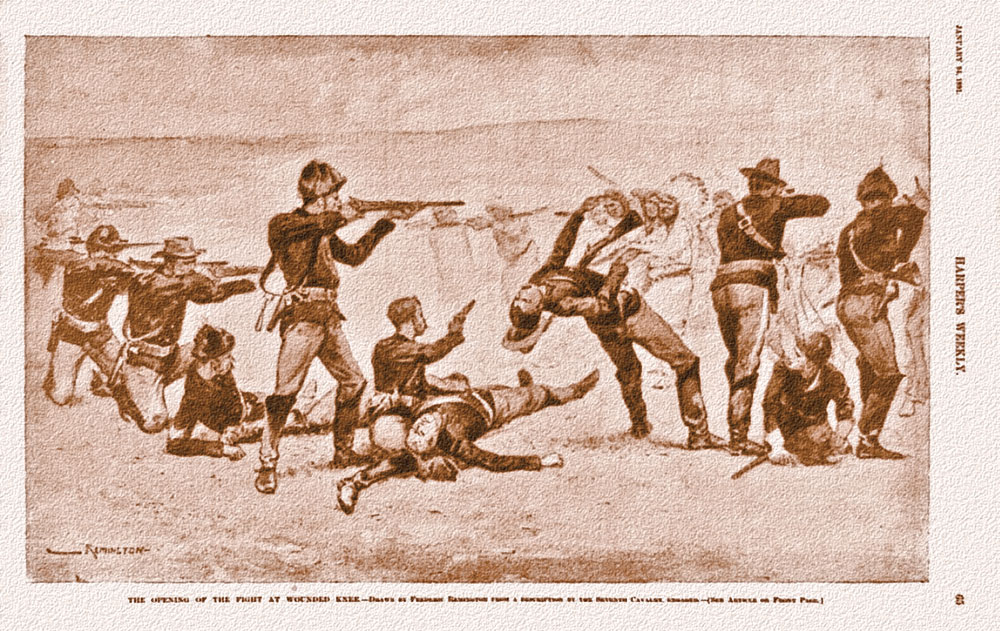

The horrified woman ran with all her heart through chaotic, thunderous reports of carbines, rifles and pistols that were dwarfed only by the din created by Hotchkiss guns. Determined to outrun the icy fingers of cruel fate and take her infant daughter to safety, the woman gulped in frigid air and ran an eighth of a mile before she heard the close approach of a man on a horse. He was one of the soldiers!

The desperate mother held her infant high and begged for her child’s life. Showing no mercy, the soldier fired two shots into the woman’s chest. She crumpled to the ground, holding on to her infant as her lifeblood soaked into the snow.

Death was a whirlwind, scything through Big Foot’s camp at Wounded Knee Creek on December 29, 1890. Considered by many to be the last battle of the Indian Wars, the fight began as the U.S. Army attempted to disarm the Ghost Dancers; the police assassination of Sitting Bull had fanned distrust among the Lakotas. At Wounded Knee, an accidental gunshot set off a torrent of confused firing. Soldiers killed, with little consideration given to age or gender.

On the first day of the new year, burial parties began the grim work of burying the hundreds of bodies. A blizzard had covered the roughly 200-acre site with a fresh blanket of snow. Among five dead Lakota women huddled against a cut bank, George E. Bartlett found one frozen corpse holding a still living infant. The mother used her body to shield her baby from freezing. Bartlett had difficulty removing the frostbitten baby from the dead mother’s icy embrace.

Taken to Pine Ridge Agency to recover, the baby came to the attention of Gen. Leonard Wright Colby, a hero of the Civil War siege of Mobile and a future U.S. assistant attorney general. Colby’s Nebraska troops had not been engaged at Wounded Knee, yet the general recognized an opportunity to emulate his hero, Andrew Jackson, who, in 1813, adopted Lyncoya, a boy found on a battlefield near his mother’s corpse. Colby and his aide-de-camp, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, bartered with the foster family for the “Indian relic,” agreeing to a price on January 6.

A woman disapproving of this deal, however, removed the child to a nearby Indian encampment, supposedly Red Cloud’s. Until the terms of surrender concluded, troops had been forbidden by Gen. Nelson Miles from going to such encampments.

Colby was a risk taker. He once convinced a lynch mob to let him live and reportedly swallowed poison used in a murder to prove a client’s innocence. But he dared not cross Miles. He sent Lt. Edward E. Casey to reclaim the baby. But when Casey died from a shot to the head by a well-aimed Winchester during the attempt, Colby took on the mission.

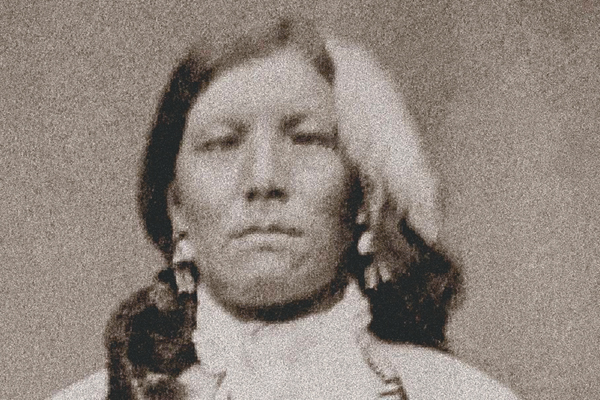

On January 14, in the guise of a half-blood Indian, he joined Ghost Dancers heading to a meeting with Gen. Miles. The honey-tongued Colby, speaking through an interpreter, spun a tale of needing the child because his wife was barren. He nearly overplayed his hand. When he reached out for the infant, a woman exclaimed, “Zintkala Nuni,” which translates to “Lost Bird.” But Colby got the baby, and the baby now had a name: Zintkala Nuni.

Colby’s wife, Clara, an influential suffragette, raised Nuni. Nuni led a difficult life. Colby took advantage of his adopted daughter to raise significant sums of money, yet he barely spent time with her. Clara’s political activities left Nuni bouncing between family members, nannies, boarding schools and institutions. In time, the general abandoned the two for a young mistress, leaving them in desperate financial condition.

Nuni tried to return to her people, only to discover she did not fit comfortably in either the culture of her origin or her adopted one. To the Lakotas, the piano-playing, scandalously-clad, English-speaking woman was white. To the whites, her appearance and personality set her apart as an Indian.

She visited Wounded Knee whenever her travels brought her nearby and attempted to find her blood relatives. The beautiful woman was married several times to non-Indians, with her first husband giving her a wedding present of syphilis. This disease eventually cost her the sight of one eye. Children were born, died and even given up to others.

As a piano player, she worked in Wild West shows, including Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, run by her father’s former aide-de-camp. In 1920, after brief careers in vaudeville and in silent movies, she volunteered to nurse the sick during an influenza epidemic. With her constitution already weakened by syphilis, she contracted the flu and died on Valentine’s Day.

Originally buried in California, her remains rejoined those of her Lakota mother, who died trying to save her a century before. With her internment at Wounded Knee in South Dakota in 1991, Nuni was home at last.

Terry A. Del Bene is a former Bureau of Land Management archaeologist and the author of Donner Party Cookbook and the novel ’Dem Bon’z.