In 1849, the entire world seemed to be on the move to the California gold fields. One of the “Argonauts of ’49” was Vermonter William Manly. Like most of his fellow emigrants racing to the gold fields, Manly sought to reach California as quickly as possible and gather his fortune of gold, reputed to be lying around for the taking.

While traveling along the California Trail, Manly and friends concocted an outlandish scheme to float down the Green River to the Pacific Ocean.

When the crew reached Wyoming’s Green River in early August, the men found a gift from heaven—a 12-foot-long boat had been abandoned on a sandbar. So Manly, Richard Field, Charles Hazelrig, Joseph Hazelrig, M.S. McMahon, John Rogers and Alfred Walton decided to take the river route. They repaired and packed the boat for the adventure and, at Manly’s command, shoved off into the unknown.

At first, the river was gentle and slow, but as the party continued south, the currents increased. The men had a harder time using long poles to keep the boat from crashing into the increasingly frequent rocks. Manly was cast into the dangerous waters when his pole lodged between two rocks. He landed hard on his back, amazingly unharmed. He shook off the perilous experience and the rescue by his cheering crew as “nothing.”

At Ashley Falls, Manly and the crew were forced to unload the boat and attempt to pole the empty vessel past a large rock surrounded by swift swirling currents. The boat became inextricably stuck and had to be abandoned. The party fashioned canoes and then walked their boats and gear around the dangerous waterfalls.

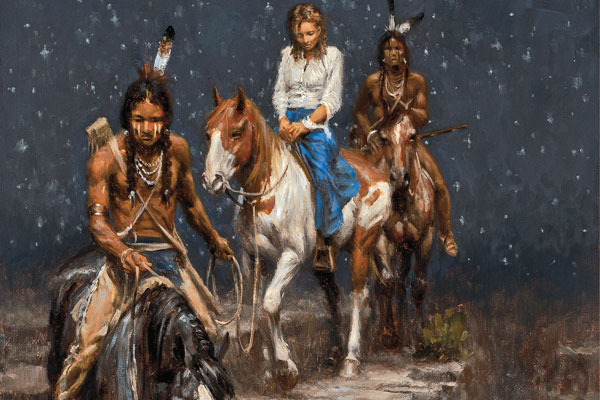

Continuing downriver in the unstable canoes tasked the travelers. A canoe flipped in rapids near Lodore, almost drowning Walton. In this mishap, most of the party’s weapons were lost in the turbulence.

The party continued by portaging around rapids. On September 12, after traveling an estimated 430 river miles, they met with Ute Chief Walkara, who strongly suggested their survival required them to abandon the river route and walk toward Utah’s Great Salt Lake City.

Field and McMahon did not heed the sage advice. They journeyed downriver and were forced to abandon their canoe in Desolation Canyon and walked overland to Wyoming. They eventually made it back to Salt Lake City, Utah, that winter.

Manly and the other four finished their 200-mile journey back to the emigrant trail. The Hazelrig brothers and Walton split from the group to travel the Mormon Trail. Manly and Rogers joined with the California-bound Jefferson Hunt Party, fated to become famous in Western lore as the emigrant party that gave “Death Valley” its name; but that is another story.

Survival Tip: How to Build a Canoe

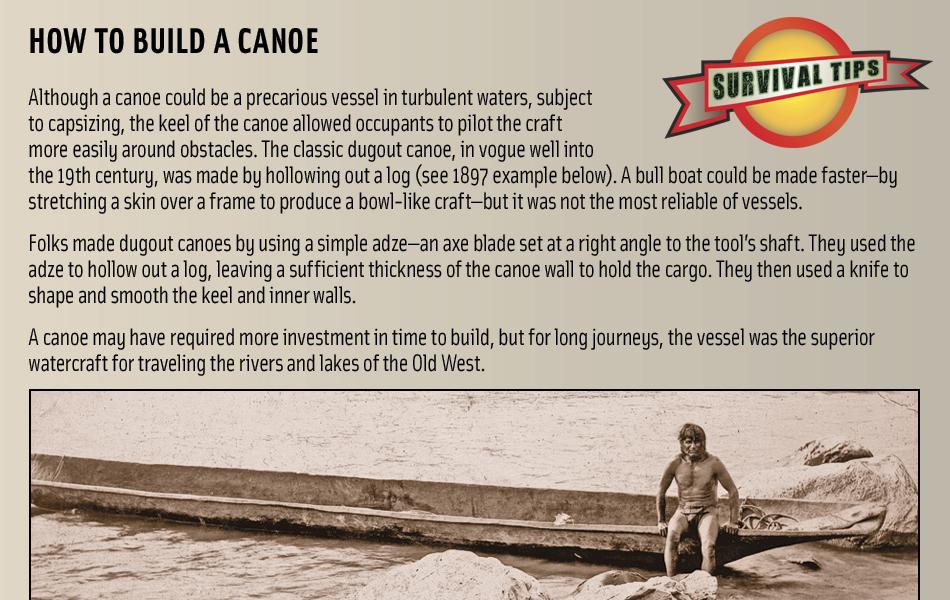

Although a canoe could be a precarious vessel in turbulent waters, subject to capsizing, the keel of the canoe allowed occupants to pilot the craft more easily around obstacles. The classic dugout canoe, in vogue well into the 19th century, was made by hollowing out a log (see 1897 example below). A bull boat could be made faster—by stretching a skin over a frame to produce a bowl-like craft—but it was not the most reliable of vessels. Folks made dugout canoes by using a simple adze—an axe blade set at a right angle to the tool’s shaft. They used the adze to hollow out a log, leaving a sufficient thickness of the canoe wall to hold the cargo. They then used a knife to shape and smooth the keel and inner walls. A canoe may have required more investment in time to build, but for long journeys, the vessel was the superior watercraft for traveling the rivers and lakes of the Old West. Although a canoe could be a precarious vessel in turbulent waters, subject to capsizing, the keel of the canoe allowed occupants to pilot the craft more easily around obstacles. The classic dugout canoe, in vogue well into the 19th century, was made by hollowing out a log (see 1897 example below). A bull boat could be made faster—by stretching a skin over a frame to produce a bowl-like craft—but it was not the most reliable of vessels. Folks made dugout canoes by using a simple adze—an axe blade set at a right angle to the tool’s shaft. They used the adze to hollow out a log, leaving a sufficient thickness of the canoe wall to hold the cargo. They then used a knife to shape and smooth the keel and inner walls. A canoe may have required more investment in time to build, but for long journeys, the vessel was the superior watercraft for traveling the rivers and lakes of the Old West.

History in Art

By Illustrator Andy Thomas

I painted the moment when the two smaller canoes flip, losing most weapons and nearly killing one man. In William Manly’s more detailed description, the swampings came from a fast straight section. My version implies they were in a cataract. The historical descriptions are vague, and it’s hard to say my painting isn’t right.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– True West archives –

I painted the moment when the two smaller canoes flip, losing most weapons and nearly killing one man. In William Manly’s more detailed description, the swampings came from a fast straight section. My version implies they were in a cataract. The historical descriptions are vague, and it’s hard to say my painting isn’t right.

– True West archives –