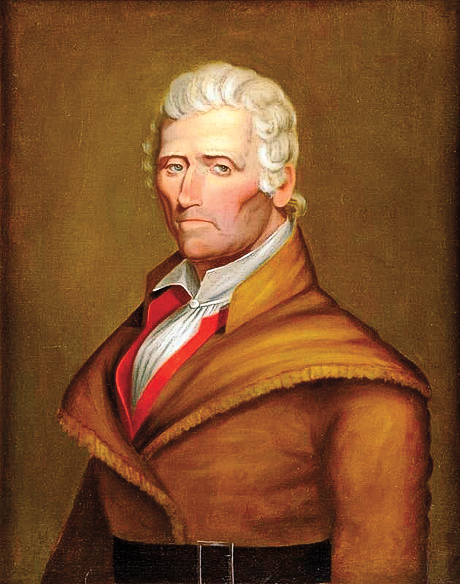

Neither Meriwether Lewis nor William Clark ever mentioned meeting Daniel Boone on May 24, 1804, when they stopped at the village nicknamed Boone’s Settlement, on the north bank of the Missouri River, some 60 miles from St. Louis, Missouri. The captains of the transcontinental expedition talked with the settlers, procured corn and butter, and then resumed their voyage. Had they met Daniel, they almost certainly would have recorded the moment—symbolizing the passing of the torch from the old American frontier to the new.

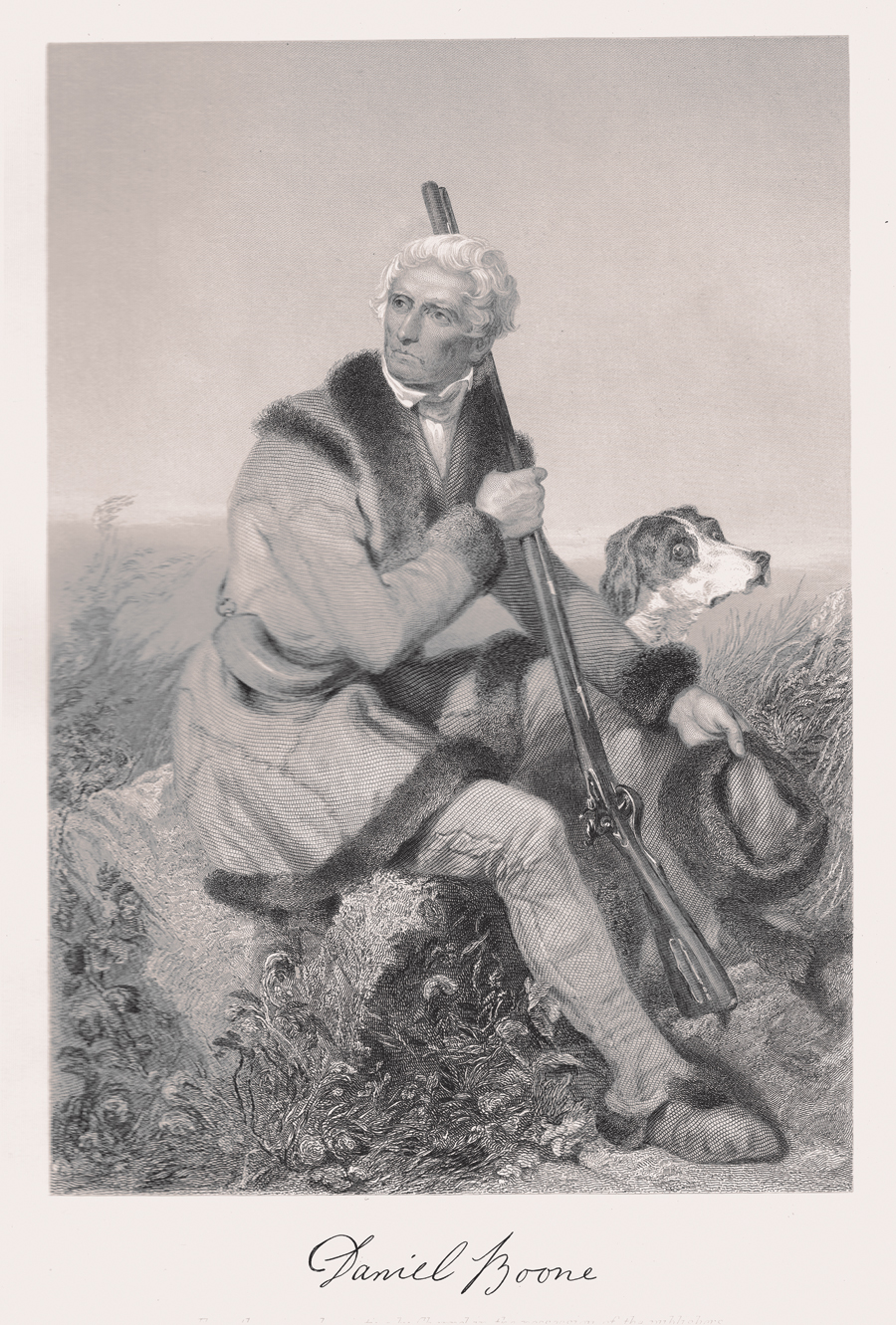

Although chief administrative officer of the district, the absent 69-year-old Daniel might well have been pursuing his favorite pastime: hunting and trapping. Daniel lived a life full of daring adventure, exploring dangerous country that would eventually take him high up the Missouri River.

The Ozark Mountains had become Daniel’s new Kentucky wilderness, and he, his sons and friends roamed deep into the forested valleys. Now and then, the resident Osages would angrily confiscate the party’s beaver pelts and deerskins, much like the Shawnees of old Kaintuck did during the 1760s and 1770s. By way of the Cumberland Gap, Daniel helped blaze a path into Kentucky to found Boonesborough, one of the first settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains. In 1799, he and his family moved to Missouri, which was part of Spanish Louisiana. By 1808, Daniel and his fellow trappers had to outride pursuing Indians, probably Osages, whom they managed to deter from the chase only by cutting loose their traps and pelts.

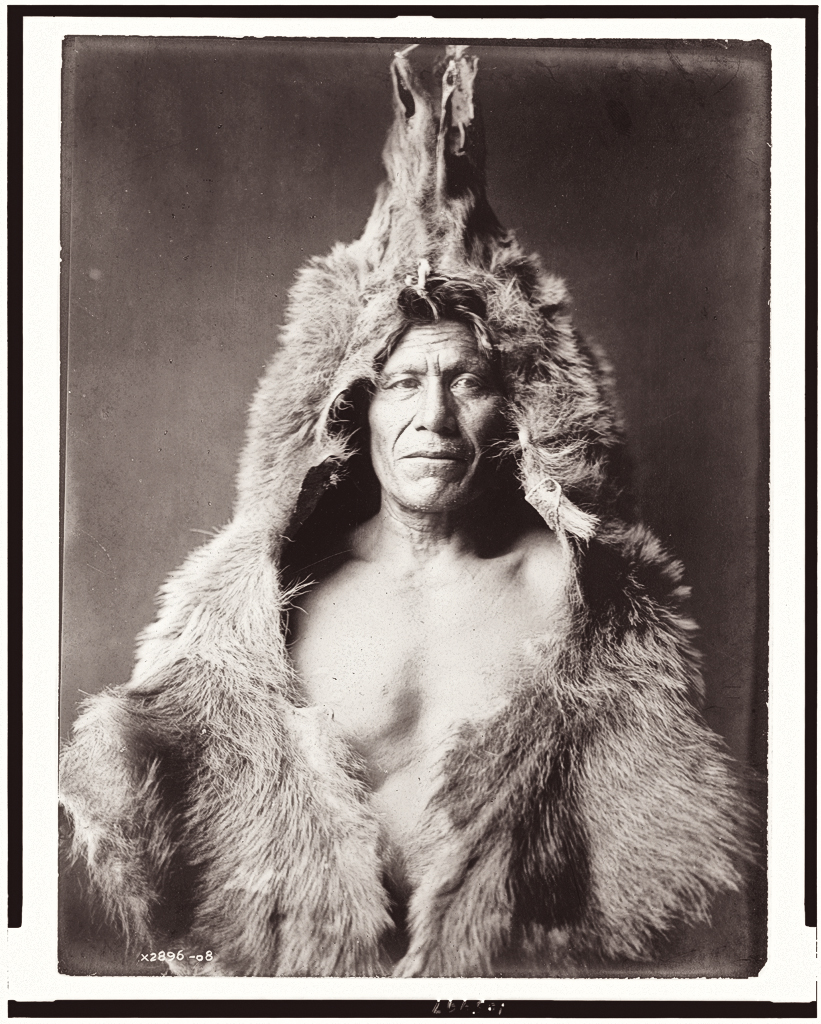

Two years later, after a health crisis aggravated by increasing rheumatism, Daniel welcomed into his home two old friends from Kentucky, Michael Stoner and James Bridges, then in their mid-50s. They were bound for the Upper Missouri River country, a fur-rich region traversed by only a few daring adventurers, including John Colter, George Drouillard, Manuel Lisa and Andrew Henry. The unpredictable Arikara, Sioux and Blackfoot tribes made journeys extra hazardous. But Daniel, even at 75, was not a man deterred by the perils of Indian country.

In the early fall of 1810, the three greying backwoodsmen—Daniel, Stoner and Bridges—along with Flanders Callaway, Will Hays Jr. and Derry Coburn, a slave of one of Daniel’s sons, traveled “high up the Missouri trapping,” in the words of Stoner’s son. Hays recorded that they got as far as the Yellowstone River.

Six months after their departure, at least one of the boats returned “with housing over the cargo,” St. Charles resident Stephen Hempstead recalled, adding that Coburn was rowing, while Daniel was handling the rudder. Daniel had probably turned back about midway, perhaps somewhere in Nebraska or even South Dakota—the true beginning of the Great Plains—while the healthier, younger Stoner and Bridges continued on toward Yellowstone.

Scottish naturalist John Bradbury, about to travel up the Missouri with the Astorian Expedition, entered in his journal that Daniel “had lately returned from his spring hunt, with nearly sixty beaver skins.” This marked one of Daniel’s most bountiful hauls, at a time when beaver hats were still de rigueur.

During the War of 1812, numerous reports and rumors swirled about Sauk raids in the vicinity of Daniel’s home. Although his advanced age prevented him from joining the local mounted rangers, his presence in the settlement, rifle in hand, was reassuring.

Toward the end of 1815, Daniel, 81, left home in the company of friends, including a Shawnee neighbor called “Indian Phillips,” who had a reputation as one of the best hunters in Missouri. Again, Daniel traveled by water, possibly in a pirogue or in a mackinaw boat.

In April 1816, he reached Fort Osage, on the Missouri River 250 miles to the west, not far from today’s Independence, Missouri. “We have been honored by a visit from col. BOONE, the first settler of Kentucky,” wrote an officer in the fort. “…The colonel cannot live without being in the woods. He goes a hunting twice a year to the remotest wilderness he can reach…He left this [place] for the river Platt[e], some distance above.”

The officer also recorded Boone’s travel plans for the fall: “I intend…to take two or three whites and a party of Osage Indians, and visit the salt mountains, lakes and ponds, and see the natural curiosities of the country along the [Rocky] mountains. The salt-mountain is but 5 or 600 miles west of this place.”

Daniel traveled only as far as today’s Atchison, Kansas, on the prairie fringes of the Great Plains, his son Nathan remembered, before ill health forced Daniel to turn back. The aged frontiersman’s remaining hunts were few and short-lived: he died in 1820, at the age of 85.

History cannot deny that, had Daniel Boone been a few decades younger, his reputation as a Mountain Man might resonate today alongside Old West icons Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith, Joseph Walker and Kit Carson.

Gary Zaboly, fascinated with America’s folk heroes, has illustrated Texas history books, including Blood of Noble Men: The Alamo Siege and Battle and Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution, and written An Altar for Their Sons: The Alamo and the Texas Revolution in Contemporary Newspaper Accounts.