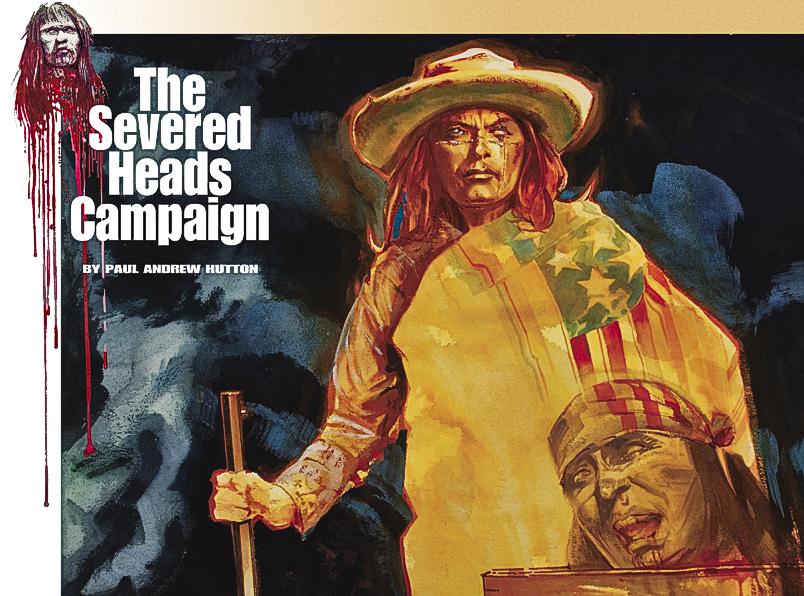

Mickey Free rode into Camp Apache on April 27, 1874, with the bloody severed head of the renegade warrior Pedro hanging from his saddle.

Mickey Free rode into Camp Apache on April 27, 1874, with the bloody severed head of the renegade warrior Pedro hanging from his saddle.

The delivery of the head by the enigmatic scout to Capt. George Randall marked the beginning of the end of one of the most remarkable, and brutal, military campaigns in American history.

Eating His Words

Almost exactly one year before, on April 9, 1873, Arizona commander George Crook had declared an end to his first Apache campaign, which press and politicians alike had proclaimed as both brilliant and decisive. Crook congratulated his troops, who he said had “outwitted and beaten the wiliest of foes…and finally closed an Indian war that has been waged since the days of Cortez.”

President U.S. Grant responded by promoting Crook up two grades to the rank of brigadier general as the Arizona press hailed this “Napoleon of successful Indian fighters.”

Crook soon had his hands full with those he casually declared “my Indians.” The new reservation created by presidential envoy Vincent Colyer at San Carlos was an extension of the White Mountain reservation headquartered at Camp Apache, and it had quickly turned into an administrative nightmare.

Interim agent Dr. R.A. Wilbur, the former agent for the Tohono O’odham, had practiced chicanery for so long that fraud was his normal business conduct. His constant cheating of the Indians and the government in ration issues was bad enough, but he also meddled in volatile Apache politics at San Carlos in hopes of securing the agent position.

Permanent agent Charles Larrabee arrived in March 1873. The former Union officer learned that rumors spread by Wilbur about him had incited Chunz, Chan-deisi and Cochinay to plan to kill Larrabee. He had Aravaipa leaders Eskiminzin and Capitán Chiquito’s support, but Larrabee was determined to win over the recalcitrants by giving in to their demands for increased rations.

Major William Brown and a detachment of the 5th Cavalry arrived to back up the new agent, but Larrabee dismissed them. The Apaches feared troops who camped near them.

Scout Archie McIntosh, sensing serious trouble, urged Brown to stay, but the major did not wish to undercut civilian control at the agency. He did, however, leave Lt. Jacob Almy with 5th Cavalry troops to provide some security. This scared Eskiminzin and Capitán Chiquito into moving their people from the agency to the nearby mountains. They knew that trouble was brewing.

Bloodshed at San Carlos

On May 27, ration day at the agency, more than 1,000 Apaches gathered around Larrabee’s crude storehouse. Nearly half of the men were armed. After Chan-deisi loudly threatened the new agent, interpreter Merejildo Grijalva and a handful of troopers went in search of him. Almy rushed to the scene to join in the search. A shot rang out amongst the milling crowd, and Almy staggered toward Grijalva.

“Oh, my God!” Almy cried, as he clutched his bloody side. Another shot rang out, and the lieutenant’s skull exploded.

The soldiers opened fire, but the Apaches had already scattered. A shaken Larrabee promptly resigned his position and turned San Carlos over to the Army.

The laurels won by Crook in his celebrated triumph over the Apaches were rapidly wilting. Crook ordered Brown to take over as a temporary agent, but not to accept Indian surrender until the heads of Chunz, Cochinay and Chan-deisi were delivered. Crook meant what he said—he wanted their actual heads for public display at San Carlos.

Standoff at San Carlos

At Camp Verde, affairs were also about to spin out of control.

Delshay had remained troublesome ever since the Army forced him to settle on the reservation. He kept his Tonto Apache and Yavapai friends and relatives in a constant state of agitation.

Camp Verde had a remarkable leader in Walter Schuyler. Within weeks, the lieutenant and scout Al Sieber had overseen the planting of nearly 60 acres of land with melons and vegetables favored by the Indians, as well as many more acres prepared for corn and barley. They also constructed a water wheel and dug an irrigation ditch.

Even as this good work progressed, rumors swirled that the “Indian Ring,” headquartered in Tucson, had lobbied Congress to have all the Camp Verde Indians moved to San Carlos. The motive being that Tucson merchants were issued nearly all the federal contracts for San Carlos. The news flamed the smoldering discontent of Delshay and his followers.

Another issue that upset the Indians was Crooks’s order that all must carry a number, on tags distinctly shaped to designate the various bands. Any Indian found off the reservation had to produce his tag and a written pass that corresponded to the tag number. Many warriors, contemptuous of this dehumanizing system, exchanged their tags as currency in games of chance.

With ominous news from San Carlos, Schuyler realized he faced similar problems. He and Sieber were fighting a two-front war—one with the Apaches and the other with the federal Indian Bureau.

Schuyler fretted over Delshay and wrote Crook, requesting permission to arrest him. Crook approved, but warned the young lieutenant not to “make the arrest unless you are sure of success, as a failure will lead to bad consequences.”

Crook’s anxiety was well placed, for Delshay was plotting to kill Schuyler, an act that would gain him notoriety, just like Chunz, Chan-deisi and Cochinay had won by killing Almy at San Carlos.

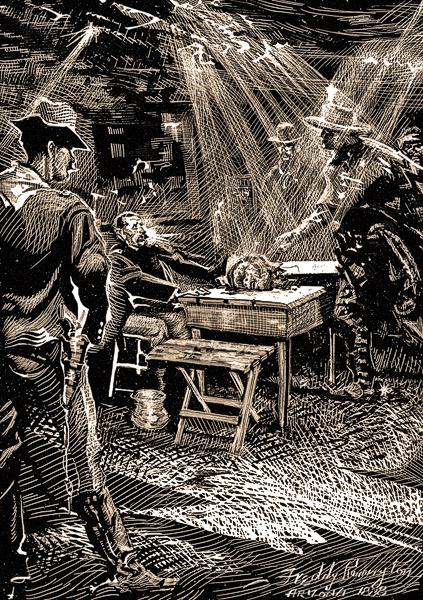

To arrest Delshay, Schuyler ordered his rancheria to Camp Verde for a census count. But Delshay’s spy, Tonto interpreter Antone, secretly unloaded Schuyler’s rifle just before the parley.

When the brash lieutenant informed Delshay that he was under arrest, the chief laughed. Through Antone, the chief said that he was no man’s prisoner.

“You damned thief, you’d better make your little prayer, and be quick about it, too!” exclaimed Schuyler, as he leveled his rifle at Delshay and pulled the trigger. Click went the Winchester, then click again and again.

Delshay’s warriors suddenly jumped to their feet, throwing aside their blankets to reveal weapons. Sieber, though, had wisely gathered his scouts as a rear guard, and they rushed forward to surround the lieutenant and his men. It was a standoff.

Delshay and his followers, along with Antone, bolted, while Sieber restored order and hustled Schuyler to his quarters. The lieutenant was fortunate to be alive, although he now faced the grim task of informing Crook that more than 1,000 Apaches and Yavapais had fled the reservation.

By September 18, Schuyler and Sieber, with 15 troopers and 23 Indian scouts, were in the saddle in pursuit of Delshay and his band. Most of the people who had fled Camp Verde returned, but small Apache raiding parties struck all around Prescott.

Schuyler and Sieber remained in the field for three months. They scouted east to the Aravaipa Canyon above old Camp Grant, fought a series of sharp skirmishes, in which their little command killed 83 Apaches, and led 26 prisoners back to Camp Verde. Delshay was not among the prisoners, for he had once again eluded the Army.

The Severed Heads List

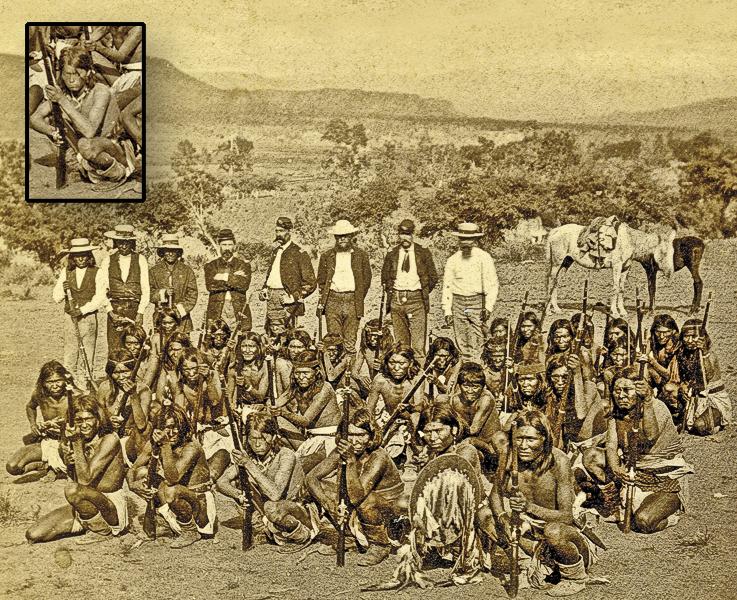

To force the Apaches onto their assigned agencies, Crook set several columns in motion, from Camps Verde, Whipple and Lowell. The largest, from Camp Grant under Randall’s command, with McIntosh as chief scout, marched north to Camp Apache to unite with 5th Cavalry troopers and White Mountain Apache scouts.

“I have requested Maj. Randall to try & have Delche’s [sic] head,” Crook wrote Lt. Schuyler, “but if he has a strong party with him it is doubtful whether Maj. Randall’s scouts will succeed.”

The general sent out a list of prescribed Apaches who were to be killed and the bounties that would be paid upon the delivery of their heads. Crook surmised that the Apaches would turn on Delshay, Chan-deisi, Chunz, Cochinay and others in exchange for the reward or simply as a way to end the hostilities. “The more prompt these heads are brought in,” he told Schuyler, “the less liable other Indians, in the future, will be to jeopardize their heads.”

Randall had reported unrest among his camp’s Apaches at about the same time as Almy’s murder at San Carlos. The unrest had even spread among the scouts. After a tiswin-fueled brawl on July 16, one scout was dead and two others had deserted.

This was compounded by a whooping cough epidemic in September that killed three more scouts, as well as many other Apaches, and led many of the Western Apache bands to avoid congregating on the reservation. The same outbreak, which also struck Camp Verde, had contributed to the unrest leading to Delshay’s outbreak.

Crook ordered a consolidation of the scouts in hopes of creating an elite force on the reservation. “These Indians will be selected from among the best of their several tribes,” Crook instructed his officers, and “will constitute the police force of the reservation….”

Rolling in Heads

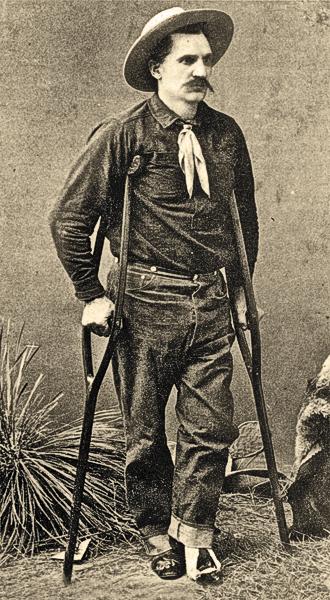

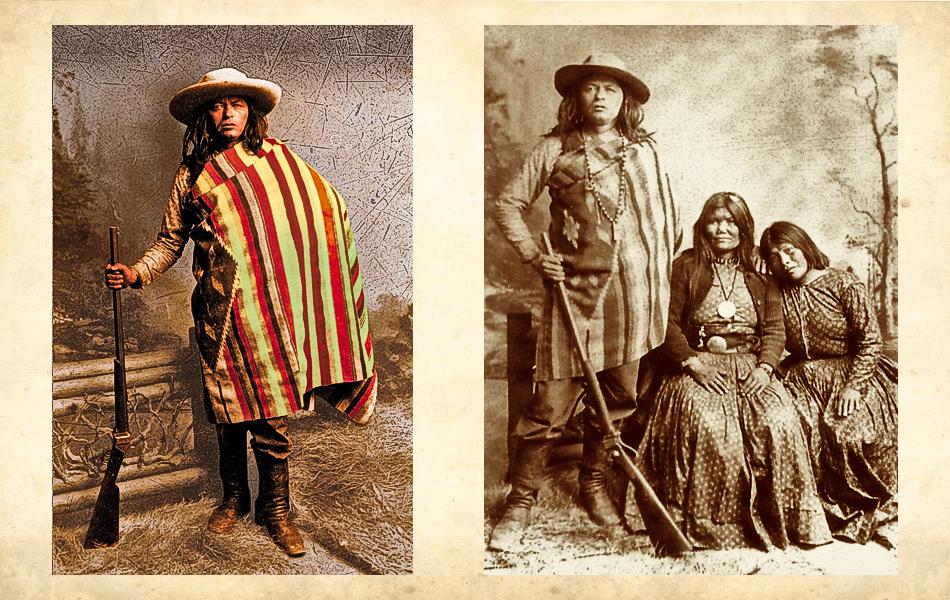

Sergeant Mickey Free was among those in service at Camp Apache. This remarkable 26 year old lived precariously between the conflicted worlds of the Apaches and the white invaders, never accepted by either, but invaluable to both. His 1861 kidnapping had started the war, and both sides curiously placed the blame for the conflict on him. Apaches called him Coyote, after their trickster animal, never quite certain if he was friend or foe.

Free, with 39 fellow scouts, accompanied 1st Lt. John Babcock with B Troop 5th Cavalry on an expedition in December 1873. In the brutal weather, the scouts located two rancherias in the mountains west of Camp Apache, captured 10 women and children, and killed 21 warriors. They returned to Camp Apache with their prisoners on January 4, 1874.

In early February, Capt. Randall, with Free and 60 Apache scouts, and several 5th Cavalry companies, marched west along the Salt River and turned south to strike Eskiminzin’s village in the mountains northwest of San Carlos. The battle left all the property and animals, along with 34 women and children, in Randall’s possession. Eskiminzin surrendered.

Two months later, Randall ordered Free, with 14 White Mountain scouts, to bring in Pedro, a notorious warrior who had fled the reservation with several companions. Free left Camp Apache on April 26. He returned the next day to deliver Pedro’s head to Randall.

The military authorities were soon rolling in heads. Within three miles of Tucson, Cochinay was bagged by Apache scouts who delivered his head to San Carlos in May. A delighted Crook wrote Schuyler on June 23: “Recent telegram from Babcock says that John Daisy’s [Chan-deisi’s] head was brought into Camp Apache the other day, which leaves now only Chunz’s head on his shoulders…. Start your killers as soon as possible after the head of DelChe [sic] & Co.”

Apache scouts ran Chunz to the ground in the Santa Catalina Mountains above Tucson in July. On July 31, Babcock wired Crook from San Carlos to report that the heads of Chunz and six of his compatriots were neatly arrayed on the post parade ground.

Delshay’s days were numbered. Schuyler’s Tonto scouts claimed first kill. They went old school and brought in a scalp with one ear attached and handed it to surgeon William Corbusier. He dispatched the grisly trophy by courier 14 miles downriver to Camp Verde. Sieber’s scouts identified the scalp by a pearl shirt button dangling from the ear lobe. Another warrior upped the ante when he delivered Delshay’s entire severed head.

Crook was not disturbed by these contrasting claims. “When I visited the Verde reservation, they would convince me that they had brought in his head,” Crook declared with considerable amusement, “and when I went to San Carlos, they would convince me that they had brought in his head. Being satisfied that both parties were earnest in their beliefs, and the bringing in of an extra head was not amiss, I paid both parties.”

On September 30, Crook reached Camp Apache after a hurried visit to San Carlos to meet with Babcock. He congratulated Capt. Randall, Corydon Cooley and the White Mountain scouts for their excellent work in breaking up the last of Delshay’s band.

On August 18, Cooley, accompanied by Free and the Company A scouts, had surprised the remnants of Chappo’s demoralized band at Black Mesa and killed 13 warriors. On their way back to Camp Apache, the scouts had surprised another small rancheria at the northern end of the Sierra Anchas and killed 10 more Tontos.

These constant scout movements had made it impossible for any of the Apache bands to remain off the reservation. Harassed, demoralized and starving, they returned to the agencies in ever greater numbers. Crook’s brutal tactics had proven eminently successful—despite their rather Medieval methods—and brought about a brief peace in Arizona Territory.

THE NEW FACE OF APACHERIA

On December 4, 1874, Camp Verde hired Mickey Free as an Indian interpreter for $125 a month—a substantial increase over his $17-a-month scout wage. His scouting duty for Gen. George Crook had paid rich dividends, despite the fiction employed to enlist him as a White Mountain Apache scout. Everyone now knew his story—that he had been kidnapped by the Aravaipa Apaches in 1861, in the so-called Bascom Affair, and that he was Mexican, not Apache. Free, unlike the other Apache scouts, could come and go as he pleased, like any other Arizona citizen.

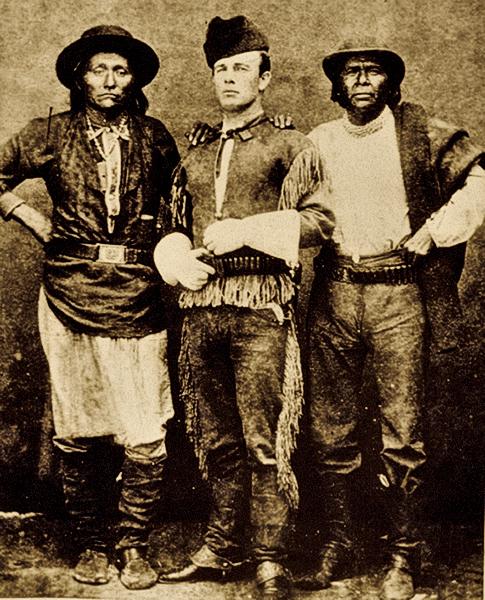

The day after he was hired as interpreter, Free greeted Lt. George Eaton, his new boss, upon his return from a scout into the mountains. With Eaton were 20 Indian scouts under the command of Al Sieber, a tribe of men Free would be joining.

The Indians called the 30-year-old chief of scouts “Sibber,” while the whites called the Apache scouts “Sieber’s Scouts” or “Sieber’s Apaches.” All were in awe of Sieber’s unflinching courage; he eventually bore 29 arrow or bullet scars on his body.

As he rode in astride his favorite white jennet, Sieber cut quite a figure. “A broad-brimmed, battered slouch hat was pulled well down over his brows; his flannel shirt and canvas trousers showed hard usage; his pistol belt hung loose and low upon his hips and on each side a revolver swung,” recalled 5th Cavalry Lt. Charles King. “His rifle—Arizona fashion—was balanced athwart the pommel of his saddle, and an old Navajo blanket was rolled at the cantle. He wore Tonto leggins and moccasins, and a good-sized pair of Mexican spurs jingled at his heels.”

Free, scrawny, disheveled, looking even younger than his 27 years, dressed like a White Mountain Apache. He could not yet match Sieber’s hard-bitten scout persona. In time, he would adopt considerable style, far more than Sieber ever sported.

That day marked the beginning of a remarkable partnership—one that would forever change the face of Apacheria. Some years later, when asked by Lt. Britton Davis about his enigmatic friend—who appeared to be neither white nor Apache—Sieber simply replied, with rough frontier affection, that Free was “half Mexican, half Irish and whole son of a bitch.”

Paul Andrew Hutton will be publishing a book tentatively titled The Lords of Apacheria, with Crown in New York City. He has published 10 books and teaches history at the University of New Mexico.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, December 10, 2010 –

– Courtesy Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, VintagePhoto.com –

– True West Archives –

– left courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection; right courtesy Marc Simmons –

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –