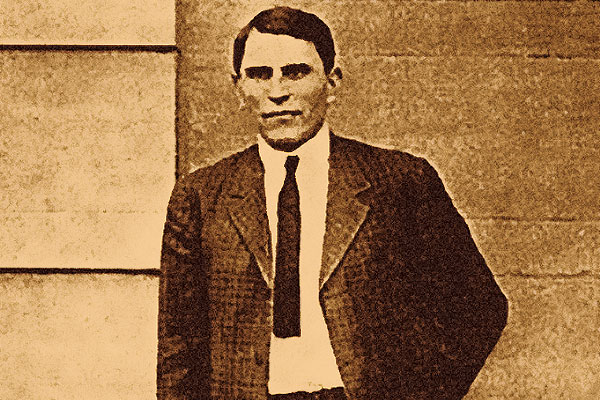

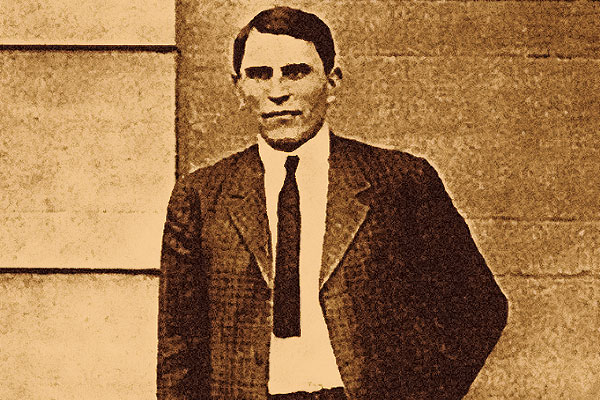

One hundred years ago this month, Henry Starr set out to make history. The career outlaw wanted to rob two banks at once, succeeding where the Dalton Gang had failed in 1892.

His luck seemed good; in the previous six months, he had pulled at least 14 bank jobs, netting more than $26,000. But he should have learned from the Daltons.

In mid-March, Starr and six pals camped outside Stroud, Oklahoma, about 60 miles northeast of Oklahoma City. When the men cased the town, law officers thought they were just some hunters.

The gang was on the hunt—for cash. On mid-morning of Saturday, March 27, the not-so magnificent seven rode into Stroud. One stayed with the horses, tied up at the local stockyards, while the rest walked toward the banks. Nobody took notice. The well-dressed men didn’t wear masks or flash guns.

Lewis Estes and two cohorts entered the First National Bank, while Starr led two outlaws to the Stroud National Bank about a block farther on. The Estes outfit smoothly collected more than $4,000, but Starr fell for a ruse—one that had also frustrated the Daltons during their dual bank robbery in Coffeyville, Kansas.

The bankers convinced Starr that the vault was on a time lock and wouldn’t open until the close of business. They were lying, but Starr didn’t want to waste time. He and his crew scooped up about $1,750 from the cash drawer, took three people hostage and headed toward the horses.

They met up with Estes and company—and their seven hostages—outside the First National Bank. The six outlaws used the 10 civilians as shields.

Word of the robberies had spread throughout Stroud, and a number of men began firing over the heads of the 16. The hostages scattered, and the outlaws made a run for the horses, dodging bullets and snapping off shots as they went.

From a grocery, the owner’s son, 20-year-old Paul Curry, grabbed a sawed-off rifle used to kill hogs and opened up. One shot hit Starr in the upper left thigh, shattering the bone and leaving him unable to move. Curry then turned the rifle on Estes; the bullet passed through the outlaw’s neck and into his lung. Estes got to his horse and rode out of town, but he collapsed a couple of miles later. A posse brought him back to Stroud. Three other gang members were also arrested.

Both Estes and Starr pleaded guilty to the robberies. Estes got five years. The judge sentenced Starr to 25 years, based on his criminal career stretching back at least 24 years. But some kind-hearted bureaucrats believed Starr was reformed after just four years in prison and set him free.

Starr tried to capitalize on his Stroud escapade. In 1919, he put together a film based on the incident, called A Debtor to the Law, a crime-does-not-pay morality tale. Strangely, his partners in the venture were just as crooked as the bandit, stealing an estimated $15,000 from Starr.

He only knew one way to recoup the cash. Yet when he tried to stick up a bank in Harrison, Arkansas, in February 1921, he was mortally wounded.

Starr died at the age of 47, not having learned much from the Dalton debacle…or even from his own movie.