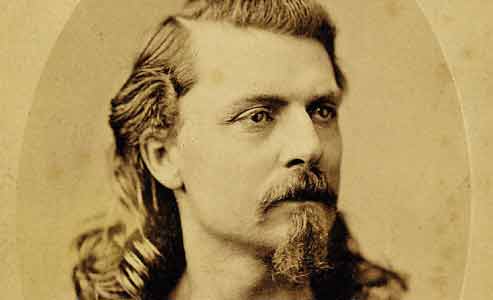

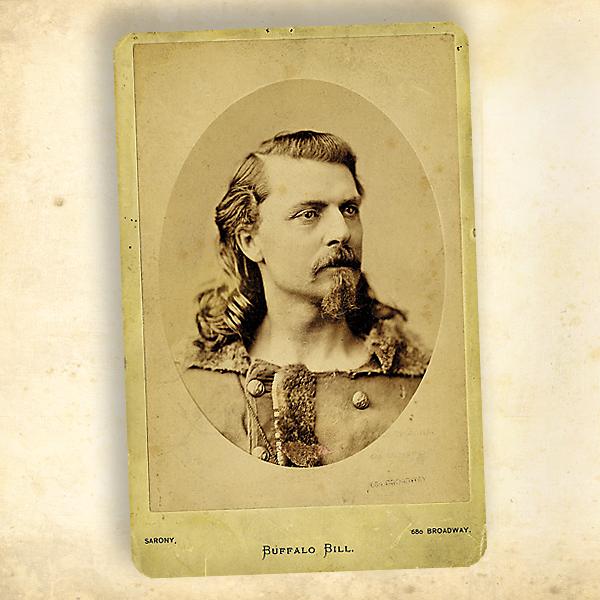

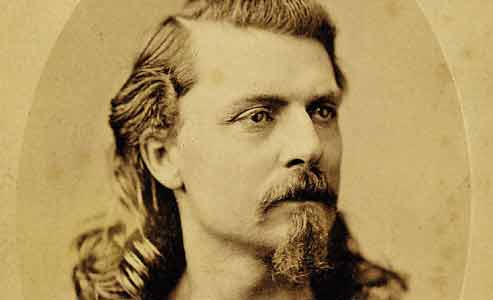

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody may have appeared on the world stage as a confident showman, star of the Wild West show he formed in 1883. But he first learned how to dramatize events as an actor…often an inept one. Even worse: a dangerous one.

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody may have appeared on the world stage as a confident showman, star of the Wild West show he formed in 1883. But he first learned how to dramatize events as an actor…often an inept one. Even worse: a dangerous one.

Shortly after he began his acting career in 1872, he and costar John Baker “Texas Jack” Omohundro thrilled audiences with acts that promised to “Wipe the redskins out.” In their exuberance during one simulated Indian fight, actor W.J. Halpin, in the role of Big Wolf in “The Scouts of the Prairie,” was inadvertently stabbed in the abdomen. He died of his injury less than a week later.

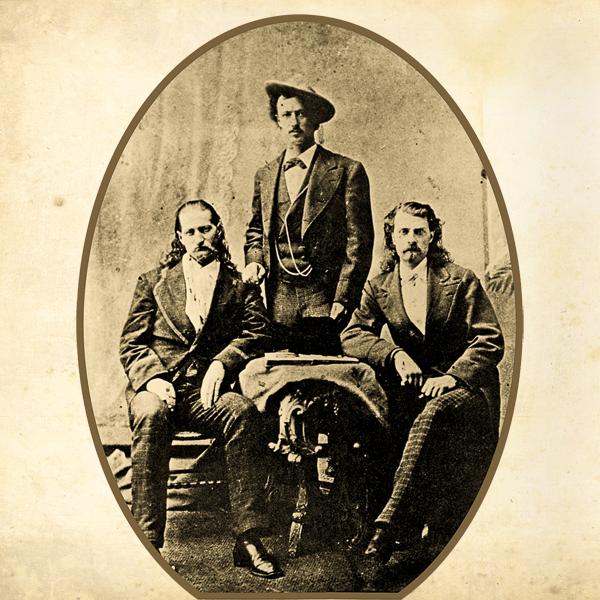

Another of Cody’s costars could have done similar serious damage. Beginning in September 1873, James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok toured with the troupe for six months. His increasing boredom with playacting led him to purposefully torment the extras playing Indians. Instead of shooting over their heads during mock battles, he aimed at their legs, causing them to jump about instead of lying down and playing dead. Cody had to remonstrate with him more than once.

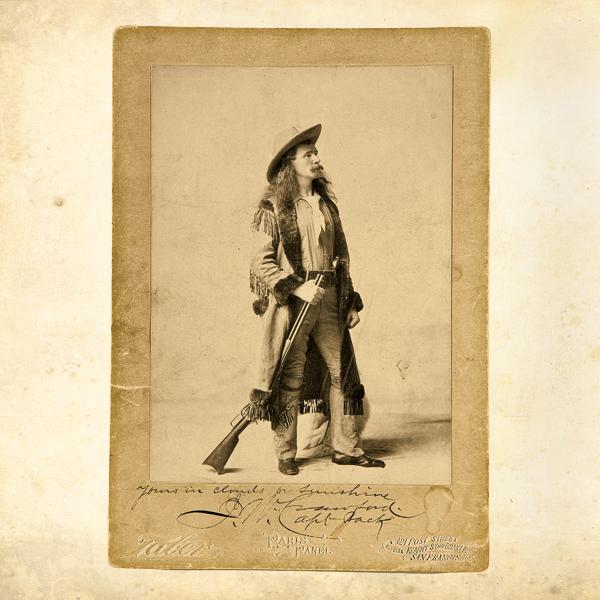

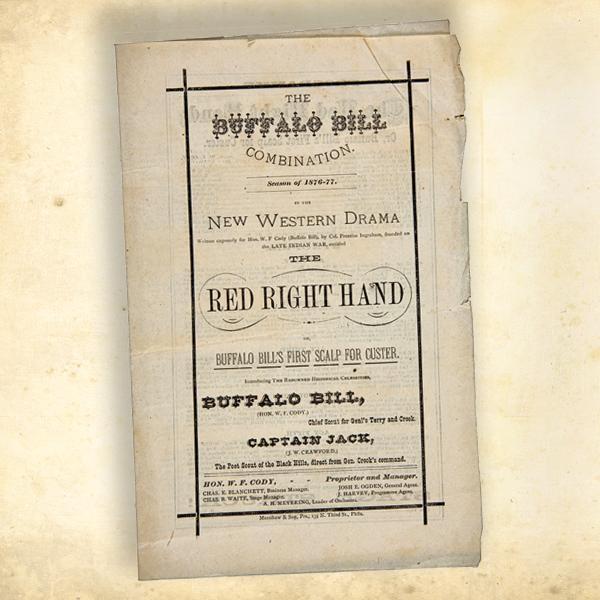

When Cody worked with fellow scout John Wallace “Captain Jack” Crawford during his 1876-77 season, Crawford prepared the blank cartridges Cody used onstage. Once, Crawford delegated the job to a property man, instructing him to stop the end of each shell with paraffin. The man thought a tallow candle would do, so he poked candle grease into the cartridges, six for each pistol. The first shot melted the wax, and sparks set off all the other cartridges. No one was injured, though an excited child ran out to alert the town that Cody was “massacreing [sic] the whole audience.”

Cody fared luckier than his partner. In June 1877, during a performance of “The Red Right Hand” in Virginia City, Nevada, Crawford was engaging Cody in a fight on horseback when he drew his cocked pistol and accidentally shot himself in the groin. He dismounted, “rather unceremoniously,” and blood began to soak his pants. For a moment, he carried on, in the spirit of the “show must go on,” but when he reeled and began to fall, fellow actors carried him off stage. Crawford needed crutches for several weeks.

While misfortunes involving actors were regrettable, danger to the audience was unthinkable. In Baltimore, Maryland, on September 10, 1878, while charging his horse up a fake mountain onstage, Cody turned to fire at his Indian pursuers. The shot went wild and struck a young boy named Michael Gardner. Despite his having checked the ammunition before show time and deciding the bullets would hardly penetrate a cigar box, Cody had fired the errant, underloaded bullet (about five grains of powder per bullet) from a considerable height. Because the boy had been leaning over the front of the gallery, the bullet’s trajectory proved disastrous. His lung punctured, Gardner was not expected to last the night. He eventually did recover, however, and Cody transported him to his Nebraska ranch for further recuperation. Newspapers condemned the recklessness and hoped such tragedy would lead to reform.

Occasionally the thrill of near death engendered outsiders to try their skill, sometimes with violent results. After a performance in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in October 1881, Cody left the theatre with his wife and daughters. Suddenly, a man on horseback rode to within a few feet of the family and fired. Cody’s publicity agent witnessed the shooting and pointed the gunman out to police. Speculation had it that he was a “crazy crank” too enthused by Cody’s fancy shots during the play.

Cody was fortunate. Other frontier performers in the 1880s, attempting to best or at least equal Cody’s marksmanship displays, titillated audiences by shooting their rifles at an apple placed on the head of an assistant, often a pretty girl. These William Tell acts occasionally met disastrous, even deadly, results. In an 1882 article titled “One Good Result,” a journalist described the contortions shooters had exercised to perform their treacherous feats. From shooting while standing on their heads to firing while leaning across the back of a chair with head thrown back, marksmen executed increasingly perverse gymnastics to incite audiences’ fear and wonder.

The well-publicized killings of at least three people during such grisly performances broadened the call for reforms. The public was hard pressed to decide whether to blame the shooter or the law that permitted the dangerous exhibitions of skill.

So, with a heightened realization of potential jeopardy, performers gradually began to eliminate human targets in favor of glass balls. These included Annie Oakley, a popular performer who joined Cody’s Wild West show in 1885. Even “Little Sure Shot”—whom one could bet would never miss, even when she used a hand mirror to shoot backwards—shot at glass balls, never trusting to luck or skill.

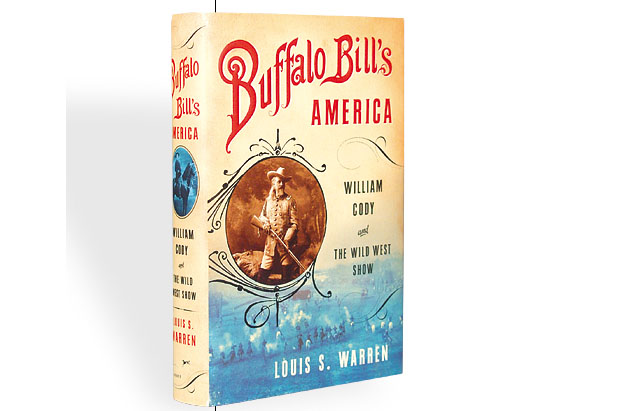

Sandra K. Sagala is the author of Buffalo Bill on Stage, published by University of New Mexico Press, and Buffalo Bill on the Silver Screen, published by University of Oklahoma Press.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions, May 22, 2010 –

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 10, 2012 –

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 13, 2008 –