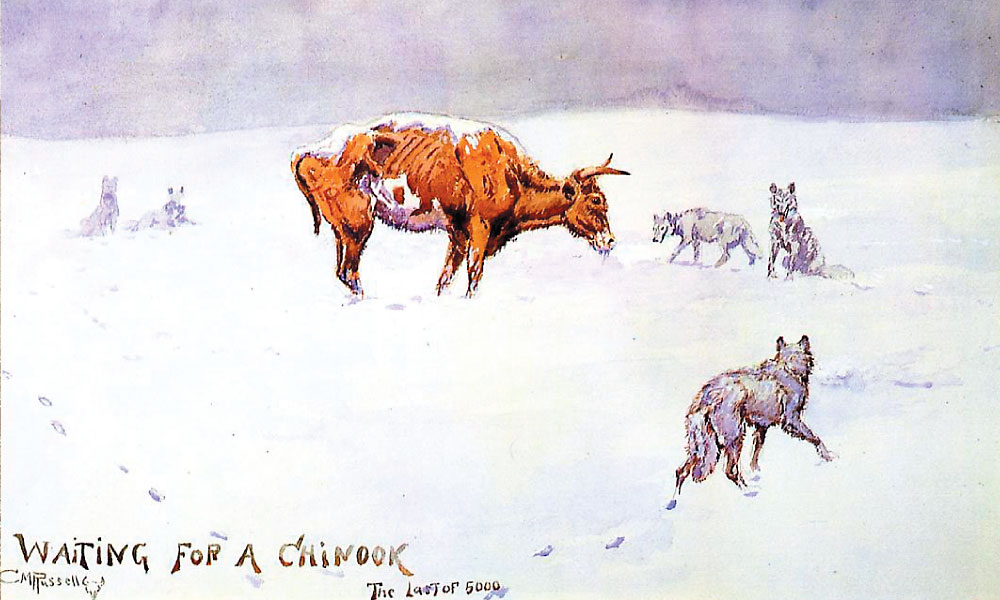

during the winter of 1886-87, he received news of the devastation via this sketch by cowboy artist Charles M. Russell, titled “Waiting for a Chinook—The Last of 5,000.”

– True West Archives –

In the Wild West, cattle were a staple—cattle drives, cattle towns, cattle herds, cattle ranches. Cattle were king through the 1870s up until the mid-1880s.

By 1885, beef prices were falling and much of the open range was overgrazed, mainly because cattle barons had built up herds too large for the land. But the barons—many of them Europeans—who owned huge swaths of land from Canada to Mexico, maintained business as usual. Until they couldn’t.

The summer of 1886 was unusually hot and dry as a drought hit. More grass died. Brush fires burned off even more. Water sources dried up. Other signs pointed to a tough winter ahead—geese going south earlier, cattle growing thicker fur, beaver stacking more wood for dens.

In November, the snow came. No place was safe—California got nearly four inches in San Francisco. North Texas and the Panhandle were inundated. “Day after day the snow came down, thawing and then freezing and piling itself higher and higher. By January the drifts had filled the ravines and coulées almost level,” remembered Theodore Roosevelt, who was ranching in Dakota Territory at the time.

Blizzards roared across the West in January. Temp-eratures dropped to 30 below in some places. They hit 43 below the next month.

Warm Chinook winds began the thaw by March 1887. An estimated hundreds of thousands of cattle carcasses littered the land—many pushed up against wire fences or lining roads. Total losses went unreported, but in some areas, up to 90 percent of the herds were wiped out. Small ranches—what few existed—went out of business. Even some huge cattle companies declared bankruptcy.

Roosevelt wrote a friend, “Well, we have had a perfect smashup all through the cattle country of the northwest. The losses are crippling. For the first time I have been utterly unable to enjoy a visit to my ranch. I shall be glad to get home.”

He was lucky to have a home to go to. Most Westerners did not; they had lost theirs in the Great Die-Up.

Thousands of cowboys were out of jobs. Some drifted back East or looked for work in Western towns. Others (like members of the Wild Bunch) turned to less honorable pursuits that included rustling and outlawry.

Those who tried to carve out a ranch by claiming unbranded calves ran smack into the old guard cattle barons. Range conflicts broke out, perhaps most notably the Johnson County War in Wyoming.

That deadly winter had changed cattle country. As the Rocky Mountain Husbandman newspaper in Diamond City, Montana, reported, “…range husbandry is over, is ruined, destroyed, and it may have been by the insatiable greed of its followers.”

Barbed wires split the ranges. Smaller cattle operations became the norm. Foreigners felt leery about investing out West. Cowboys became more of an iconic symbol than a constant presence. Cattle were no longer king.

Historians still debate over when the Old West died. The Great Die-Up may not have been the end, but the disaster certainly played a role in finishing the era.